-40%

1961 Israel HAND SIGNED ART PAINTING Jewish MIXED MEDIA Moshe GIVATI Hebrew

$ 71.28

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

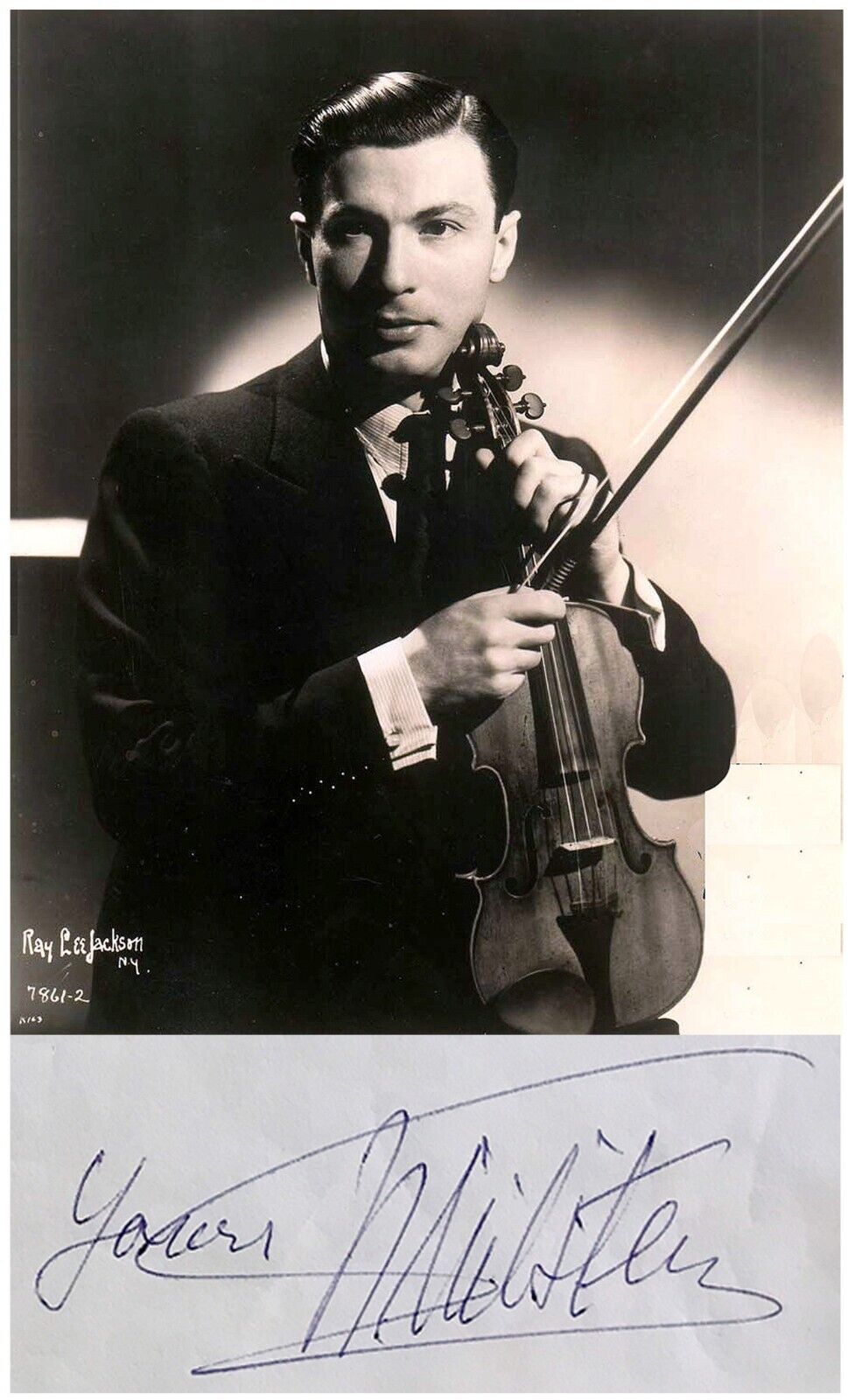

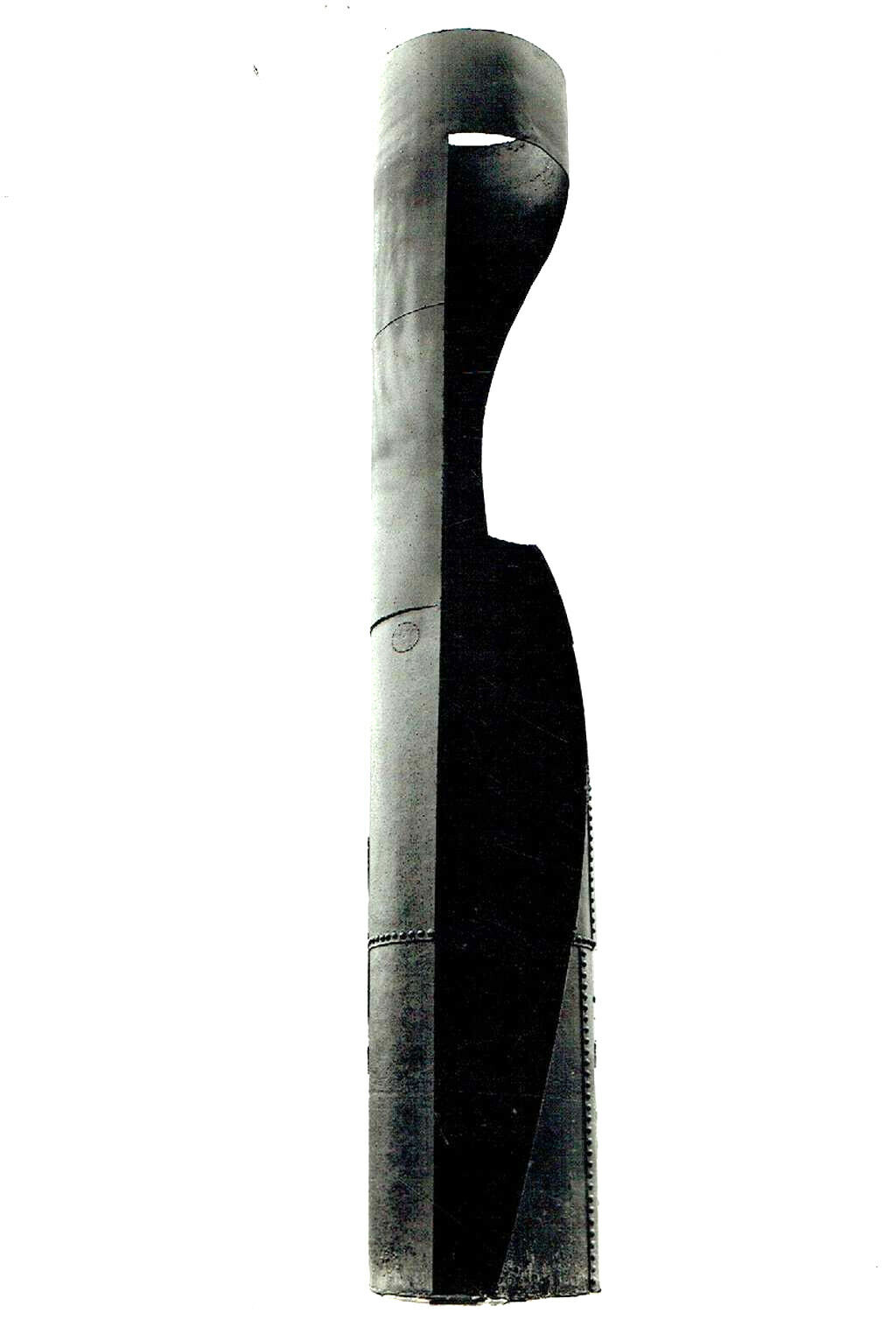

Up for auction is an ORIGINAL hand SIGNED Israeli MIXED MEDIA ART PIECE

by the acclaimed Israeli artist , The most admired painter MOSHE GIVATI . Depicting a quite figurative scene of THREE HUMAN FIGURES. Hand SIGNED and DATED with green pen by the artist in Hebrew "M.GIVATI 61".

size is around 10

x 9 " . Very good condition.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )

. The piece will be sent in a special protective rigid sealed packaging.

AUTHENTICITY

: This is an ORIGINAL vintage 1961 hand signed MIXED MEDIA ART PIECE , NOT a reproduction or a reprint , It holds life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

: P

ayment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 19 .

