-40%

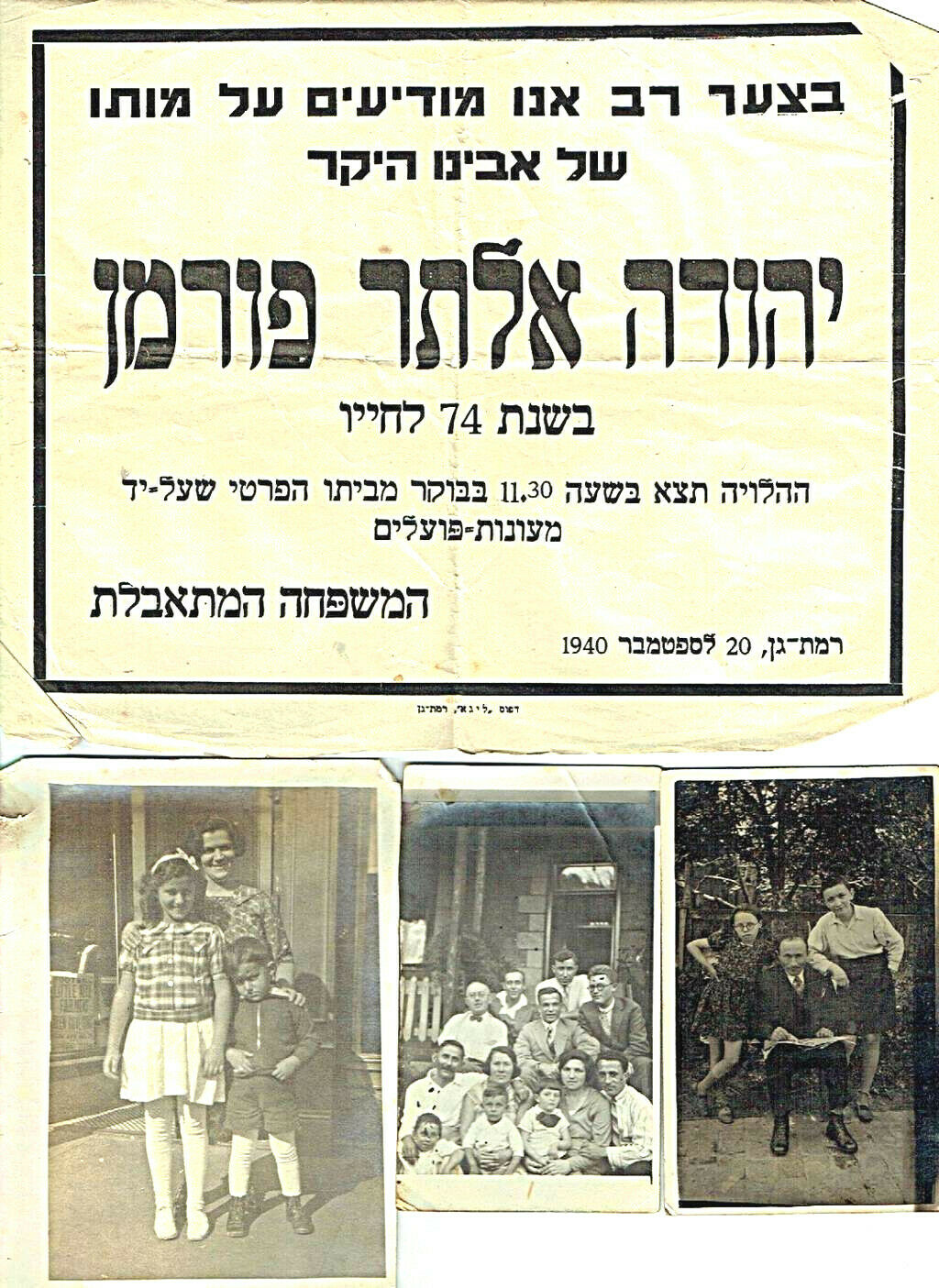

1960 Hebrew RARE ADVERTISING LABEL Israel BEIGEL TOAST Bagel KOSHER Bread JEWISH

$ 19.56

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

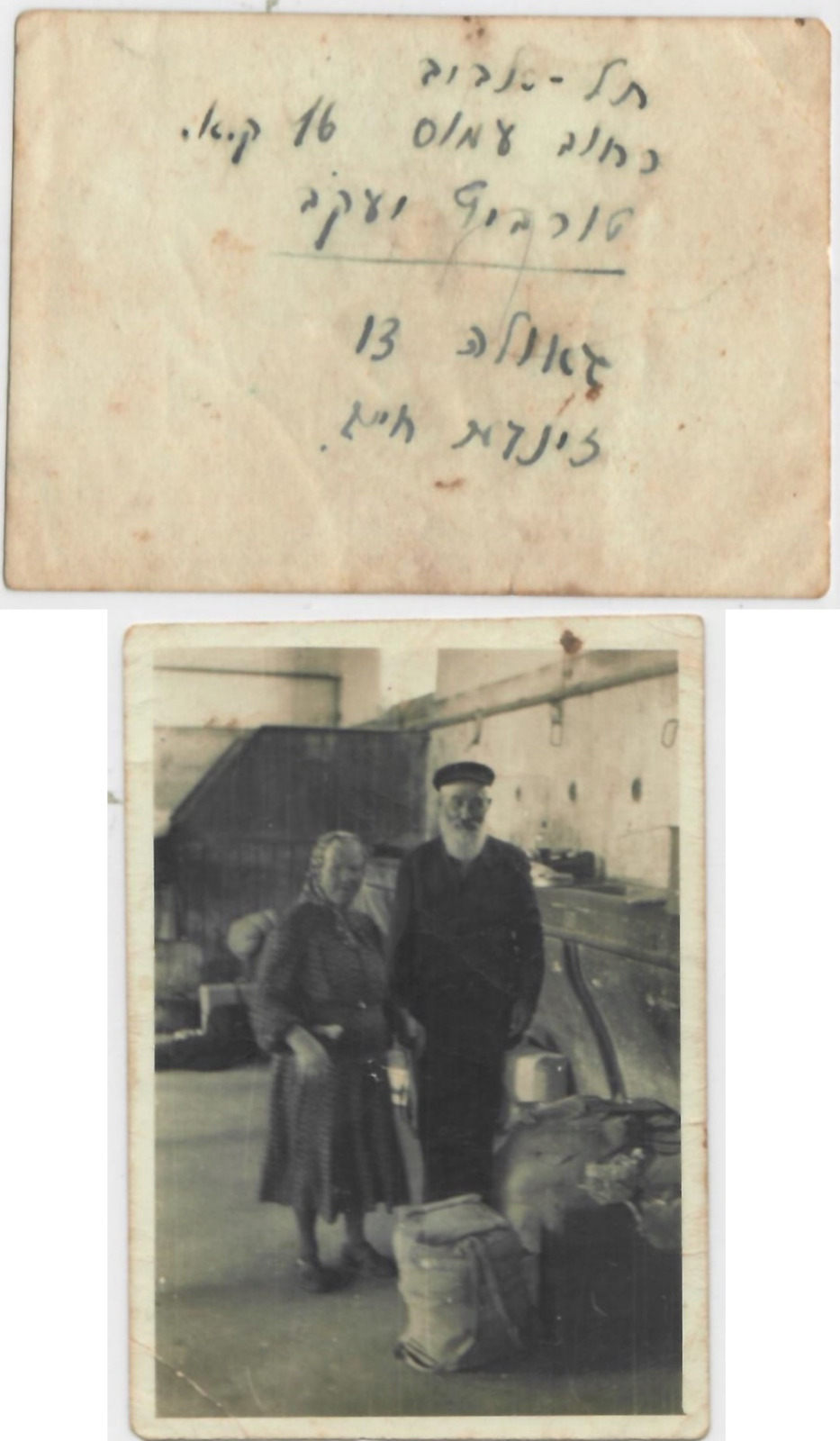

Up for auction is an original vintage small size advertising Jewish LABEL -POSTER for a KOSHER MADE IN ISRAEL product , Namely FINEST BEIGEL TOAST of the manufactor "BEIGEL" , A firm which is long ago vanished. The LABEL for the KOSHER PRODUCT was used in the 1950's up to the 1960's in HAIFA Israel. The LABEL - POSTER advertises the product " KAMA ( Standing Grain ) " . Related to cook - cooking. Thick cardboard. Dimensions are around 4.5 x 3.5". Very g

ood condition.

thick cardboard

.

