-40%

4 ORIGINAL TARKAY LITHOGRAPHS Israel HAND SIGNED Limited FINE ART BOOK Judaica

$ 197.47

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Up for auction is a HANDSOME and quite RARE FIND. It's a BIBLIOPHILIC GEM . An ART BOOK in MINT-PRISTINE condition , One of a SIGNED and NUMBERED serie of only 4400 copies EDITION -

ORIGINAL hand SIGNED , LIMITED and NUMBERED Jewish - Judaica BOOK with FOUR ORIGINAL plate

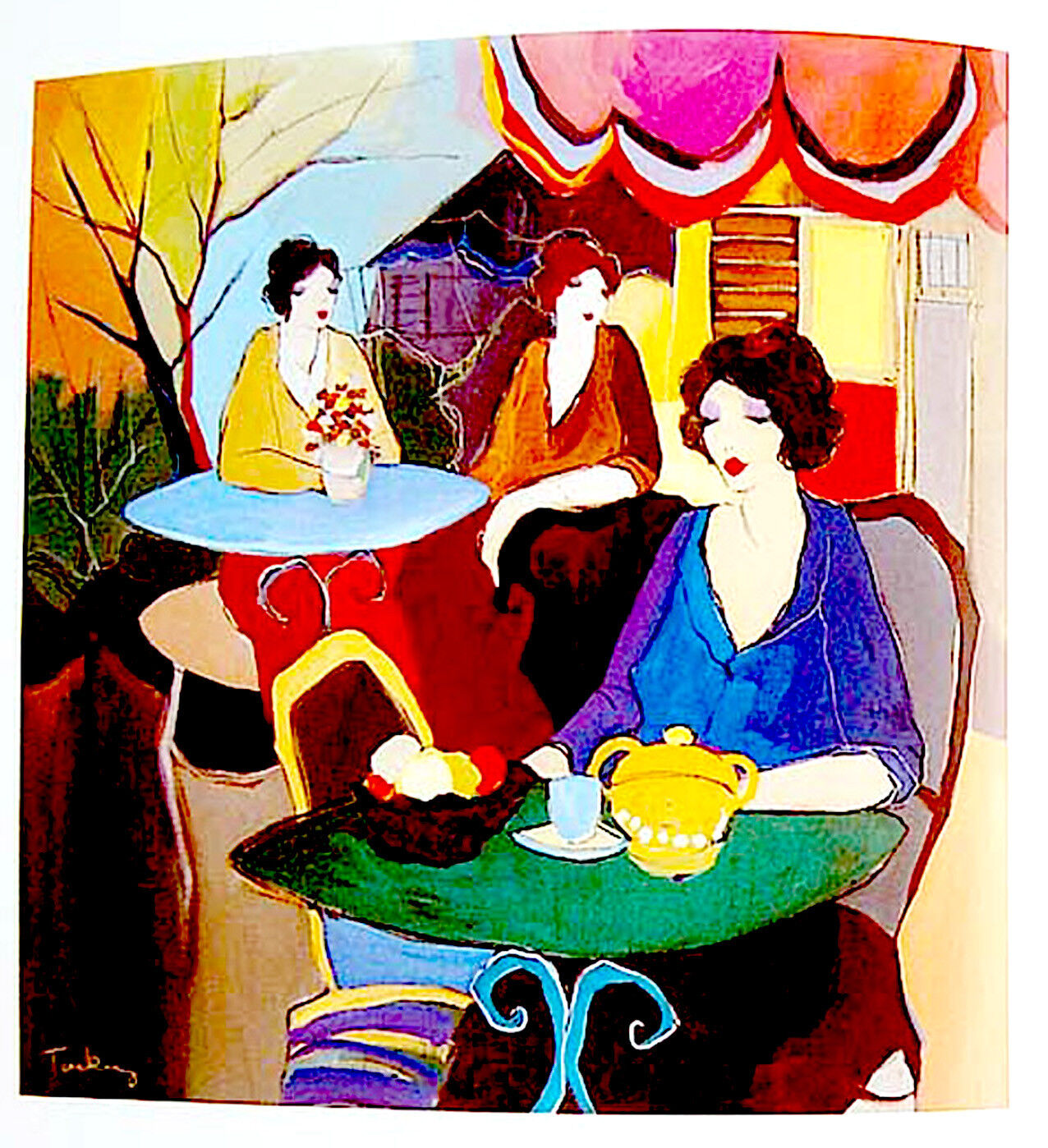

SIGNED COLORFUL LITHOGRAPHS

by the acclaimed Israeli artist , The painter YITZCHAK TARKAY . The LUXURIOUS BOOK named "YITZCHAK TARKAY - WORKS ON PAPER" depicts TARKAY Lithographs , Watercolors and other media on PAPER. Published ( FIRST AND ONLY EDITION ) in 1993 in a limited edition of only 4400 copies , Of which only 400 are HAND SIGNED and NUMBERED by the artist ( This specific copy is indeed HAND SIGNED but not numbered ). TARKAY loves WOMEN and his women are always HANDSOME , often erotic, Quite a few NUDES .

