-40%

1949 Hebrew JEWISH WEDDING Israel BEZALEL Large ART BOOK Chagall RYBACK Judaica

$ 71.28

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

This is the ULIMATE GIFT for a JEWISH WEDDING !!!

Up for auction is an original Bezalel illustrated LEATHER IMMITATION covered Judaica LARGE JEWISH ART BOOK in HEBREW which was created around 75 years ago in 1949 in ERETZ ISRAEL by the BEZALEL SCHOOL of ART in JERUSALEM .

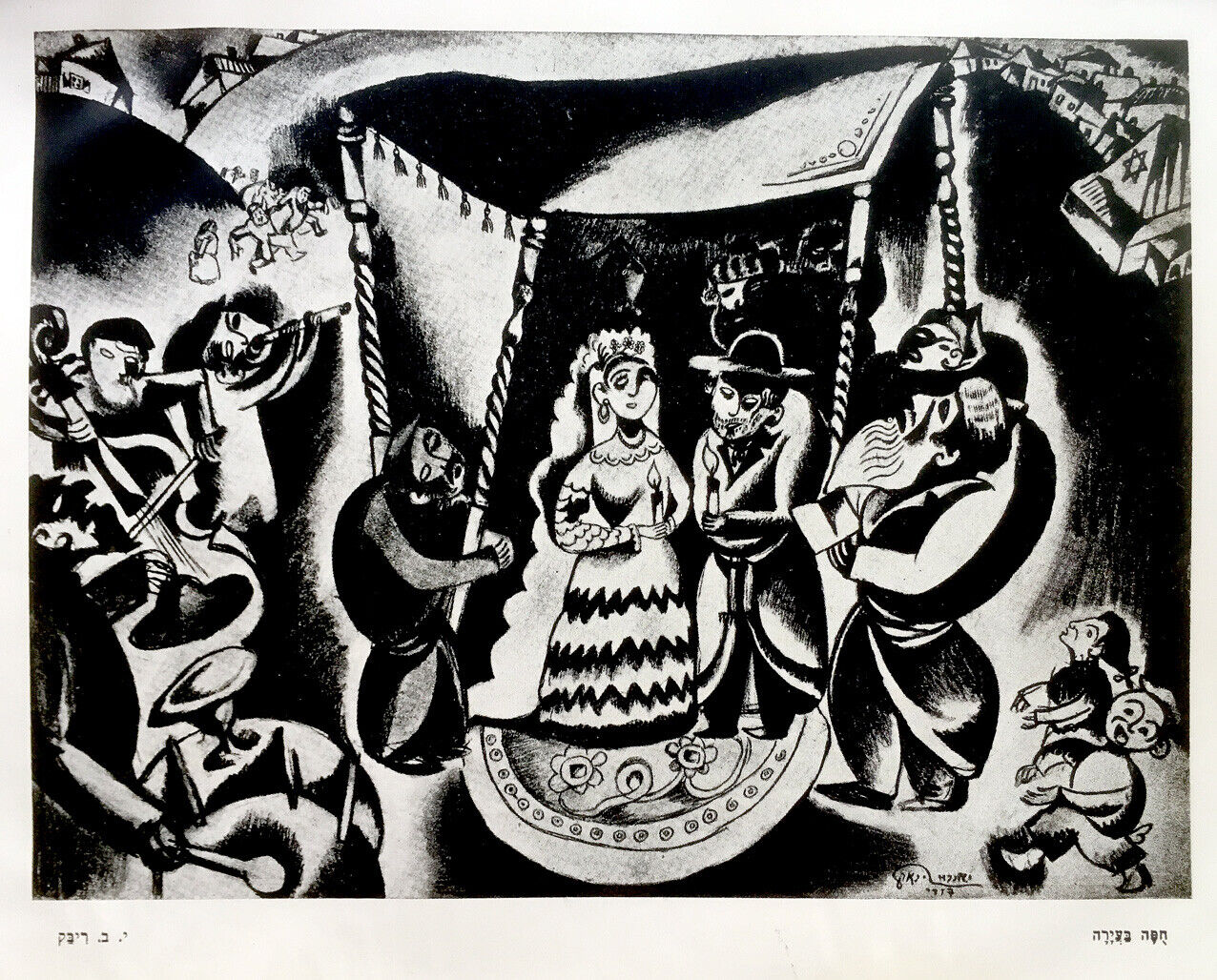

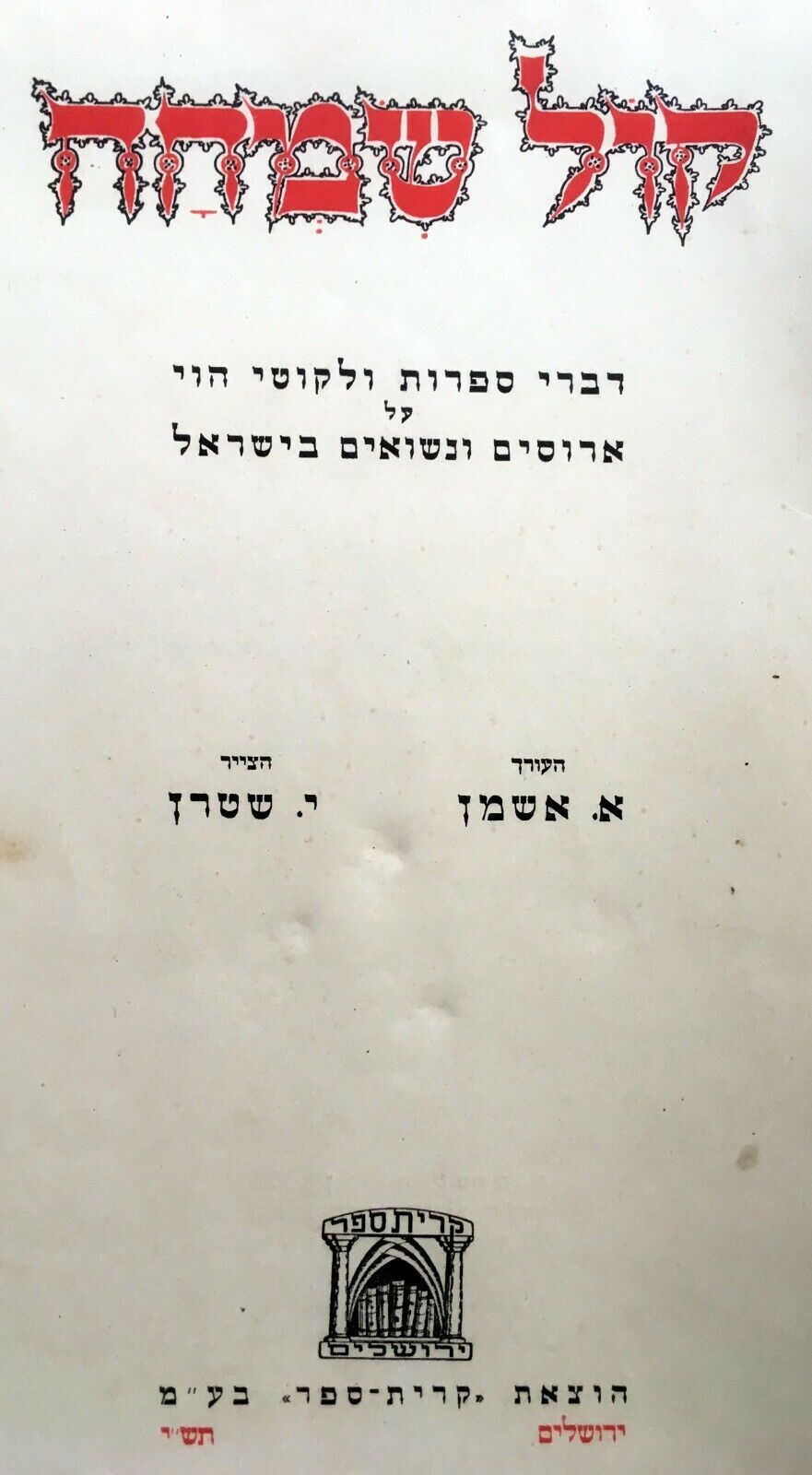

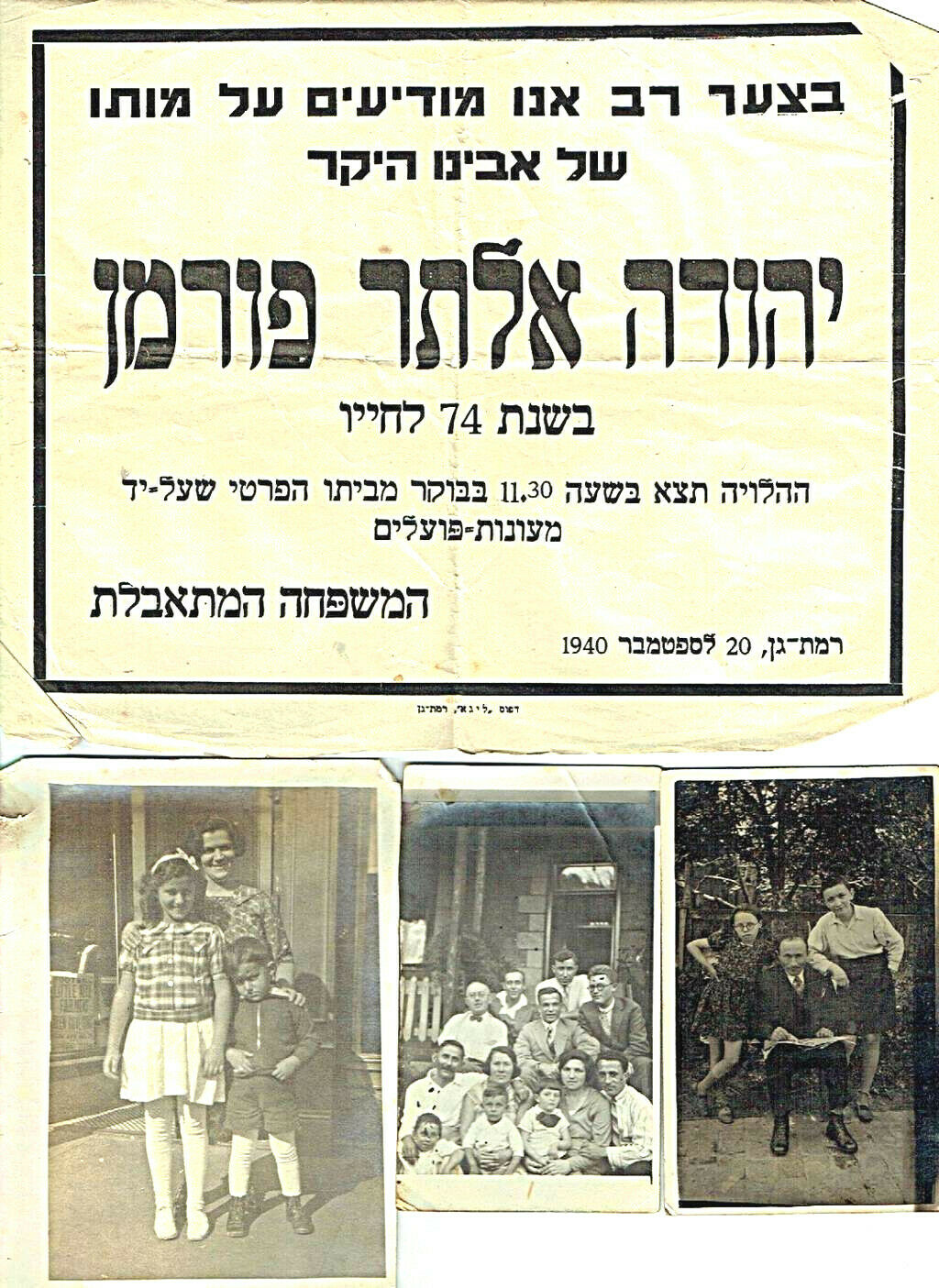

The piece was created in 1949 , Only one year after the establishment of the INDEPENDENT STATE of ISRAEL and its DECLARATION of INDEPENDENCE , While the WAR of INDEPENDENCE was still on. It's defined as "MEDINAT ISRAEL - The STATE of ISRAEL" , A typical definition to the first years after the establishment of the INDEPENDENT STATE of ISRAEL in 1948. The book "KOL SIMCHA" ( Kol Simcha being a Jewish WEDDING related expression ) is an ARTISTIC ANTHOLOGY of WEDDING RELATED stories, Poems, Songs, Legends which are accompanied by numerous wedding related JEWISH ART PIECES By Chagall , Ryback, Oppenheim , Gotlieb, Picart , Israels , Delacroix , Israeli Yossi Stern and others.