( Please look at scan for an accurate AS IS image) .

Will be sent inside a protective rigid package.

AUTHENTICITY

:

This is an ORIGINAL vintage ca 1950's - 1960's ISRAEL label , NOT a reproduction or a reprint , It holds a life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

:

SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 19 . Will be sent inside a protective rigid package

.

Handling around 5 days after payment.

A bagel (Yiddish: בײגל baygl; Polish: bajgiel), also spelled beigel,[1] is a bread product originating in the Jewish communities of Poland. It is traditionally shaped by hand into the form of a ring from yeasted wheat dough, roughly hand-sized, that is first boiled for a short time in water and then baked. The result is a dense, chewy, doughy interior with a browned and sometimes crisp exterior. Bagels are often topped with seeds baked on the outer crust, with the traditional ones being poppy or sesame seeds. Some may have salt sprinkled on their surface, and there are different dough types, such as whole-grain or rye.[2][3] Though the origins of bagels are somewhat obscure, it is known that they were widely consumed in Ashkenazi Jewishcommunities from the 17th century. The first known mention of the bagel, in 1610, was in Jewish community ordinances in Kraków, Poland. Bagels are now a popular bread product in North America, especially in cities with a large Jewish population, many with alternative ways of making them. Like other bakery products, bagels are available (fresh or frozen, often in many flavors) in many major supermarkets in those countries. The basic roll-with-a-hole design is hundreds of years old and has other practical advantages besides providing more even cooking and baking of the dough: The hole could be used to thread string or dowels through groups of bagels, allowing easier handling and transportation and more appealing seller displays.[4][5] Contents [hide] 1 History 2 Preparation and preservation 3 Quality 4 Varieties 5 Non-traditional doughs and types 6 Large scale commercial sales 6.1 United States supermarket sales 6.1.1 2008 6.1.2 2012 7 Similar breads 8 Cultural references 9 See also 10 References 10.1 Citations 10.2 Bibliography 11 External links History[edit] Linguist Leo Rosten wrote in The Joys of Yiddish about the first known mention of the Polish word bajgiel derived from the Yiddish word bagel in the "Community Regulations" of the city of Kraków in 1610, which stated that the item was given as a gift to women in childbirth.[6] In the 16th and first half of the 17th centuries, the bajgiel became a staple of Polish cuisine[7] and a staple of the Slavic diet generally.[8] Its name derives from the Yiddish word beygal from the German dialect word beugel, meaning "ring" or "bracelet".[9] Variants of the word beugal are used in Yiddish and in Austrian German to refer to a similar form of sweet-filled pastry (Mohnbeugel (with poppy seeds) and Nussbeugel (with ground nuts), or in southern German dialects (where beuge refers to a pile, e.g., holzbeuge "woodpile"). According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, 'bagel' derives from the transliteration of the Yiddish 'beygl', which came from the Middle High German 'böugel' or ring, which itself came from 'bouc' (ring) in Old High German, similar to the Old English bēag "ring" and būgan "to bend, bow".[10] Similarly, another etymology in the Webster's New World College Dictionary says that the Middle High German form was derived from the Austrian German beugel, a kind of croissant, and was similar to the German bügel, a stirrup or ring.[11] In the Brick Lane district and surrounding area of London, England, bagels (locally spelled "beigels") have been sold since the middle of the 19th century. They were often displayed in the windows of bakeries on vertical wooden dowels, up to a metre in length, on racks. Bagels with cream cheese and lox (cured salmon) are considered a traditional part of American Jewish cuisine (colloquially known as "lox and a schmear"). Bagels were brought to the United States by immigrant Polish Jews, with a thriving business developing in New York Citythat was controlled for decades by Bagel Bakers Local 338. They had contracts with nearly all bagel bakeries in and around the city for its workers, who prepared all their bagels by hand. The bagel came into more general use throughout North America in the last quarter of the 20th century with automation. Daniel Thompson started work on the first commercially viable bagel machine in 1958; bagel baker Harry Lender, his son, Murray Lender, and Florence Sender leased this technology and pioneered automated production and distribution of frozen bagels in the 1960s.