THREE full page ORIGINAL LITHOGRAPHS are bound with the book and one double spread LITHOGRAPH is the DUST JACKET. On-line copies sell for around 0 up to 0 .

ENGLISH . Illustrated Double spread ORIGINAL LITHOGRAPH DJ. Luxurious illustrated leather immitation HC with GILT ILLUSTRATION . Around 9.5 x 12". 142 throughout illustrated pp on extremely heavy paper of excellent quality. 3 ORIGINAL LITHOGRAPHS bound with the book .

Around 90 reproductions of lithographs and watercolors.

FOUR ORIGINAL

LITHOGRAPHS. Pristine MINT condition. Practicaly unused.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )

. The book will be sent in a special protective rigid sealed packaging.

AUTHENTICITY

: This is an ORIGINAL vintage HAND SIGNED and NUMBERED BOOK with FOUR original SIGNED in the plate LITHOGRAPHS , NOT a reproduction or a reprint , It holds life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

: P

ayment method accepted : Paypal & All credit cards .

SHIPPMENT

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 39 .

The book will be sent in a special protective rigid sealed packaging

.

Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

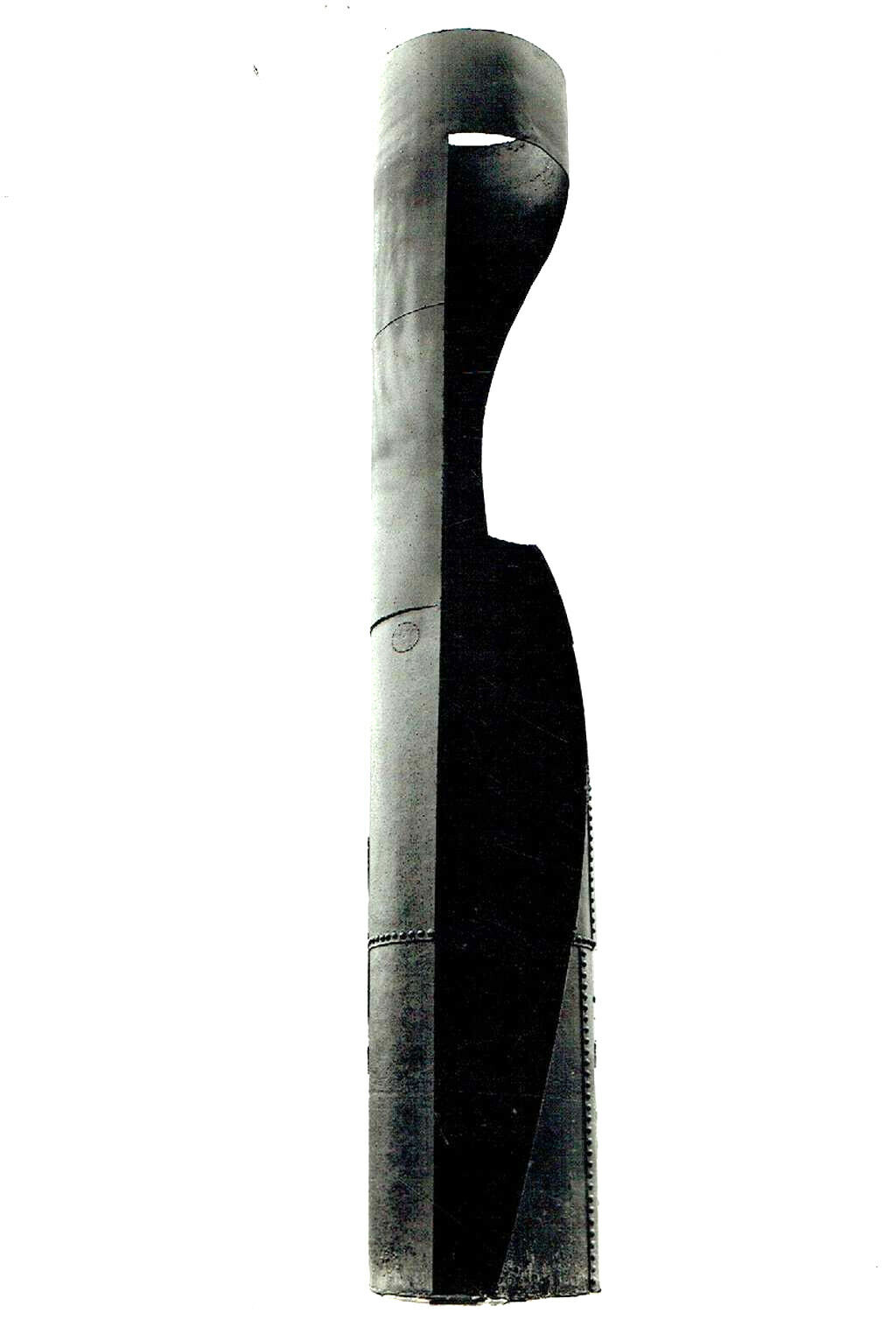

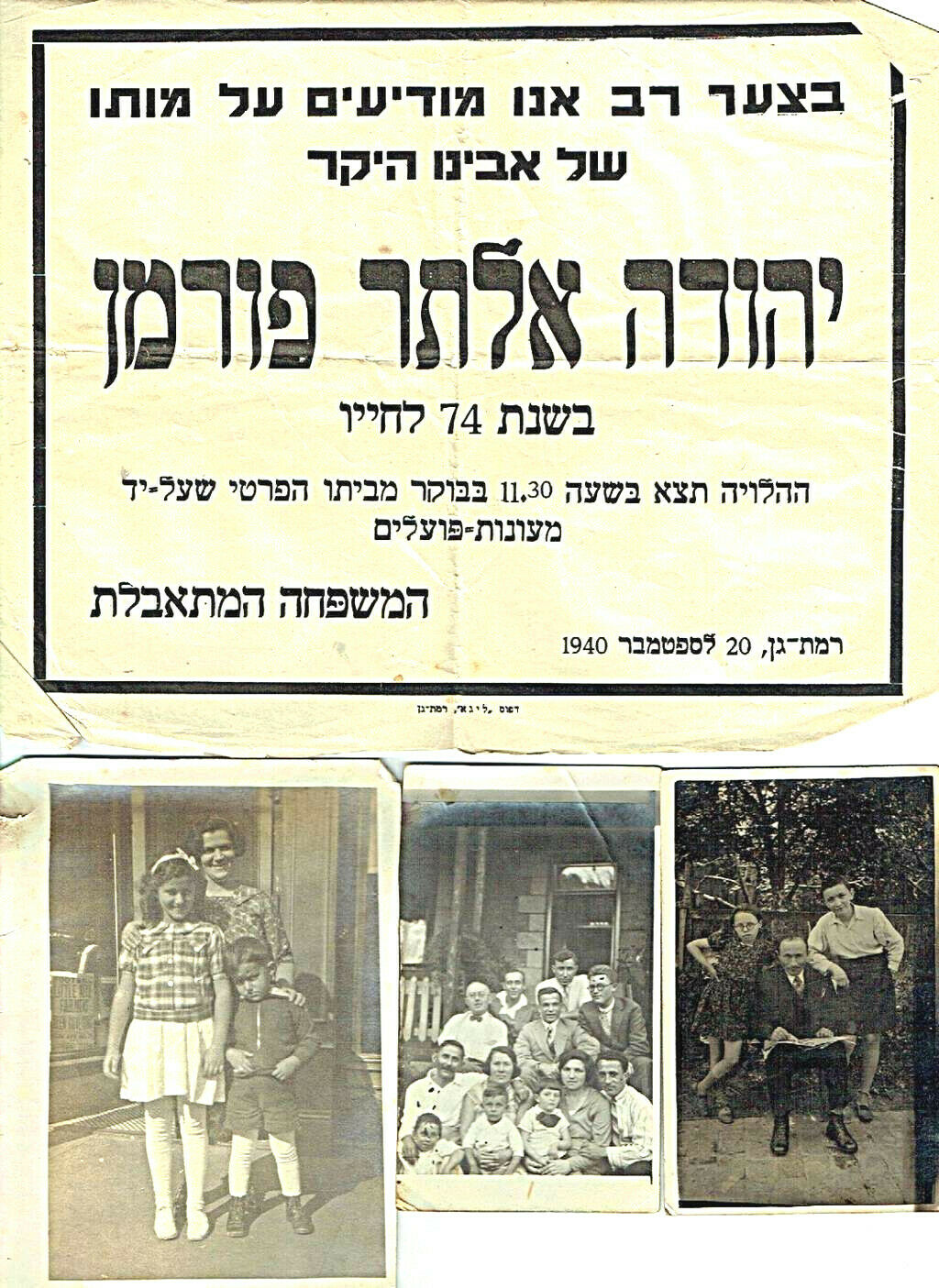

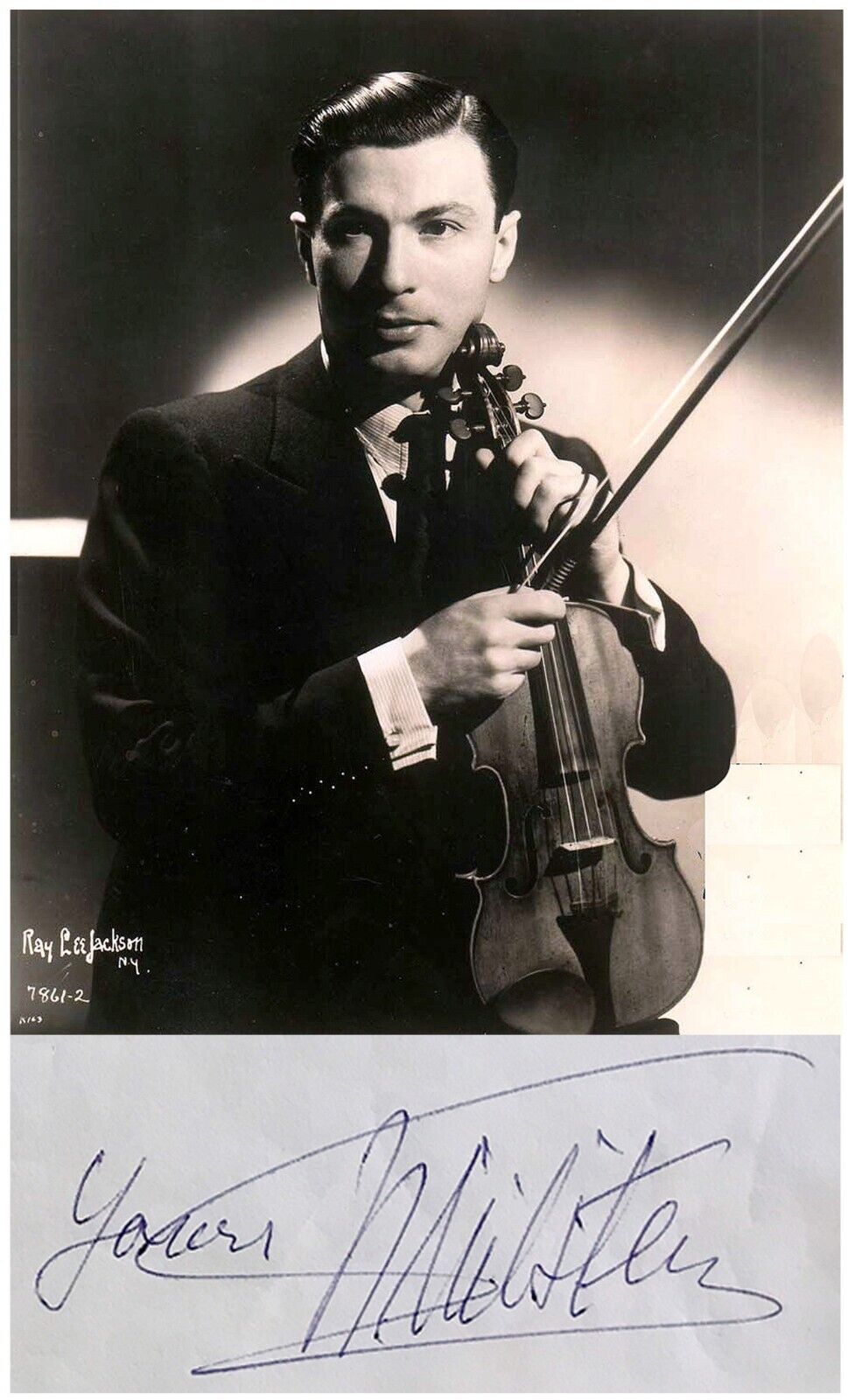

Itzchak Tarkay (1935 – June 3, 2012) was an Israeli artist. Tarkay was born in 1935 in Subotica on the Yugoslav-Hungarian border. In 1944, Tarkay and his family were sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp, until Allied liberation freed them a year later. In 1949 his family emigrated to Israel, living in a kibbutz for several years. Tarkay attended the Bezalel Academy of Art and Designfrom 1951, and graduated from the Avni Institute of Art and Design in 1956. His art is influenced by French Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism, particularly Matisse and Toulouse-Lautrec. His work was exhibited at the International Art Expo in New York City in 1986 and 1987. He has been the subject of three books, published by Dr.Israel Perry. Perry Art Gallery And Park West Gallery, his dealer. His art is focussed on almost dream images of elegant women in classical scenes which draw you into an imaginary world. History quoted from the website of his dealer, Park West Galleries: "Itzchak Tarkay was born in 1935 in Subotica on the Yugoslav-Hungarian border. At the age of 9, Tarkay and his family were sent to the Mathausen Concentration Camp by the Nazis until Allied liberation freed them a year later. In 1949 his family immigrated to Israel and was sent to the transit camp for new arrivals at Beer Yaakov. They lived in a kibbutz for several years and in 1951 Tarkay received a scholarship to the Avni Art Academy where he studied under the artist Schwartzman and was mentored by other important Israeli artists of the time such as Mokady, Janko, Streichman and Stematsky. Tarkay achieved recognition as a leading representative of a new generation of figurative artists. The inspiration for his work lies with French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the color sophistication of Matisse and the drawing style of Toulouse-Lautrec. He drew upon the history of art to create many of his compositions, designing a kind of visual poetry from the aura of his cafes and intimate settings. As well as being an acrylic painter and watercolorist, Tarkay was a master graphic artist and his rich tapestry of form and color was achieved primarily through the use of the serigraph. In his serigraphs, many colors are laid over one another and used to create texture and transparency. When asked about his technique, Tarkay said it’s impossible to describe. “Can you explain your own handwriting?” he asked. He used his instinct to choose his colors and couldn’t define any other reason. “The color is coming,” he said. “When it’s finished, sometimes I’ll change the colors. It’s not something I think about.” Most of his choices were instinctive – inspired by his surroundings, the music he listened to, the places where he traveled and nature. Very often, Tarkay painted “en plein air” and brought his sketchbook outdoors. As it grew dark, he would take a series of photos and finish the work in his studio. Tarkay said that the most difficult part of his painting is realizing when a work is complete. He recalled going to a show once after he had not seen his paintings in about three months, having the urge to re-touch each piece. To him, the works were never done. In the later years of his life, Tarkay shared his gifts by mentoring younger Israeli artists including, David Najar, Yuval Wolfson and Mark Kanovich who often visited his studio, worked alongside him and received his critiques. Tarkay was also the only artist to collaborate with Israeli master, Yaacov Agam (1928). He and Agam created two paintings which incorporated both artists’ imagery in a single painting. Tarkay spent between five and six hours each day in the studio, six days a week. While he had very little free time, he enjoyed going to concerts, reading books and listening to music, and visiting friends. Tarkay expressed how much he enjoyed meeting his collectors and his happiness to work with the other artists when working with Park West. He felt no sense of competition with them – only love – and was proud to have such a wonderful relationship with the artists, collectors, and gallery. In an excerpt from “Itzchak Tarkay” (1993) by art historian, author, and critic, Joseph Jacobs, PhD, the author writes: Itzchak Tarkay is a refreshing anomaly in today’s art world, and perhaps it can even be said that his work, which seems to stand outside of the mainstream, nonetheless anticipates the direction of art in the near future. In a world so preoccupied with being politically correct, with dealing with social issues, with making art that is anything but painting, Tarkay holds onto timeless, universal values–to values that have staying power and do not simply ride the tide of fashion. In contrast to the work of so many of his contemporaries, it will be impossible to look back on his work in the twenty-first century and describe it as dated. Unlike so many artists working today, Tarkay believes in painting and he believes in beauty. Aesthetics and human psychology are the forces that drive his art, not vogue. He has no need of video, mixed-media installation or site-specific sculpture, all of which are the rage of such art centers as New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, London, Paris, Cologne, or Milan. Instead he makes art ‘the old-fashioned way’ — applying paint to canvas, or printer’s ink to paper. In other words, he makes the art of the future — the art that artists invariably come back to, the art that lasts and holds up to the test of time. … It is clear that Tarkay, who studied with Mokady, Janko, Schtrichman and Stematsky at the Avni Institute of Art in Tel Aviv, is thoroughly grounded in European artistic traditions. There are touches of Bonnard, Vuillard, Picasso, Modigliani, Klimt, and Magritte in his art, which includes drawings and prints. His work, however, does not look like that of any of these masters. But he shares many of their aesthetic values, and in particular, the idea that art should not proselytize or preach, but instead should deal with timeless issues. After exhibiting both in Israel and abroad, Tarkay received recognition at the International Artexpo in New York in 1986 and 1987 for works in several forms of media, including oil, acrylic and watercolor. Today, Tarkay is considered one of the most influential artists of the early 21st century and has inspired dozens of artists throughout the world with his contemplative depiction of the female figure. Three hardcover books have been written on Tarkay and his art, the most recent, “Tarkay, Profile of an Artist,” was published in 1997." link= Family[edit] Itzchack Tarkay married Bruria Tarkay, and