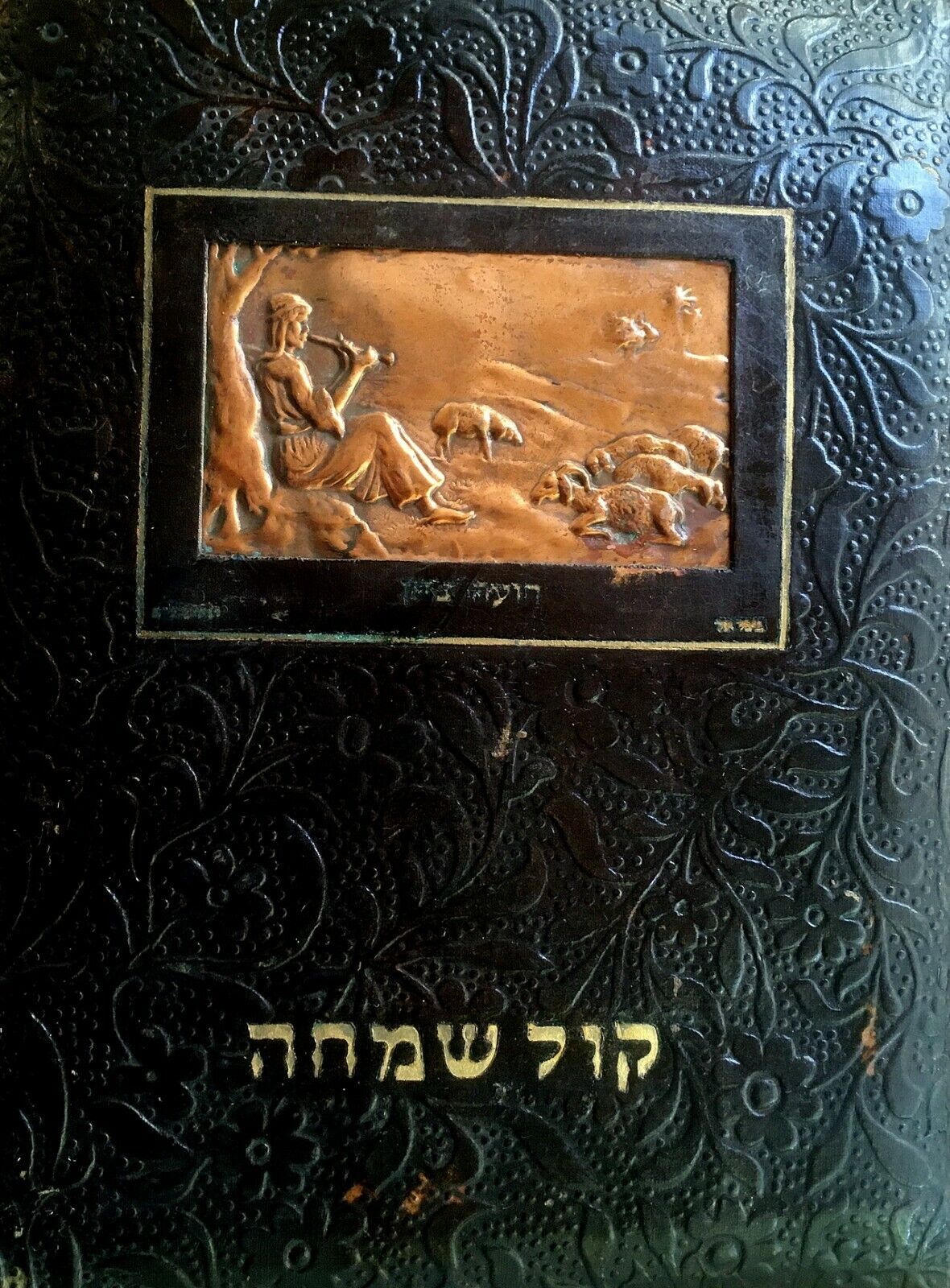

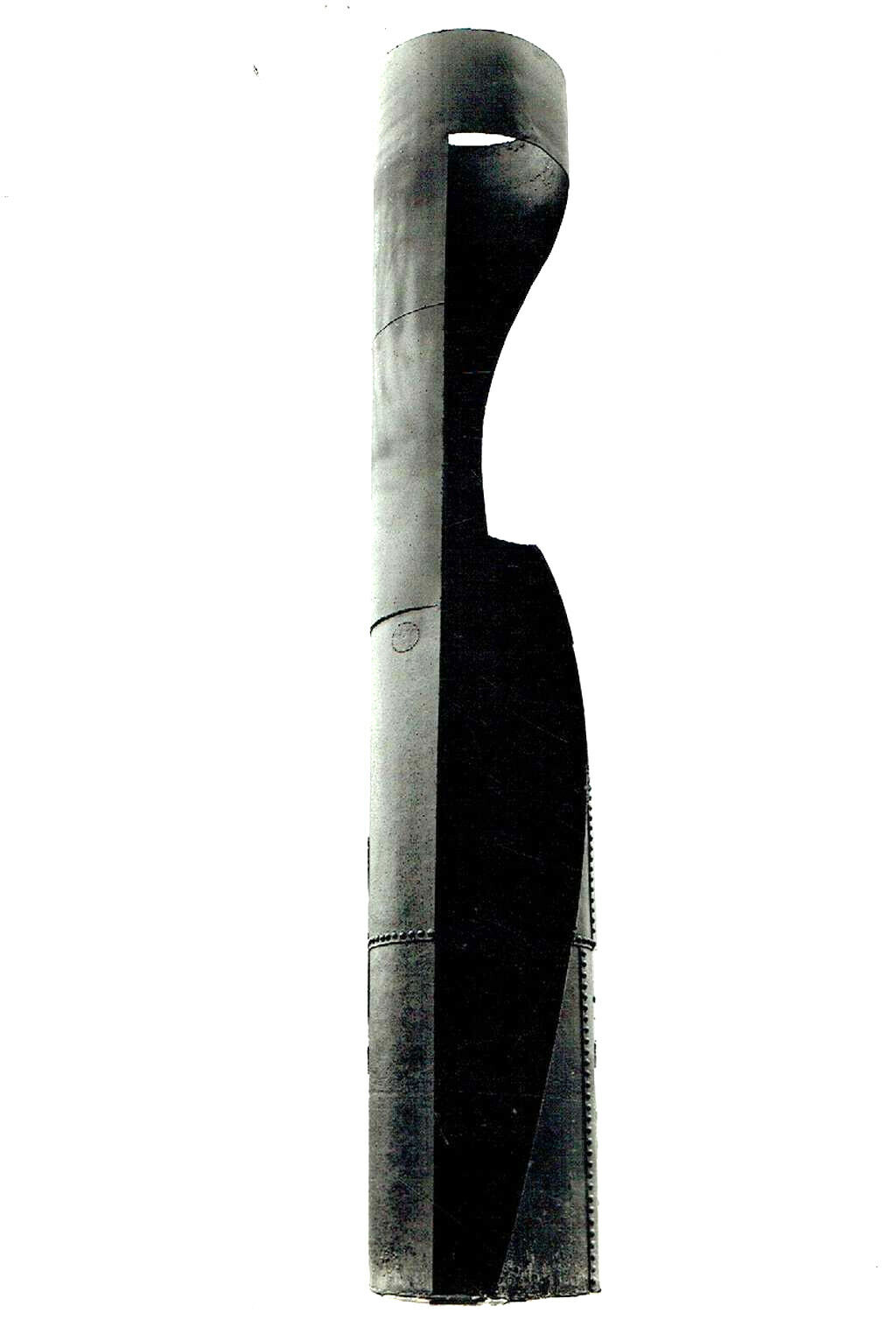

The strongly TOP MOUNTED leather immitation BOOK has a copper plaque - relief of ZEEV RABAN - The JEWISH BIBLICAL SHEPHERD playing his flute to his herd

.