Will be sent in a special protective rigid sealed packaging.

Handling within 3-5 days after payment. Estimated duration 14 days.

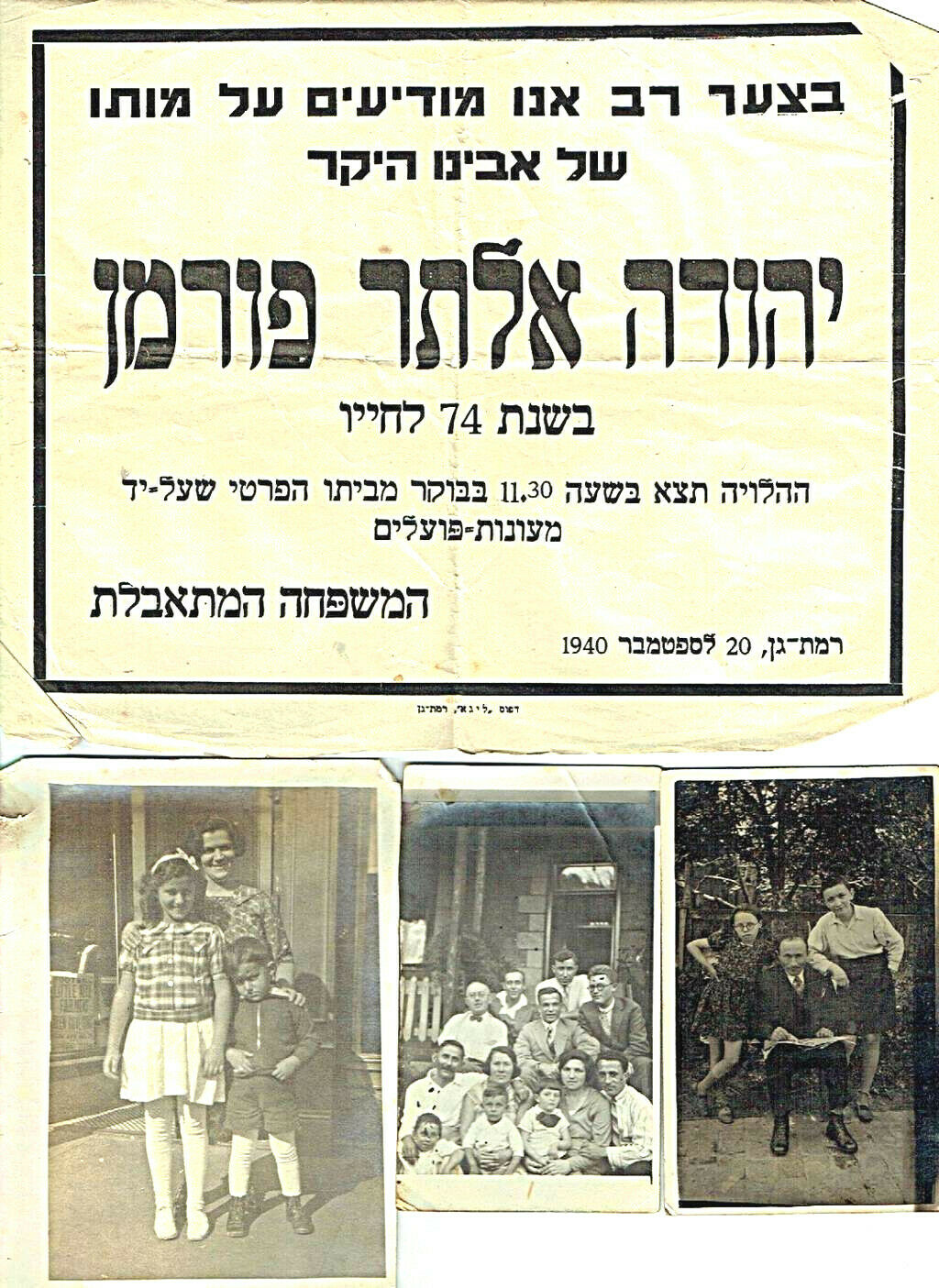

THE TORMENTED ARTIST BYRACHEL MARDER JUNE 3, 2012 21:46 The late painter Moshe Givati won’t get to experience his valiant return to the art world. Share on facebook Share on twitter Givati painting 370. (photo credit:Courtesy/PR) Moshe Givati had a reputation on Israel’s art scene for being difficult to work with. But no critic or curator could dismiss his raw talent and self-taught skill. After being largely absent from the Israeli art world since the 1990s, the 78-year-old artist was thrilled to return with a show of his work from 2006- 2010. But it was not meant to be. Givati succumbed to a heart condition on April 13 in Tel Aviv on the eve of the opening of his much-anticipated exhibition in New York City this week. Deena Lusky, the curator of Givati’s new show “Equus Ambiguity – Emergence of Maturity,” at Jadite Galleries, acknowledges that he was a complex person, but adds that the greatest of artists usually are. Be the first to know - Join our Facebook page. “He was very rough on the outside,” she says in a phone interview from New York with The Jerusalem Post. “He didn’t give a care, but on the other hand he had this person inside him that was so striving for acceptance.” It was this insecurity, Lusky says, that caused Givati, who took part in the major contemporary art groups in Israel like the 10+ Group (1965-1966), Tazpit (1964) and Rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry Project (1970- 1971) and showed in galleries in Israel and New York, to turn down opportunities for success over the years. Despite being a part of those movements, he never felt that he truly belonged. “From the beginning with Givati it was very hard to put him in a defined place,” Lusky says. Still, he longed to be acknowledged as the genius that he was. Known for his large-scale abstract paintings using bright colors and expressive figurative elements, the new Equus series is based on Givati’s experience seeing the play Equus in 1975 while living in New York from 1974-1982 just after the Yom Kippur War. In the ‘70s, he worked on the series inspired by the play about a psychiatrist trying to understand why a young psychotic boy chose to blind six horses. The show deals with the questions raised for Givati by the play, as well as his own maturation and the question of what it means to be a mature man. “It has nothing to do with age,” Lusky says. “It’s trying to live with the finding of who he is in his own eyes.” His paintings struggle with social and political issues as well, including one particularly poignant one of a frightened figure behind bars, which he stayed up all night working on during the night of captive soldier Gilad Schalit’s release. “He took to heart so deeply the pains of what was going on in Israel,” Lusky says. “He was a Jew and an Israeli at heart.” Born Moshe Hacohen Wexler in 1934 in Hadera to a mother with manic-depressive disorder, from which he also suffered, Givati’s parents, Yehudit and Moshe (for whom he was named), immigrated from Khotin, Bessarabia in 1933. His father died at 21, before he was born. Givati returned to Khotin when he was two years old to live with his grandmother, but his mother brought him back to Israel just before World War II broke out. In Israel, he struggled to keep up in school as he had dyslexia, and soon stopped attending classes before getting kicked out of the Beit Hinuch Workers’ Children School. Givati became active in the Zionist Hashomer Hatzair youth movement and began work on Kibbutz Shamir in the Upper Galilee. In the ‘70s, he lived in the artists’ colony Ein Hod and later moved to Haifa – it was during this time that he studied with Marcel Janco, the Romanian-Israeli artist best known as a leading figure in Dadaism. Givati shared one memory from his schooling. At around age 11 or 12, his art teacher