has two sons, Adi and Itay Tarkay. ITZCHAK TARKAY (1935-2012) Itzchak Tarkay was born in 1935 in Subotica on the Yugoslav-Hungarian border. At the age of 9, Tarkay and his family were sent to the Mathausen Concentration Camp by the Nazis until Allied liberation freed them a year later. In 1949 his family immigrated to Israel and was sent to the transit camp for new arrivals at Beer Yaakov. They lived in a kibbutz for several years and in 1951 Tarkay received a scholarship to the Avni Art Academy where he studied under the artist Schwartzman and was mentored by other important Israeli artists of the time such as Mokady, Janko, Streichman and Stematsky. Tarkay achieved recognition as a leading representative of a new generation of figurative artists. The inspiration for his work lies with French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly the color sophistication of Matisse and the drawing style of Toulouse-Lautrec. He drew upon the history of art to create many of his compositions, designing a kind of visual poetry from the aura of his cafes and intimate settings. As well as being an acrylic painter and watercolorist, Tarkay was a master graphic artist and his rich tapestry of form and color was achieved primarily through the use of the serigraph. In his serigraphs, many colors are laid over one another and used to create texture and transparency. When asked about his technique, Tarkay said it’s impossible to describe. “Can you explain your own handwriting?” he asked. He used his instinct to choose his colors and couldn’t define any other reason. “The color is coming,” he said. “When it’s finished, sometimes I’ll change the colors. It’s not something I think about.” Most of his choices were instinctive – inspired by his surroundings, the music he listened to, the places where he traveled and nature. Very often, Tarkay painted “en plein air” and brought his sketchbook outdoors. As it grew dark, he would take a series of photos and finish the work in his studio. Tarkay said that the most difficult part of his painting is realizing when a work is complete. He recalled going to a show once after he had not seen his paintings in about three months, having the urge to re-touch each piece. To him, the works were never done. In the later years of his life, Tarkay shared his gifts by mentoring younger Israeli artists including, David Najar, Yuval Wolfson and Mark Kanovich who often visited his studio, worked alongside him and received his critiques. Tarkay was also the only artist to collaborate with Israeli master, Yaacov Agam (1928). He and Agam created two paintings which incorporated both artists’ imagery in a single painting. Tarkay spent between five and six hours each day in the studio, six days a week. While he had very little free time, he enjoyed going to concerts, reading books and listening to music, and visiting friends. About working with Park West, Tarkay expressed how much he enjoyed meeting his collectors and his happiness to work with the other artists. He felt no sense of competition with them – only love – and was proud to have such a wonderful relationship with the artists, collectors, and gallery. After exhibiting both in Israel and abroad, Tarkay received recognition at the International Artexpo in New York in 1986 and 1987 for works in several forms of media, including oil, acrylic and watercolor. Today, Tarkay is considered one of the most influential artists of the early 21st century and has inspired dozens of artists throughout the world with his contemplative depiction of the female figure. Three hardcover books have been written on Tarkay and his art, the most recent, “Tarkay, Profile of an Artist,” was published in 1997. Itzchak Tarkay by Joseph Jacobs, Art Historian, Author and Art Critic Itzchak Tarkay is a refreshing anomaly in today's art world, and perhaps it can even be said that his work, which seems to stand outside of the mainstream, nonetheless anticipates the direction