[12][13][14] Murray also invented pre-slicing the bagel.[15] Around 1900, the "bagel brunch" became popular in New York City.[16] The bagel brunch consists of a bagel topped with lox, cream cheese, capers, tomato, and red onion.[16] This and similar combinations of toppings have remained associated with bagels into the 21st century in the US.[17][18][19] In Japan, the first kosher bagels were brought by BagelK (ja) from New York in 1989. BagelK created green tea, chocolate, maple-nut, and banana-nut flavors for the market in Japan. There are three million bagels exported from the U.S. annually, and it has a 4%-of-duty classification of Japan in 2000. Some Japanese bagels, such as those sold by BAGEL & BAGEL (ja), are soft and sweet; others, such as Einstein Bro. bagels sold by Costco in Japan, are the same as in the U.S. Preparation and preservation[edit] Saturday morning bagel queue at St-Viateur Bagel, Montreal, Quebec At its most basic, traditional bagel dough contains wheat flour (without germ or bran), salt, water, and yeast leavening. Bread flour or other high gluten flours are preferred to create the firm, dense but spongy bagel shape and chewy texture.[2] Most bagel recipes call for the addition of a sweetener to the dough, often barley malt (syrup or crystals), honey, high fructose corn syrup, sugar, with or without eggs, milk or butter.[2] Leavening can be accomplished using a sourdough technique or a commercially produced yeast. Bagels are traditionally made by: mixing and kneading the ingredients to form the dough shaping the dough into the traditional bagel shape, round with a hole in the middle, from a long thin piece of dough proofing the bagels for at least 12 hours at low temperature (40–50 °F = 4.5–10 °C) boiling each bagel in water that may contain additives such as lye, baking soda, barley malt syrup, or honey baking at between 175 °C and 315 °C (about 350–600 °F) This production method gives bagels their distinctive taste, chewy texture, and shiny appearance. In recent years, a variant has emerged, producing what is sometimes called the steam bagel. To make a steam bagel, the boiling is skipped, and the bagels are instead baked in an oven equipped with a steam injection system.[20] In commercial bagel production, the steam bagel process requires less labor, since bagels need only be directly handled once, at the shaping stage. Thereafter, the bagels need never be removed from their pans as they are refrigerated and then steam-baked. The steam bagel results in a fluffier, softer, less chewy product more akin to a finger roll that happens to be shaped like a bagel. Steam bagels are considered lower quality by purists as the dough used is intentionally more alkaline.[citation needed] The increase in pH is to aid browning, since the steam injection process uses neutral water steam instead of an alkaline solution bath. Bagels can be frozen for up to six months.[21] Quality[edit] According to a 2012 Consumer Reports article, the ideal bagel should have a slightly crispy crust, a distinct "pull" when a piece is separated from the whole by biting or pinching, a chewy inside, and the flavor of bread freshly baked. The taste may be complemented by additions cooked on the bagel, such as onion, garlic, sesame seeds, or poppy seeds. The appeal of a bagel may change upon being toasted. Toasting can have the effect of bringing or removing desirable chewiness, softening the crust, and moderating off-flavors.[22] A typical bagel has 260–350 calories, 1.0–4.5 grams of fat, 330–660 milligrams of sodium, and 2–5 grams of fiber. Gluten-free bagels have much more fat, often 9 grams, because of the presence in the dough of ingredients that supplant wheat flour in the original.[22] Varieties[edit] See also: Montreal-style bagel Three Montreal-style bagels: one poppyand two sesame bagels Traditional bagels in North America can be either Montreal-style bagel or New York-style,[23] although both styles reflect traditional methods used in Eastern Europe before bagels' importation to North America. The distinction is less rigid than often maintained. The Montreal-style bagel contains malt and sugar with no salt; it is boiled in honey-sweetened water before baking in a wood-fired oven. It is predominantly of the sesame "white" seeds variety (bagels in Toronto are similar to those made in New York in that they are less sweet, generally are coated with poppy seeds and are baked in a standard oven). In contrast, the New York bagel contains salt and malt and is boiled in water before baking in a standard oven. The resulting bagel is puffy with a moist crust. The Montreal bagel is smaller (though with a larger hole), crunchier, and sweeter.