Aaron Priver drew a horse on the blackboard and asked the class to copy it, threatening to slap their hands with a ruler if they didn’t. Lusky postulates that his early artistic encounter with horses contributed to his later interest in Equus. While living in New York, Givati did not paint very much, but rather focused on printmaking and textiles. When he returned to Israel, Lusky says he reached a low point personally, drinking excessively and using drugs, though he continued to garner praise from art critics for his four-panel abstract landscapes and formulation. “My head must always be in a slightly blurry state; this is the only way I can go through life,” he had said. While he continued to paint in the ‘90s, including a series of landscapes from Jerusalem of Arab villages over the 1967 lines, opening “Studio Givati” in a large loft in Tel Aviv and selling works to collectors who visited him, he intentionally disconnected himself from the mainstream art scene as he struggled financially and with his health, suffering his first heart attack in 1993. Unable to meet mounting debts, Lusky says Givati found himself homeless and working as a dishwasher and juice squeezer at Tel Aviv’s old Central Bus Station. After a year, hotel owner and art collector Haim Shiff, who had purchased Givati’s paintings in the past, offered him a room at the Marina Hotel in Tel Aviv. Haim’s son Dov (Dubi) Shiff became Givati’s benefactor after his father passed away. Always open about his mental disorder, Givati said, “Painting is my mania, and as a mentally-ill person I cannot demand anything from the authorities. Being an artist is my privilege, God’s gift, and just as a religious man reports every morning to pray to his Creator – fearlessly – thus the artist wakes up every morning for his art prayer, and must not expect anything in return.” His last show was a retrospective of his work in 2006 at the Tel Aviv Museum, but Lusky says the exhibition did not show much of his later work. After being told by curators and art consultants that Givati was considered a “has been,” also because he designed works for his benefactor’s hotel interiors, Lusky says she became determined to reintroduce the artist to the world when Dubi Schiff approached her about working on an exhibition. Refusing to ever title his paintings or really verbalize what they were about, Givati insisted that it was up to the viewer to understand whatever he wanted from his deeply personal work. “I am not a philosopher or an intellectual,” he said. “I paint beautiful paintings. On the other hand, if art lovers find ideas in the paintings, they are experiencing their own discovery. My touch on the canvas is my story.” The exhibition in New York will run until June 30 before traveling to Los Angeles, and then Europe before possibly showing in Israel, Lusky says. For a man for whom the canvas was his confidante, he looked forward to sharing his inner world with the public again. “For him it was like a dream come true,” she says of the exhibition. “He said to me, ‘in viewing my art there will be people who will look at it and continue on. But the ones who feel a connection to something that I’m expressing in my painting won’t ever want to leave it. They’ll want it in front of their face continuously.” ***** The Wandering Jewish Artist: A Portrait of Moshe Givati (PHOTOS) By Shira Hirschman Weiss · · · · British author Robert Louis Stevenson once said “To be what we are, and to become what we are capable of becoming, is the only end of life.” For the Israeli painter Moshe Givati, who died at age 78 this past April, the “end of life,” what he became and the fruits of his final intensive labors can be seen posthumously at the Jadite Galleries in Manhattan. His artwork is being showcased there until June 30, when it is transferred to a gallery in Los Angeles. Givati’s last few months could be characterized by the vibrantly colorful paintings he stayed up nights to create, each displaying symbolic images