of art in the near future. In a world so preoccupied with being politically correct, with dealing with social issues, with making art that is anything but painting, Tarkay holds onto timeless, universal values--to values that have staying power and do not simply ride the tide of fashion. In contrast to the work of so many of his contemporaries, it will be impossible to look back on his work in the twenty-first century and. describe it as dated. Unlike so many artists working today, Tarkay believes in painting, and he believes in beauty. Aesthetics and human psychology are the forces that drive his art, not vogue. He has no need of video, mixed-media installation or site-specific sculpture, all of which are the rage of such art centers as New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, London, Paris, Cologne, or Milan. Instead he makes art "the old-fashioned way" -- applying paint to canvas, or printer's ink to paper. In other words, he makes the art of the future -- the art that artists invariably come back to, the art that lasts and holds up to the test of time. It is almost ironic that Tarkay goes against the grain of contemporary trends by making art that does not deal with social issues. More than most of his contemporaries, he has good reason to make work that focuses on social injustices, for he was sent to a concentration camp by the Nazis. Born in 1935 in Subotica on what was then the Yugoslav-Hungarian border, he was interred in the Mathausen camp in 1944, when he was nine years old. At the war's end, his family returned to Subotica. They then immigrated in 1949 to Israel, where he still lives and works. There he continued to witness life's injustices as his young adopted country struggled to survive in a climate of violence. But Tarkay's art is not ostensibly about these things. It is not about Nazi oppression, or the Mideast crisis. It is as though Tarkay realizes that the great world art does not overtly and literally deal with these kinds of issues. Raphael, Rubens, Rembrandt, Tiepolo, Monet, Matisse, Picasso, Modigliani and Klimt couched political and social concerns, when present in their work, in symbolism and allegory. Their imagery generally dealt with humanity instead, and operated at a universal level -- and so does Tarkay's. All of Tarkay's images strike the same note: a haunting, meditative stillness which is lush, sensuous, and ethereal. His oeuvre is dominated by pictures of women who are exceptionally well-dressed and seated in lavish interiors or on terraces. Nothing moves. Even when there are two or more women in the same scene, there is no physical connection between them. They sit or lounge in silence; there is no dialogue or eye contact. There is a sense of isolation, which is at odds with the wealth of fine materials in which they are immersed. There is the promise of riches--of lush fabrics, furniture, clothing, paintings, expensive food and drink--all of which is in a sense symbolized by the rich, red, sensuous lips of his female sitters. These women have the world's delights at their fingertips. But these riches do not seem to matter. Time prevails over the material world. This powerful psychology that deals with the transience of the material world is reinforced by Tarkay's handling of the medium, whether it is paint or printer's ink. The artist's message is so powerful because of his ability to create rich, sensuous textures, a deep saturated palette and extremely complex but harmonious compositions. His command of the medium can be readily seen in his prints. Because they are multiples as opposed to unique works of art, prints, quite mistakenly, are often considered a secondary medium. But in Tarkay's hands it is clear they are not. One look at a work such as In the Lounge, and it can be immediately seen that the artist has a powerful affinity for the physicality of the printer's ink that virtually transforms this silkscreen into a painting. We can see and