[24] There is a belief that New York bagels are the best due to the quality of the local water.[25] However, this belief is heavily debated. For instance, Davidovich Bagels, made in NYC, are a recognized wholesale manufacturer of bagels that use these traditional bagel-making techniques (associated here with the Montreal-style bagel), including kettle boiling and plank baking in a wood fired oven.[26] As suggested above, other bagel styles can be found elsewhere, akin to the way in which families in a given culture employ a variety of methods when cooking an indigenous dish. Thus, Chicago-style bagels are baked or baked with steam.[27] The traditional London bagel (or beigel as it is spelled) is harder and has a coarser texture with air bubbles. Poppy seeds are sometimes referred to by their Yiddish name, spelled either mun or mon (written מאָן), which comes from the German word for poppy, Mohn, as used in Mohnbrötchen. American chef John Mitzewich suggests a recipe for what he calls “San Francisco-Style Bagels”. His recipe yields bagels flatter than New York-style bagels, characterized by a rough-textured crust.[28] An everything bagel may include such toppings as poppy seeds, sesame seeds, onion flakes, caraway seeds, garlic flakes, pretzel salt, and pepper. Non-traditional doughs and types[edit] While normally and traditionally made of yeasted wheat, in the late 20th century variations on the bagel flourished. Non-traditional versions that change the dough recipe include pumpernickel, rye, sourdough, bran, whole wheat, and multigrain. Other variations change the flavor of the dough, often using blueberry, salt, onion, garlic, egg, cinnamon, raisin, chocolate chip, cheese, or some combination of the above. Green bagels are sometimes created for St. Patrick's Day. Many corporate chains now offer bagels in such flavors as chocolate chip and French toast. Sandwich bagels have been popularized since the late 1990s by specialty shops such as Bruegger's and Einstein Brothers, and fast food restaurants such as McDonald's. Breakfast bagels, a softer, sweeter variety usually sold in fruity or sweet flavors (e.g., cherry, strawberry, cheese, blueberry, cinnamon-raisin, chocolate chip, maple syrup, banana and nuts) are common at large supermarket chains. These are usually sold sliced and are intended to be prepared in a toaster. A flat bagel, known as a 'flagel', can be found in a few locations in and around New York City, Long Island, and Toronto. According to a review attributed to New York's Village Voice food critic Robert Seitsema, the flagel was first created by Brooklyn's 'Tasty Bagels' deli in the early 1990s.[29] The New York Style Snacks brand has developed the baked snacks referred to as Bagel Crisps and Bagel Chips, which are marketed as a representation of the "authentic taste" of New York City bakery bagels.[30] Though the original bagel has a fairly well-defined recipe and method of production, there is no legal standard of identity for bagels in the United States. Bakers are free to call any bread torus a bagel, even those that deviate wildly from the original formulation. Toast is sliced bread that has been browned by exposure to radiant heat. This browning is the result of a Maillard reaction altering the flavor of the bread and making it firmer so that it is easier to spread toppings on it. Toasting is a common method of making stale bread more palatable. Bread is often toasted using a toaster, but toaster ovens are also used. Though many types of bread can be toasted the most commonly used is "toast bread", referring to bread that is already sliced and bagged upon purchase and may be white, brown, or multigrain. Toast is commonly eaten with butter or margarine and sweetened toppings, such as jam or jelly. Regionally, savoury spreads, such as peanut butter or yeast extracts, may also be popular. When buttered, toast may also be served as an accompaniment to savoury dishes, especially soups or stews, or topped with heartier ingredients like eggs or baked beans as a light meal. Toast is a common breakfast food. While slices of bread are most common, bagels and English muffins are also toasted. Scientific studies in the early 2000s found that toast may contain carcinogens caused by the browning process.