reflecting the inner workings of a troubled mind. The son of a manic depressive mother, Givati was prone to his own highs and lows and extremes. Back in the ‘80s, he suffered from both alcohol and drug addictions. Looking forward to his June “comeback” exhibition, he told Jadite’s art curator Deena Lusky earlier this year that “after 20 years, I am finally getting the chance to show my work.” Perhaps, like Stevenson’s quote, Givati felt he was becoming what he was capable of becoming after years of dodging opportunities. It was his intense fear of success that led him to run from it. In his final months however, Givati invested heart and soul, and ultimately, jeopardized his fragile health to perfect his final exhibition, a series of paintings that held personal symbolic significance to him and were based on his favorite play, “Equus.” The play is about a psychiatrist’s analysis of a boy who blinded six horses. The exhibition not only celebrates an abstract collection but serves as a reminder of a life extinguished in what was to be its wintry prime. Lusky explains that Givati had made himself scarce for the last 20 years. “From the moment he was born, he had no roots,” she says of his dysfunctional upbringing, “He was a wandering Jew at heart and not a happy one. He always tried to find the right equilibrium to manifest all the things that were going on inside of him.” Like other talented manic depressives before him (though it is unclear if Givati was ever officially diagnosed), Givati’s highs were very high. For Lusky, that was evident by the sleep and nourishment he forfeited to perfect the Equus collection in his final months. “It wasn’t that Moshe Givati didn’t have chances along the way,” Lusky explains, “but he was skeptical of many of them because his own success terrified him.” To drown out the insecurities and avoid his own personal problems (he was married twice and had difficult relationships with four of his five children), he turned to drugs and alcohol and spent long periods as a recluse. His last show, prior to the current exhibition, was a retrospective of his work in 2006 at the Tel Aviv Museum, but it did not show the more recent work he was proud of. “When most other opportunities came his way, he would run away,” Lusky relates, “And his art was always valued as swaying between the meditative and expressive. He didn’t use a color palate. He simply took his brush and stuck it into whatever color and smeared that onto canvas. He had open dialogue with the canvas; it was the only friend he really trusted that would absorb all his insecurities.” Whereas Givati refused to title his paintings or provide commentary, contending that is was up to his viewers to interpret, Lusky (who came know Givati well before he died) feels that the horses in his 45 painting Equus series represented the lust and deep longing for acceptance, the insecurities he lived with and his personal triumphs. For her, the series represents “the torture of the struggle of living here on earth.” Lusky says that Givati was deeply spiritual but not unlike his pendulum swinging mood shifts and chaotic personal relationships, he had a love-hate relationship with his own religion. At one point while living in New York, he connected with the Chabad movement and became a baal teshuva, fully embracing his Jewish roots after living a secular lifestyle. However, at the time of his death, he was angry at God and for all intents and purposes considered himself an atheist. During his religiously observant period however, Lusky says, “Yiddishkeit (a love of Judaism) and stories from the Torah and the midrash brought out his vitality. But then, when he returned to Israel from New York, his mother died and that was followed by the death of his best friend. He said, ‘I don’t want to know any God’ and went back to his old ways.” Revisiting his addictions from years before, Givati began drinking and abusing drugs. As a result, he eventually became homeless. It was at this