feel the three-dimensionality of the ink; it is rich and unctuous, like oil paint. We would hardly know that the pigment was squeezed onto the paper through a fine screen as opposed to being applied with a brush. Tarkay works with layers and layers of pigment, and we can feel each of these layers or screens. We can sense the artist's presence as he determines the linear patterning of the dress of the woman sitting in the immediate foreground, or the bold sweep of the blossoms on the skirt of the figure who dissolves into the lower right corner of the picture. The lines that subtly cross-hatch much of the image look like Tarkay has taken the handle from his brush and dug it into the "paint" to reveal layers of pigment underneath. But of course, there is no paint per se, and no paint brush used. The successive layers of thick, rich color that he has applied through screens are unusually tactile and three-dimensional, making it almost impossible not to tell that this is not an oil painting. As we go from one print to the next, we can see the broad range of Tarkay's use of the medium. In Lady in Red, the artist has applied what looks like a layer of varnish to portions of his image, giving a dark, glossy and painterly look to these sections. These touches can be seen, for example, in the red flower on the sitter's skirt. The "varnish" even appears to be dripping from the bottom of the dress and streaking down toward the foot of the print. Tarkay has given us the sense that his black line drawing is the result of quick, deft strokes of his loaded paint brush. This can be seen, for example in the drawing on the ruffs on the sitter's sleeves. On her left arm, the artist has given us a highly raised line of light blue, rather than black paint. In contrast to this thick rich line, some of the black drawing that rings the sitter's bodice is dry and broken, giving the impression that his "paint brush" is not so loaded with oil and is instead somewhat dry. In Sophisticated Lady, we can see the same wiry drawing, sometimes rich and unctuous as on the sitter's dress, other times dry and broken, as on the woman's right leg. In addition, the print has a large amount of "varnish" overlay, which makes it seem especially sensuous. In contrast, the background, to both the right and the left, has thin layers of streaked paint, adding one more textural element to the artist's exceptionally rich printmaking vocabulary. In other works, Tarkay manipulates his screens and printer's ink to create works that take on the character of drawings, rather than paintings. For example, Repose looks like a watercolor with some pencil and pen and ink drawing on it. The thin scrims of "wash" on the background wall or surrounding the figures appear as though they were applied with a watercolor brush, while the grey drawing of the bottle on the table resembles graphite. The dark, black lines that make up the table or ring the women's hair take on the appearance of pen and ink drawing. In a work such as Journee d'ete, it almost appears as though the artist has added touches of gouache, especially in the dark red lines that make up the limbs of the tree. And characteristic of much watercolor drawing, Tarkay has left patches of his paper unprinted and bright white, as in the figure's face and arms, and in the two left corners of the print. In a work such as Souvenirs, the artist has suggested an even greater use of gouache. For example, the ink is especially rich and gouache-like in the bright yellow flowers on the one woman's dress, and in the light-blue, curved and dash-like marks that sit on the unidentifiable object that is below and to the left of the vase on the table. In a work such as Dans le Salon, there is no suggestion of gouache, but instead the print appears to be enriched by "crayon" drawing, as seen in the rust-colored vertical lines that cover portions of the sitter's lower body. Tarkay even suggests that there is some charcoal mixed in