[1][2] Contents [hide] 1 Etymology and history 2 Preparation 3 Consumption 4 Health concerns 5 Cultural references 6 Other foods which are toasted 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Etymology and history[edit] The word "toast", which means "sliced bread singed by heat" comes from the Latin torrere, "to burn".[3] The first reference to toast in print is in a recipe for Oyle Soppys (flavoured onions stewed in a gallon of stale beer and a pint of oil) that dates from 1430.[4] In the 1400s and 1500s, toast was discarded or eaten after it was used as a flavouring for drinks.[4] In the 1600s, toast was still thought of as something that was "put it into drinks. Shakespeare gave this line to Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor, 1616: "Go, fetch me a quart of Sacke [sherry], put a tost in 't."[4] By the 1700s, there were references to "toast" as a gesture that indicates sexual attraction for a person: "Ay, Madam, it has been your Life's whole Pride of late to be the Common Toast of every Publick Table."[4] Toast has been used as an element of American haute cuisine since at least the 1850s.[5] Preparation[edit] A classic two-slot toaster In a modern home kitchen, the usual method of toasting bread is by the use of a toaster, an electrical appliance made for that purpose. To use a modern toaster, sliced bread is placed into the narrow slots on the top of the toaster, the toaster is tuned to the correct setting (some may have more elaborate settings than others) and a lever on the front or side is pushed down. The toast is ready when the lever pops up along with the toast. If the bread is insufficiently toasted, the lever can be pressed down again. Bread toasted in a conventional toaster can "sweat" when it is served (i.e. water collects on the surface of the cooled toast). This occurs because moisture in the bread becomes steam while being toasted due to heat and when cooled the steam condenses into water droplets on the surface of the bread.[6] It can also be toasted by a conveyor toaster which are often used in hotels, restaurants and other food service locations. These work by having one heating element on the top and one on the bottom with a metal conveyor belt in the middle which carries the toast between the two heating elements. This allows toast to be made consistently as more slices can be added at any time without waiting for previous ones to pop up. Bread can also be toasted under a grill (or broiler), in an open oven, or lying on an oven rack. This "oven toast" is usually buttered before toasting. Toaster ovens are special small appliances made for toasting bread or for heating small amounts of other foods. Bread can also be toasted by holding it near but not directly over an open flame, such as a campfire or fireplace; special toasting utensils (e.g. toasting forks) are made for this purpose. Before the invention of modern cooking appliances such as toasters and grills, bread has been produced in ovens for millennia, toast can be made in the same oven. Many brands of ready sliced bread are available, some specifically marketing their suitability for toasting. Consumption[edit] Left: Toast with butter and vegemite. Right: With butter and strawberry jelly. Toast is most commonly eaten with butter or margarine spread over it, and may be served with preserves, spreads, or other toppings in addition to or instead of butter. Toast with jam or marmalade is popular. A few other condiments that can be enjoyed with toast are chocolate spread, cream cheese, and peanut butter. Yeast extracts such as Marmite in the UK, New Zealand and South Africa, and Vegemite in Australia are national traditions. Some sandwiches, such as the BLT,[7] call for toast to be used rather than bread. Toast is an important component of many breakfasts, and is also important in some traditional bland specialty diets for people with gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea. In the United Kingdom, a dish popular with children is a soft-boiled egg eaten with toast soldiers at breakfast. Strips of toast (the soldiers) are dipped into the runny yolk of a boiled egg through a hole made in the top of the eggshell, and eaten.[8] In southern Sri Lanka it is common for toast to be paired with a curry soup and mint tea. By 2013 "artisanal toast" had become a significant food trend in upscale American cities like San Francisco, where some commentators decried the increasing number of restaurants and bakeries selling freshly made toast at what was perceived to be an unreasonably high price.