The leather immitation cover with its STRONGLY MOUNTED TOP and FLOWERS DESIGNED PATTERN is a beauty . LARGE Size - a

round 12.5 x 9.5 ". 112 PP in B&W and RED . VERY GOOD CONDITION. The leather immitation binding is slightly worn but yet vivid and shiny . Tightly bound.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective packaging .

AUTHENTICITY

: This is an ORIGINAL vintage 1949

publication bound by ORIGINAL BEZALEL LEATHER IMMITATION binding created in ERETZ ISRAEL , NOT a reproduction , Immitation or a reprint , It holds a life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

: Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

: SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 35 ( Heavy volume ) .

Will be sent protected inside a protective rigid packaging

.

Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design is Israel's national school of art, founded in 1906 by Boris Schatz. It is named for the Biblical figure Bezalel, son of Uri (Hebrew: ), who was appointed by Moses to oversee the design and construction of the Tabernacle (Exodus 35:30). The Bezalel School was founded in 1906 by Boris Schatz. Theodor Herzl and the early Zionists believed in the creation of a national style of art blending classical Jewish/Middle Eastern and European traditions. The teachers of Bezalel developed a distinctive school of art, known as the Bezalel school, which portrayed Biblical and Zionist subjects in a style influenced by the European jugendstil (art nouveau) and traditional Persian and Syrian art. The artists blended

"varied strands of surroundings, tradition and innovation,"

in paintings and craft objects that invokes

"biblical themes, Islamic design and European traditions,"

in their effort to

"carve out a distinctive style of Jewish art"

for the new nation they intended to build in the ancient Jewish homeland.

The Bezalel School produced decorative art objects in a wide range of media: silver, leather, wood, brass and fabric. While the artists and designers were Western-trained, the craftsmen were often members of the Yemenite Jewish community, which has a long tradition of working in precious metals. Silver and goldsmithing had been traditional Jewish occupations in Yemen. Yemenite immigrants were also frequent subjects of Bezalel school artists. Leading artists of the school include Meir Gur Aryeh, Ze'ev Raban, Shmuel Ben David, Ya'ackov Ben-Dov, Ze'ev Ben-Tzvi, Jacob Eisenberg, Jacob Pins, Jacob Steinhardt, and Hermann Struck In 1912, the school had only one female student, Marousia (Miriam) Nissenholtz, who used the pseudonym Chad Gadya.The school closed down in 1929 in the wake of economic difficulties, but reopened in 1935, attracting many teachers and students from Germany, many of them from the Bauhaus school shut down by the Nazis.