point in time that one of the more prominent art collectors in Israel, Chaim Shiff, who had bought numerous Givati paintings, offered the artist room and board at hotels in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv in exchange for a monthly stipend affording him to paint. After Schiff passed away, his son Dov continued to support Givati for the rest of the painter’s life. Givati would become known as a “hotel painter” to many in the art world, a difficult box to take himself out of which made the prospect of his June exhibition all the more significant to him. “His relationship with God is so much a part of his art,” says Lusky, explaining that Givati had a series of paintings about the sacrifice of Isaac and another in which Joseph’s coat of many colors is displayed. “If you asked him, he wouldn’t say a word but you see that it’s a search into his spirituality.” Lusky tells a story of how she visited Givati in the hospital during his final days and he tersely did not want her to mention Hashem, a Hebrew term for God. He also made it clear to the son who arranged his funeral that a secular burial was to take place and no kaddish (the mourner’s prayer) would be said. Even on his deathbed, Lusky says, “Moshe Givati always went to the extreme.” For Givati, emotion and being overly emotional is what fueled his most passionate works of art. As American literary critic George E. Woodberry once wrote: “By passion, the artist enters into life more than other men. That is his gift — the power to live. Emotion is the condition of their existence; passion is the element of their being.” Givati’s vitality and intensity is evident in the works he left behind. He was connected to Israel and passionate about the country’s politics. One of his untitled paintings was created fervently the night Gilad Shalit was released from captivity. Lusky says that Givati frequently spoke about “the torture and the conflict.” He didn’t necessarily give his political opinion, but through his art, he displayed how he viewed political and social issues. Although he was notoriously difficult to work with in the art world, his self-taught technique and raw talent were something that no art connoisseur could overlook. For Givati, the play “Equus” raised questions about maturity, and his current exhibition amplifies the questions he had regarding his own maturation, what it means to be a mature man in general and who he was in his own eyes. Sadly, no one can interview Moshe Givati and ask him who he thinks he was in his own eyes. But like his untitled and unexplained paintings, he has left that to us to decide. *** Moshe Givati to be revived in NY By Viva Sarah Press MAY 20, 2012, 5:52 AM Image: Moshe Givati · SHARE3 · TWEET · SHARE · COMMENT · EMAIL Image: Moshe Givati The New York art scene is abuzz as Jadite Galleries gets ready to launch Moshe Givati‘s newest solo exhibition (June 5-30). The event, called Equus Ambiguity – The Emergence of Maturity, was meant to mark the acclaimed Israeli artist’s resurfacing on the art scene – but took a bittersweet turn when Givati passed away recently, just two months before the exhibit opening. Image: Moshe Givati His Equus series of paintings — based on the Broadway play “Equus” by Peter Shaffer –are described as “expressing the lifelong dilemma of searching for the source of his creativity while desperately seeking the equilibrium needed to survive in this world.” Image: Moshe Givati The Hadera-born Givati had lived in New York in the 1980s. The possibility of exhibiting his paintings in the Big Apple energized him to paint again (he had taken a personal hiatus) and he was in the middle of exciting works when he passed away. Image: Moshe Givati Givati was born in 1934 and was a member of Kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim. He studied with Marcel Janco and at the Avni Art Institute, but acquired most of his painterly education by observing young art in exhibitions throughout Israel in the 1960s.