-40%

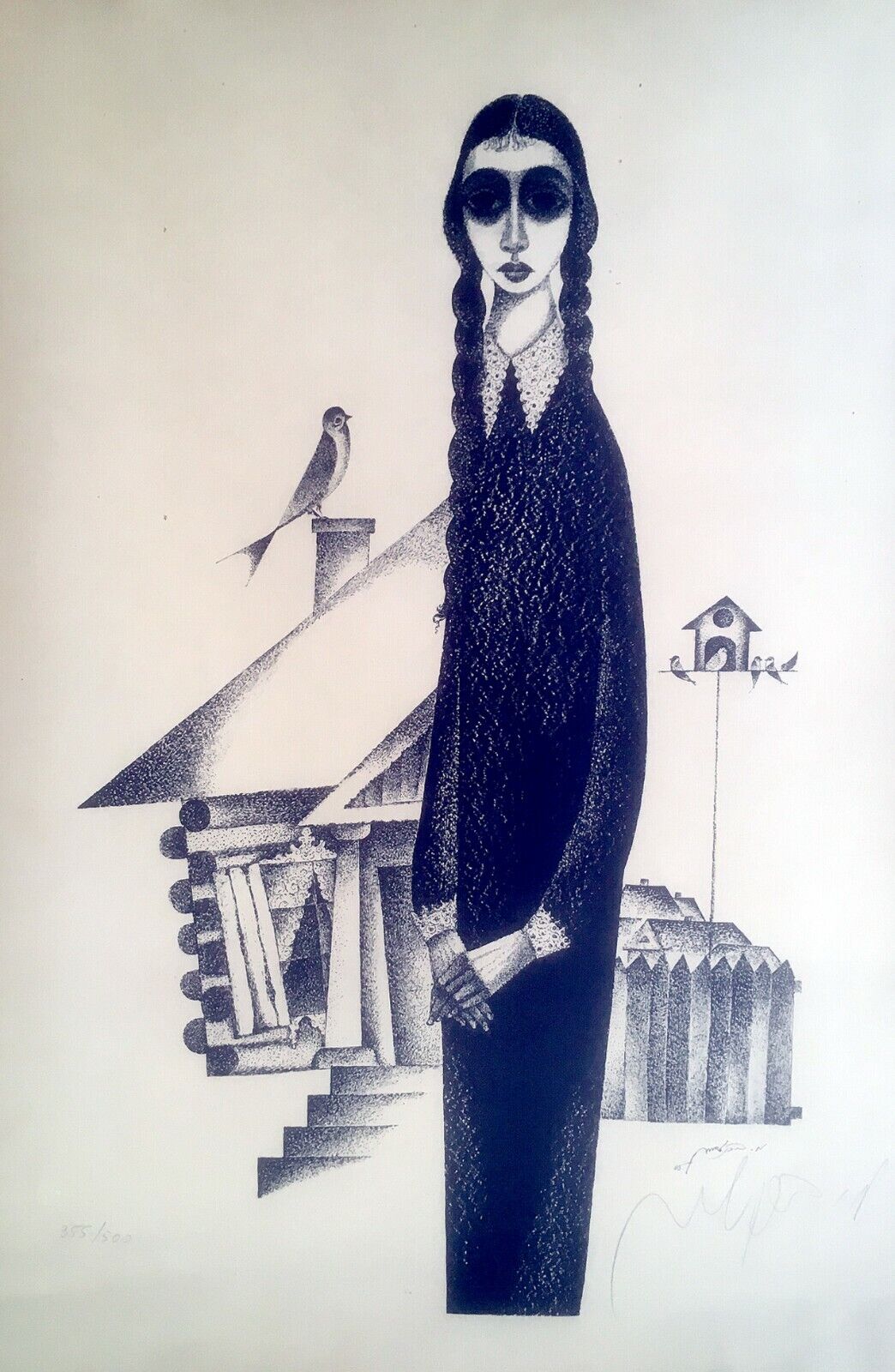

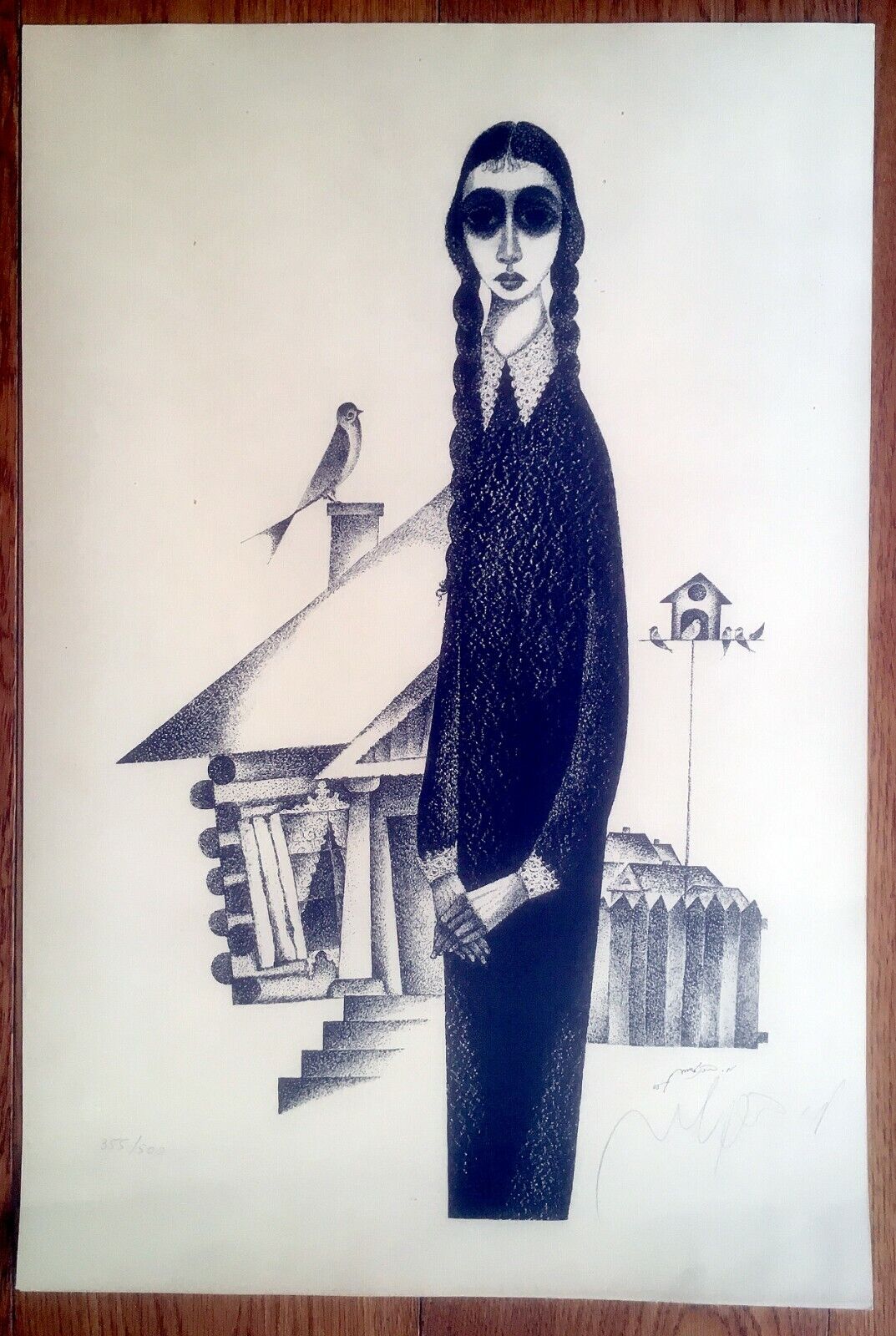