A Jewish wedding is a wedding ceremony that follows Jewish laws and traditions. While wedding ceremonies vary, common features of a Jewish wedding include a ketubah (marriage contract) which is signed by two witnesses, a chuppah or huppah (wedding canopy), a ring owned by the groom that is given to the bride under the canopy, and the breaking of a glass. Technically, the Jewish wedding process has two distinct stages.[1] The first, kiddushin (Hebrew for "betrothal"; sanctification or dedication, also called erusin) and nissuin (marriage), is when the couple start their life together. This stage prohibits the woman to all other men, requiring a get (religious divorce) to dissolve it, while the second stage permits the couple to each other. The ceremony that accomplishes nissuin is also known as chuppah.[2] Today, erusin/kiddushin occurs when the groom gives the bride a ring or other object of value with the intent of creating a marriage. There are differing opinions as to which part of the ceremony constitutes nissuin/chuppah, such as standing under the canopy and being alone together in a room (yichud).[2] While historically these two events could take place as much as a year apart,[3] they are now commonly combined into one ceremony.[2] Contents 1 Signing of the marriage contract 2 Bridal canopy 3 Covering of the bride 4 Unterfirers 5 Circling 6 Presentation of the ring (Betrothal) 7 Seven blessings 8 Breaking the glass 9 Yichud 10 Special dances 11 Birkat hamazon and sheva brachot 12 Jewish prenuptial agreements 13 Timing 14 See also 15 References 16 External links Signing of the marriage contract[edit] Before the wedding ceremony, the groom agrees to be bound by the terms of the ketubah (marriage contract) in the presence of two witnesses, whereupon the witnesses sign the ketubah.[4] The ketubah details the obligations of the groom to the bride, among which are food, clothing, and marital relations. This document has the standing of a legally binding agreement, though it may be hard to collect these amounts in a secular court.[5] It is often written as an illuminated manuscript that is framed and displayed in their home.[6] Under the chuppah, it is traditional to read the signed ketubah aloud, usually in the Aramaic original, but sometimes in translation. Traditionally, this is done to separate the two basic parts of the wedding.[7] Non-Orthodox Jewish couples may opt for a bilingual ketubah, or for a shortened version to be read out. Bridal canopy[edit] A traditional Jewish wedding ceremony takes place under a chuppah (wedding canopy), symbolizing the new home being built by the couple when they become husband and wife.[8][9] Covering of the bride[edit] Jewish Wedding, Venice, 1780 Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme Prior to the ceremony, Ashkenazi Jews have a custom to cover the face of the bride (usually with a veil), and a prayer is often said for her based on the words spoken to Rebecca in Genesis 24:60.[10] The veiling ritual is known in Yiddish as badeken. Various reasons are given for the veil and the ceremony, a commonly accepted reason is that it reminds the Jewish people of how Jacob was tricked by Laban into marrying Leah before Rachel, as her face was covered by her veil (see Vayetze).[11] Another reasoning is that Rebecca is said to have veiled herself when approached by Isaac, who would become her husband.[12] Sephardi Jews do not perform this ceremony. Additionally, the veil emphasizes that the groom is not solely interested in the bride's external beauty, which fades with time; but rather in her inner beauty which she will never lose.[13] Unterfirers[edit] In many Orthodox Jewish communities, the bride is escorted to the chuppah by both mothers, and the groom is escorted by both fathers, known by Ashkenazi Jews as unterfirers (Yiddish: "Ones who lead under").[14] In another custom, bride and groom are each escorted by their respective parents.[15] However, the escorts may be any happily married couple, if parents are unavailable or undesired for some reason.[16] There is a custom in some Ashkenazi communities for the escorts to hold candles as they process to the chuppah.[17] Circling[edit] Plain gold wedding bands Outdoor Chuppah in Vienna, Austria A groom breaking the glass Dances at a Jewish wedding in Morocco, early 19th century 1893 painting of a marriage procession in a Russian shtetl by Isaak Asknaziy In Ashkenazi tradition, the bride traditionally walks around the groom three or seven times when she arrives at the chuppah. This may derive from Jeremiah 31:22, "A woman shall surround a man". The three circuits may represent the three virtues of marriage: righteousness, justice and loving kindness (see Hosea 2:19). Seven circuits derives from the Biblical concept that seven denotes perfection or completeness.[14] Sephardic Jews do not perform this ceremony.[18] Increasingly, it is common in liberal or progressive Jewish communities (especially Reform, Reconstructionist, or Humanistic) to modify this custom for the sake of egalitarianism, or for a same-gender couple.[19] One adaptation of this tradition is for the bride to circle the groom three times, then for the groom to circle his bride three times, and then for each to circle each other (as in a do-si-do).[20] The symbolism of the circling has been reinterpreted to signify the centrality of one spouse to the other, or to represent the four imahot (matriarchs) and three avot (patriarchs).[21] Presentation of the ring (Betrothal)[edit] See also: Erusin In traditional weddings, two blessings are recited before the betrothal; a blessing over wine, and the betrothal blessing, which is specified in the Talmud.[22] The wine is then tasted by the couple.[23] Rings are not actually required; they are simply the most common way (since the Middle Ages) of fulfilling the bride price requirement. The bride price (or ring) must have a monetary value no less than a single prutah (the smallest denomination of currency used during the Talmudic era). The low value is to ensure that there are no financial barriers to access marriage.[24] According to Jewish law, the ring must be composed of solid metal (gold or silver are preferred; alloys are discouraged), with no jewel inlays or gem settings, so that it's easy to ascertain the ring's value. Others ascribe a more symbolic meaning, saying that the ring represents the ideal of purity and honesty in a relationship. However, it's quite common for Jewish couples (especially those who are not Orthodox) to use weddings rings with engraving, metallic embellishments, or to go a step further and use gemstone settings. Some Orthodox couples will use a simple gold or silver band during the ceremony to fulfill the halachic obligations, and after the wedding, the bride may wear a ring with any decoration she likes.