with this crayon drawing, which can also be seen on the heads of the figures seated in the background behind the sitter's couch. In areas, the artist powerfully reinforces the sense of watercolor by allowing his colors to run or streak down the paper, as in the washed-out purple plane in the lower right corner, or the thin brown wash that is just under the left side of the couch. In keeping with the look of a drawing, a large portion of the paper is left unprinted and white, which is also true of Pensees Secrets, where the image bleeds and disappears into the exposed paper in all four corners. Tarkay's prints are testimony to the extraordinary technical richness of printmaking and the degree to which it can be transformed into a medium of great personal expression. The artist has turned printer's ink into oil paint, varnish, glazes, watercolor, wash, gouache, graphite, pen and ink, brush and ink, crayon and charcoal. The artist's touch is so prominent, it is hard to believe that for any print there could be another example that is even similar in appearance. It is clear that Tarkay has remarkable command of his formalist vocabulary. He creates especially sensuous and rich surfaces, highly varied in color and texture. As already mentioned, his compositions are extremely complex, and yet they are always perfectly balanced. But it is the abstract components to his works that lend them meaning; they are not idle exercises in making beautiful images. For example, in Morning Talk we see an extraordinarily sensuous and luxurious image. The violet-yellow print of the sitter's dress, the deep resonating blues of the sofa, the blue-brown-orange checkerboard pattern of the floor, the yellow and white tea service, the variety of shapes, textures and hues of the flowers, all register as fine objects as well as dazzling sumptuous colors and textures. It is clear that the women are women of leisure and money; their lives go beyond being just comfortable. Their world even includes fine paintings, as we can see from the picture on the wall in the background. Yet, despite this wealth, there is an underlying nervousness to the images, in part triggered by the lack of connection between the figures. It is reinforced by the abstract components of the composition as well. There is a nervousness to Tarkay's line, which is not always curvilinear and undulating; instead there are moments when it is brittle and angular and has sharp edges--as can be seen, for example, in the lines that make up the flower pots or the outlines of the figures. A tension also comes from the various shapes that are pointed and piercing, as can be seen in the uppermost leaves of the plants, the bottom-most portion of the fore-ground sitter's dress, or the bottom of the sitter's dress at the neckline. Unsettling as well is the haunting skeletal quality to Tarkay's line, perhaps best seen in the tree, bush or plant on the right edge of the image, but also in the yellow linear drawing on the three background figures. Tarkay also creates tension by setting up disquieting dialogues between objects and shapes. For example, the painting on the wall contains a glowing orange form that plays off of four vertical brown bars. These bars, in turn, seem to echo the four women and the four plants of the foreground, suggesting an unexplainable connectedness. And if we look carefully, we can see that most shapes are echoed by similar forms elsewhere in the image. The dark blue balls embedded in the sofa can be found to the immediate right in the yellow flowers in the left most pot. In a work such as Fame, we can find even more extensive use of Tarkay's haunting, skeletal line. The chair, for example, in the right foreground is entirely insubstantial, simply a ghost of a chair, while the trees in the background have twigs for trunks and branches. In Cafe Danielle much of the background to the right is line drawing, to the extent that the figures in a doorway look like