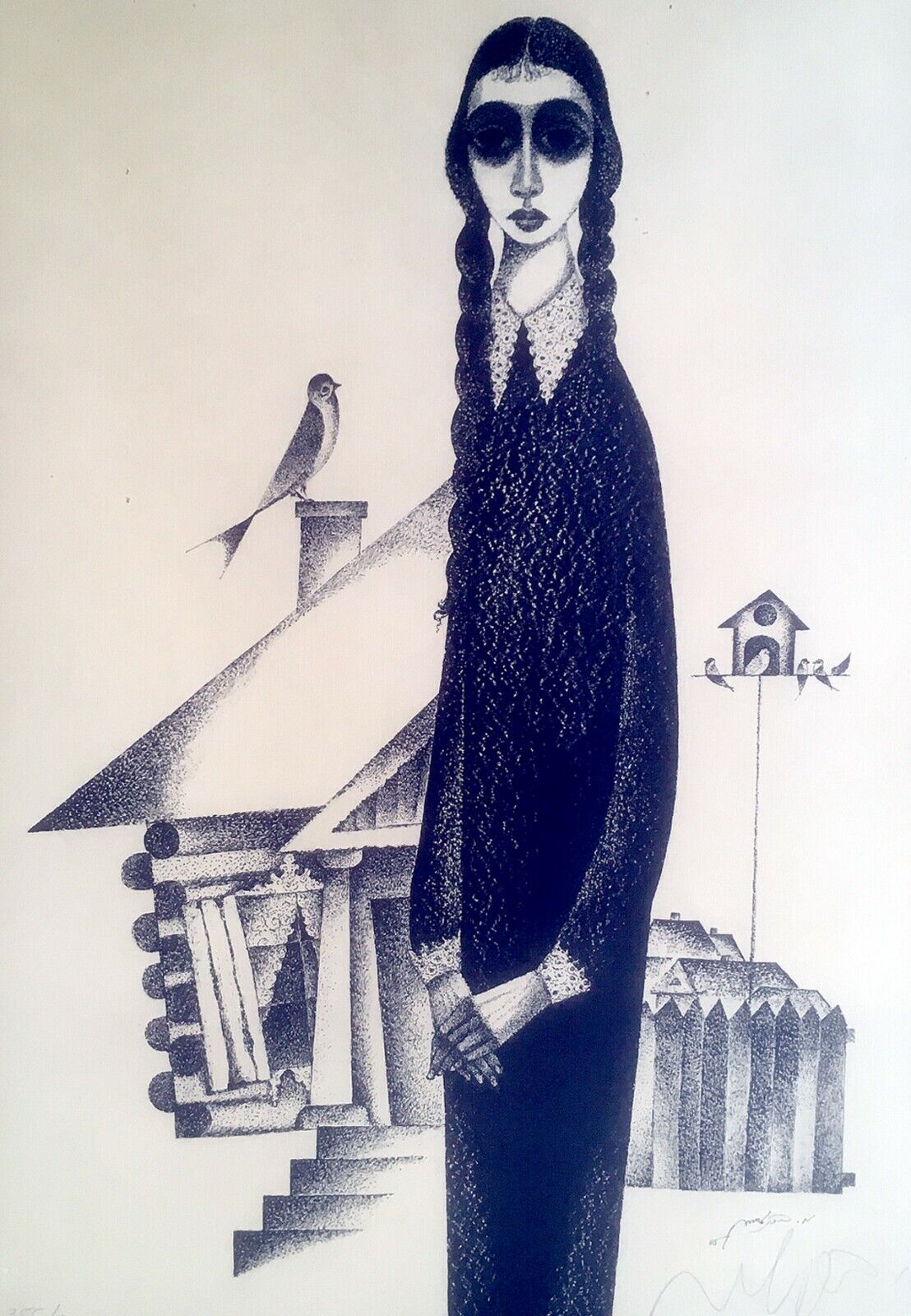

Original HAND