[25][26] The groom gives the bride a ring, traditionally a plain wedding band,[27] and recites the declaration: Behold, you are consecrated to me with this ring according to the law of Moses and Israel. The groom places the ring on the bride's right index finger. According to traditional Jewish law, two valid witnesses must see him place the ring.[23] During some egalitarian weddings, the bride will also present a ring to the groom,[28][29] often with a quote from the Song of Songs: "Ani l'dodi, ve dodi li" (I am my beloved's and my beloved is mine), which may also be inscribed on the ring itself.[30][31] This ring is sometimes presented outside the chuppah to avoid conflicts with Jewish law.[32][33][34] Seven blessings[edit] The Sheva Brachot or seven blessings are recited by the hazzan or rabbi, or by select guests who are called up individually. Being called upon to recite one of the seven blessings is considered an honour. The groom is given the cup of wine to drink from after the seven blessings. The bride also drinks the wine. In some traditions, the cup will be held to the lips of the groom by his new father-in-law and to the lips of the bride by her new mother-in-law.[35] Traditions vary as to whether additional songs are sung before the seven blessings. Breaking the glass[edit] After the bride has been given the ring, or at the end of the ceremony (depending on local custom), the groom breaks a glass, crushing it with his right foot. A lightbulb may be substituted at some contemporary weddings because it is thinner, more easily broken, and makes a louder popping sound.[36] Former Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel Ovadia Yosef has strongly criticized the way this custom is sometimes carried out, arguing that "Many unknowledgeable people fill their mouths with laughter during the breaking of the glass, shouting 'mazel tov' and turning a beautiful custom meant to express our sorrow" over Jerusalem's destruction "into an opportunity for lightheadedness."[37] The origin of this custom is unknown, although many reasons have been given. The primary reason is that joy must always be tempered.[38] This is based on two accounts in the Talmud of rabbis who, upon seeing that their son's wedding celebration was getting out of hand, broke a vessel – in the second case a glass – to calm things down.[39] Another explanation is that it is a reminder that despite the joy, Jews still mourn the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Because of this, some recite the verses "If I forget thee / O Jerusalem..." (Ps. 137:5) at this point.[27] Many other reasons have been given by traditional authorities.[38] Reform Judaism has a new custom where brides and grooms break the wine glass together.[citation needed] Yichud[edit] Yichud (togetherness or seclusion) refers to the Ashkenazi practice of leaving the bride and groom alone for 10–20 minutes after the wedding ceremony. The couple retreats to a private room. Yichud can take place anywhere, from a rabbi's study to a synagogue classroom.[40] The reason for yichud is that according to several authorities, standing under the canopy alone does not constitute chuppah, and seclusion is necessary to complete the wedding ceremony.[2] However, Sephardic Jews do not have this custom, as they consider it a davar mechoar (repugnant thing), compromising the couple's modesty.[41] In Yemen, the Jewish practice was not for the groom and his bride to be secluded in a canopy (chuppah), as is widely practiced today in Jewish weddings, but rather in a bridal chamber that was, in effect, a highly decorated room in the house of the groom. This room was traditionally decorated with large hanging sheets of colored, patterned cloth, replete with wall cushions and short-length mattresses for reclining.[42] Their marriage is consummated when they have been left together alone in this room. The chuppah is described the same way in Sefer HaIttur (12th century),[43] and similarly in the Jerusalem Talmud.[44] Special dances[edit] Dancing is a major feature of Jewish weddings. It is customary for the guests to dance in front of the seated couple and entertain them.[45] Traditional Ashkenazi dances include: The Krenzl, in which the bride's mother is crowned with a wreath of flowers as her daughters dance around her (traditionally at the wedding of the mother's last unwed daughter). The Mizinke, a dance for the parents of the bride or groom when their last child is wed. The Horah, a circle dance. Dancers link arms or hold hands, and move with a grapevine step. In large groups, concentric circles may be formed. The gladdening of the bride, in which guests dance around the bride, and can include the use of "shtick"—silly items such as signs, banners, costumes, confetti, and jump ropes made of table napkins. The Mitzvah tantz, in which family members and honored rabbis are invited to dance in front of the bride (or sometimes with the bride in the case of a father or grandfather), often holding a gartel, and then dancing with the groom. At the end the bride and groom dance together themselves. Birkat hamazon and sheva brachot[edit] After the meal, Birkat Hamazon (Grace after meals) is recited, followed by sheva brachot. At a wedding banquet, the wording of the blessings preceding Birkat Hamazon is slightly different from the everyday version.[46] Prayer booklets called bentshers may be handed out to guests. After the prayers, the blessing over the wine is recited, with two glasses of wine poured together into a third, symbolising the creation of a new life together.[45] Jewish prenuptial agreements[edit] In present times, Jewish rabbinical bodies have developed Jewish prenuptial agreements designed to prevent the husband from withholding a get from his wife, should she want a divorce. Such documents have been developed and widely used in the United States, Israel, the United Kingdom and other places. However, this approach has not been universally accepted, particularly by the Orthodox.[47] Conservative Judaism developed the Lieberman clause in order to prevent husbands from refusing to give their wives a get. To do this, the ketubah has built in provisions; so, if predetermined circumstances occur, the divorce goes into effect immediately.[48] Timing[edit] Weddings should not be performed on Shabbat or on Jewish holidays, including Chol HaMoed. The period of the counting of the omer and the three weeks are also prohibited, although customs vary regarding part of these periods. Some months and days are considered more or less auspicious.[49] ***** A chuppah (Hebrew: חוּפָּה, pl. חוּפּוֹת, chuppot, literally, "canopy" or "covering"), also huppah, chipe, chupah, or chuppa, is a canopy under which a Jewish couple stand during their wedding ceremony. It consists of a cloth or sheet, sometimes a tallit, stretched or supported over four poles, or sometimes manually held up by attendants to the ceremony. A chuppah symbolizes the home that the couple will build together. In a more general sense, chuppah refers to the method by which nesuin, the second stage of a Jewish marriage, is accomplished. According to some opinions, it is accomplished by the couple standing under the canopy along with the rabbi who weds them; however, there are other views.