ghosts. Similarly, the left side of the tree in the center seems to lose its leaves as it is reduced to defoliated twigs. Of course, these linear components to some degree exist simply to increase the textural surface of the image and make it richer and more varied, and thus more visually interesting. But we cannot ignore the literal or symbolic implications of Tarkay's use of line. Another haunting device that Tarkay uses is his animation of inanimate objects. For example, both tables in Three Women at Tea seem anthropomorphic, for the legs seem to twist and turn and come alive. The same is true of the arm on the background chair to the left in Serenity. We can see the animated energy in the back and arm of the foreground chair in Summer Cafe, and in the legs of the table in the background, which literally make the table look like it is about to walk off. As haunting is the way in which Tarkay has split in half the faces of the two women in the foreground, in part to reflect the play of light and shadow on the face, but also to impart the time-honored surrealist device of Picasso to suggest different states of minds, or different psychologies. Which brings us back to the real issue at hand, which is how underneath these rich, luxurious, sensuous surfaces and behind these rich, luxurious, sensuous worlds there lay other realities. There is a sense of transience and of the spiritual. There is a sense that there is something more important than the material world; that the material world is controlled by something infinitely more important, perhaps even something spiritual. It is clear that Tarkay, who studied with Mokady, Janko, Schtrichman and Stematsky at the Avni Institute of Art in Tel Aviv, is thoroughly grounded in European artistic traditions. There are touches of Bonnard, Vuillard, Picasso, Modigliani, Klimt, and Magritte in his art, which includes drawings and prints. His work, however, does not look like that of any of these masters. But he shares many of their aesthetic values, and in particular, the idea that art should not proselytize or preach, but instead should deal with timeless issues. Joseph Jacobs New York, New York September 9, 1993 ***** At the age of 9, Tarkay and his family were sent to the Mathausen Concentration Camp, until Allied liberation freed them a year later. In 1949 his family immigrated to Israel, living in a kibbutz for several years. By 1951 he had received a scholarship to the Bezalel Art Academy where he studied under the artist Schwartzman. Until his graduation from the Avni Institute of Art in 1956, Tarkay learned a great deal from many famous artists of the time, such as Mokady, Janko, Schtreichman and Stematsky. Tarkay has achieved recognition as a leading representative of a new generation of figurative artists. The inspiration for his work clearly lies with French Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism, particularly the color sophistication of Matisse and the drawing style of Toulouse-Lautrec, while summing up the characteristics of his model subject without relying on the precise copying of natural forms, or the patient assembling of exact detail. As well as being a painter and watercolorist, Tarkay is a master graphic artist and his rich tapestry of form and color is achieved primarily through the use of the serigraph. In his serigraphs, many colors are laid over one another and used to create texture and transparency. After exhibiting both in Israel and abroad, he received recognition at the International Art Expo in New York in 1986 and 1987 for works in several forms of media, including oil, acrylic and watercolor. Today, Tarkay is considered one of the most influential artists of the early 21st Century and has inspired dozens of artists throughout the world, with his contemplative depiction of the female figure. Three hardcover books have been written on Tarkay and his art, the most recent, Tarkay, Profile of an Artist was published in 1997. EBAY3729