[9][10] Health concerns[edit] Toasted bread slices may contain Benzo[a]pyrene and high levels of acrylamide, a carcinogen generated during the browning process.[1] High acrylamide levels can also be found in other heated carbohydrate-rich foods.[2] The darker the surface colour of the toast, the higher its concentration of acrylamide.[1] That is why, according to the recommendations made by the British Food Standards Agency, bread should be toasted to the lightest colour acceptable.[11] Cultural references[edit] The slang idiom "you're toast", "I'm toast" or "we're toast" is used to express a state of being "outcast", "finished", "burned, scorched, wiped out, [or] demolished" (without even the consolation of being remembered, as with the slang term "you're history")."[3] The first known use of "toast" as a metaphorical term for "you're dead" was in the 1984 film Ghostbusters, in which Bill Murray's character declares "This chick is toast" before the Ghostbusters attempt to burn the villain with their nuclear-powered weapons.[4] "Hey, dude. You're toast, man", which appeared in The St. Petersburg Times of Oct. 1, 1987, is the "...earliest [printed] citation the Oxford English Dictionary research staff has of this usage."[3] Another popular idiom associated with the word "toast" is the expression "to toast someone's health", which is typically done by one or more persons at a gathering by raising a glass in salute to the individual. This meaning is derived from the early meaning of toast, which from the 1400s to the 1600s meant warmed bread that was placed in a drink. By the 1700s, there were references to the drink in which toast was dunked being used in a gesture that indicates respect: "Ay, Madam, it has been your Life's whole Pride of late to be the Common Toast of every Public Table."[4][better source needed] Humorous observations have been made about buttered toast. It has been noted that buttered toast has a perceived tendency, when dropped, to land with the buttered side to the floor, the least desirable outcome. Although the concept of "dropped buttered toast" was originally a pessimistic joke, a 2001 study of the buttered toast phenomenon found that when dropped from a table, a buttered slice of toast landed butter-side down at least 62% of the time.[12] The phenomenon is widely believed to be attributable to the combination of the size of the toast and the height of the typical dining table, which means that the toast will not rotate far enough to right itself before encountering the floor.[13][14] A joke that plays on this tendency is the buttered cat paradox; if cats always land on their feet and buttered toast always lands buttered side down, it questions what happens when buttered toast is attached to a cat's back. Kashrut (also kashruth or kashrus, כַּשְׁרוּת) is a set of Jewish religious dietary laws. Food that may be consumed according to halakha (Jewish law) is termed kosher (/ˈkoʊʃər/ in English, Yiddish: כּשר), from the Ashkenazipronunciation of the Hebrew term kashér (כָּשֵׁר), meaning "fit" (in this context, fit for consumption). Among the numerous laws that form part of kashrut are the prohibitions on the consumption of certain animals (such as pork, shellfish [both Mollusca and Crustacea], and most insects, with the exception of certain species of kosher locusts), mixtures of meat and milk, and the commandment to slaughter mammals and birds according to a process known as shechita. There are also laws regarding agricultural produce that might impact the suitability of food for consumption. Most of the basic laws of kashrut are derived from the Torah's Books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy. Their details and practical application, however, are set down in the oral law (eventually codified in the Mishnah and Talmud) and elaborated on in the later rabbinical literature. Although the Torah does not state the rationale for most kashrut laws, some suggest that they are only tests for man's obedience,[1] while others have suggested philosophical, practical and hygienic reasons.[2] Over the past century, many rabbinical organizations have started to certify products, manufacturers, and restaurants as kosher, usually using a symbol (called a hechsher) to indicate their support. Currently, about a sixth of American Jews or 0.3% of the American population fully keep kosher, and there are many more who do not strictly follow all the rules but still abstain from some prohibited foods (especially pork). ebay4365