[1][2] Contents 1 Customs 2 History and legal aspects 3 Symbolism 4 Modern trends 5 See also 6 References 7 Further reading Customs[edit] Chuppa at a synagogue in Toronto, Canada A traditional chuppah, especially in Orthodox Judaism, recommends that there be open sky exactly above the chuppah,[3] although this is not mandatory among Sephardic communities. If the wedding ceremony is held indoors in a hall, sometimes a special opening is built to be opened during the ceremony. Many Hasidim prefer to conduct the entire ceremony outdoors. It is said that the couple's ancestors are present at the chuppah ceremony.[4] In Yemen, the Jewish practice was not for the groom and his bride to stand under a canopy (chuppah) hung on four poles, as is widely practised today in Jewish weddings, but rather to be secluded in a bridal chamber that was, in effect, a highly decorated room in the house of the groom, known as the chuppah[5] (see Yichud). History and legal aspects[edit] The word chuppah appears in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Joel 2:16; Psalms 19:5). Abraham P. Bloch states that the connection between the term chuppah and the wedding ceremony 'can be traced to the Bible'; however, 'the physical appearance of the chuppah and its religious significance have undergone many changes since then'.[6] There were for centuries regional differences in what constituted a 'huppah'. Indeed, Solomon Freehof finds that the wedding canopy was unknown before the 16th century.[7] Alfred J. Kolatch notes that it was during the Middle Ages that the 'chupa ... in use today' became customary.[8] Daniel Sperber notes that for many communities prior to the 16th century, the huppah consisted of a veil worn by the bride.[9] In others, it was a cloth spread over the shoulders of the bride and groom.[9] Numerous illustrations of Jewish weddings in medieval Europe, North Africa and Italy show no evidence of a huppah as it is known today. Moses Isserles (1520–1572) notes that the portable marriage canopy was widely adopted by Ashkenazi Jews (as a symbol of the chamber within which marriages originally took place) in the generation before he composed his commentary to the Shulchan Aruch.[9] In Biblical times, a couple consummated their marriage in a room or tent.[10] In Talmudic times, the room where the marriage was consummated was called the chuppah.[6] There is however a reference of a wedding canopy in the Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 57a: "It was the custom when a boy was born to plant a cedar tree and when a girl was born to plant a pine tree, and when they married, the tree was cut down and a canopy made of the branches". Jewish weddings consist of two separate parts: the betrothal ceremony, known as erusin or kiddushin, and the actual wedding ceremony, known as nisuin. The first ceremony (the betrothal, which is today accomplished when the groom gives a wedding ring to the bride) prohibits the bride to all other men and cannot be dissolved without a religious divorce (get). The second ceremony permits the bride to her husband. Originally, the two ceremonies usually took place separately.[1] After the initial betrothal, the bride lived with her parents until the day the actual marriage ceremony arrived; the wedding ceremony would then take place in a room or tent that the groom had set up for her. After the ceremony the bride and groom would spend an hour together in an ordinary room, and then the bride would enter the chuppah and, after gaining her permission, the groom would join her.[6] In the Middle Ages these two stages were increasingly combined into a single ceremony (which, from the 16th century, became the 'all but universal Jewish custom' and the chuppah lost its original meaning, with various other customs replacing it.[11] Indeed, in post-talmudic times the use of the chuppa chamber ceased;[6] the custom that became most common instead was to 'perform the whole combined ceremony under a canopy, to which the term chuppah was then applied, and to regard the bride's entry under the canopy as a symbol of the consummation of the marriage'.[11] The canopy 'created the semblance of a room'.[6] There are legal varying opinions as to how the chuppah ceremony is to be performed today. Major opinions include standing under the canopy, and secluding the couple together in a room (yichud).[1] The betrothal and chuppah ceremonies are separated by the reading of the ketubah.[12] This chuppah ceremony is connected to the seven blessings which are recited over a cup of wine at the conclusion of the ceremony (birchat nisuin or sheva brachot). Symbolism[edit] The chuppah represents a Jewish home symbolized by the cloth canopy and the four poles. Just as a chuppah is open on all four sides, so was the tent of Abraham open for hospitality. Thus, the chuppah represents hospitality to one's guests. This "home" initially lacks furniture as a reminder that the basis of a Jewish home is the people within it, not the possessions. In a spiritual sense, the covering of the chuppah represents the presence of God over the covenant of marriage. As the kippah served as a reminder of the Creator above all, (also a symbol of separation from God), so the chuppah was erected to signify that the ceremony and institution of marriage has divine origins.[citation needed] In Ashkenazic communities, before going under the chuppah the groom covers the bride's face with a veil, known as the badeken (in Yiddish) or hinuma (in Hebrew). The origin of this tradition and its original purpose are in dispute. There are opinions that the chuppah means "covering the bride's face", hence covering the couple to be married. Others suggest that the purpose was for others to witness the act of covering, formalizing the family's home in a community, as it is a public part of the wedding. In Sephardic communities, this custom is not practiced. Instead, underneath the chuppah, the couple is wrapped together underneath a tallit, which is a fringed garment. The groom enters the chuppah first to represent his ownership of the home on behalf of the couple. When the bride then enters the chuppah it is as though the groom is providing her with shelter or clothing, and he thus publicly demonstrates his new responsibilities toward her.[13] Modern trends[edit] A chuppah can be made of any material. A tallit or embroidered velvet cloth are commonly used. Silk or quilted chuppot are increasingly common, and can often be customized or personalized to suit the couple's unique interests and occupations.[14][15] ***[21][note 2]

ebay5572 folder 122