SIGNED Jewish ART LITHOGRAPH Polish SHTETL Judaica STETL Holocaust

$ 60.72

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

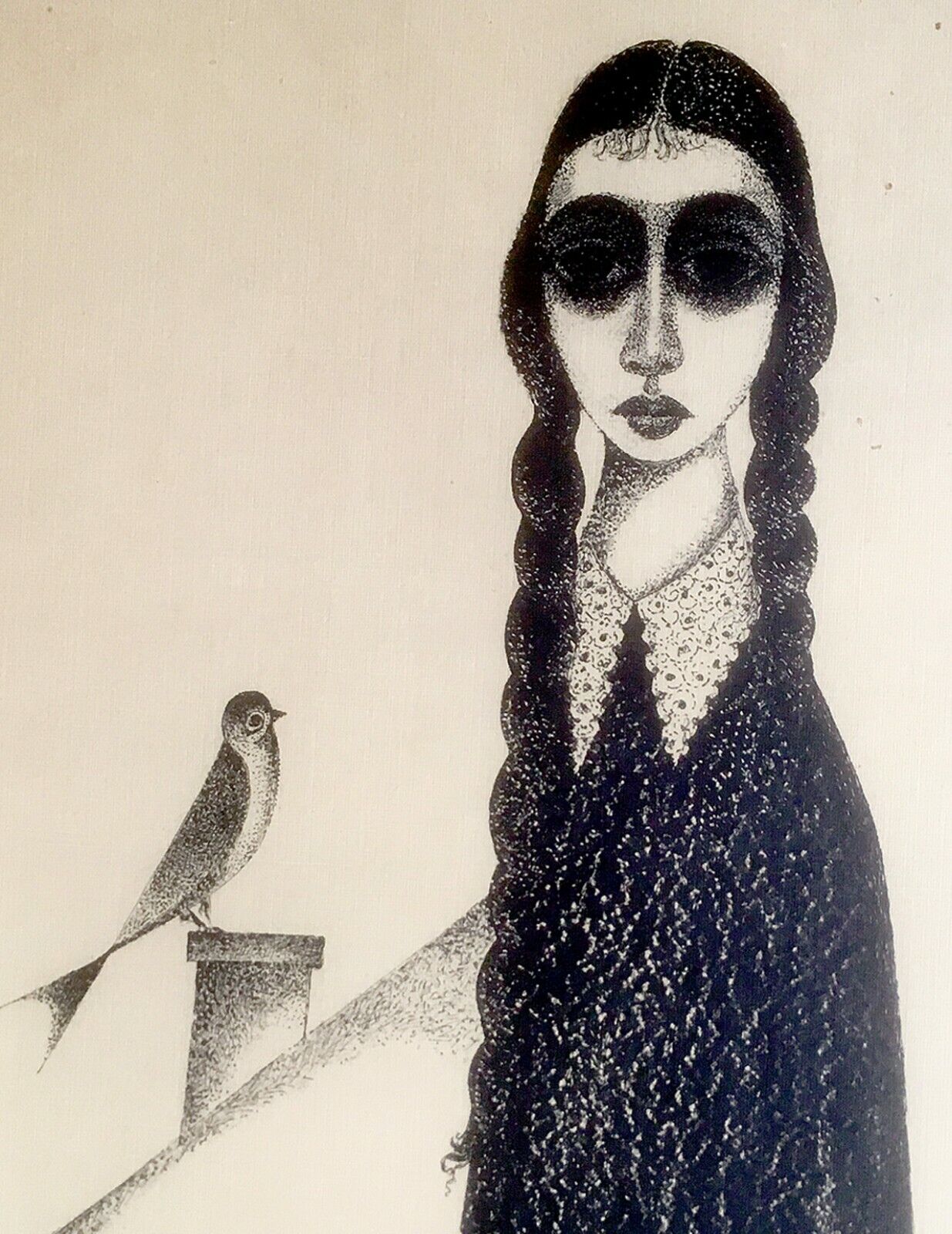

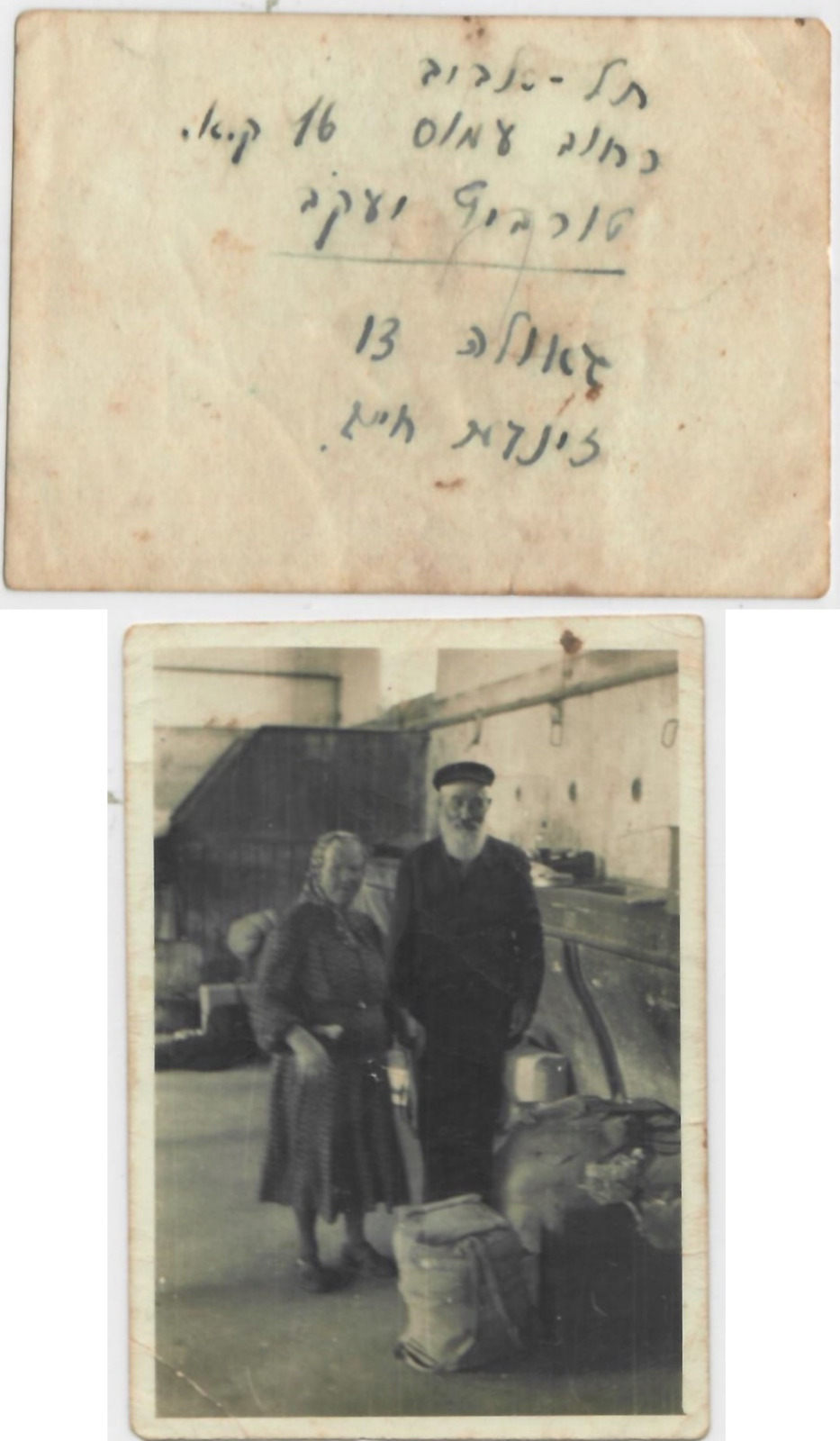

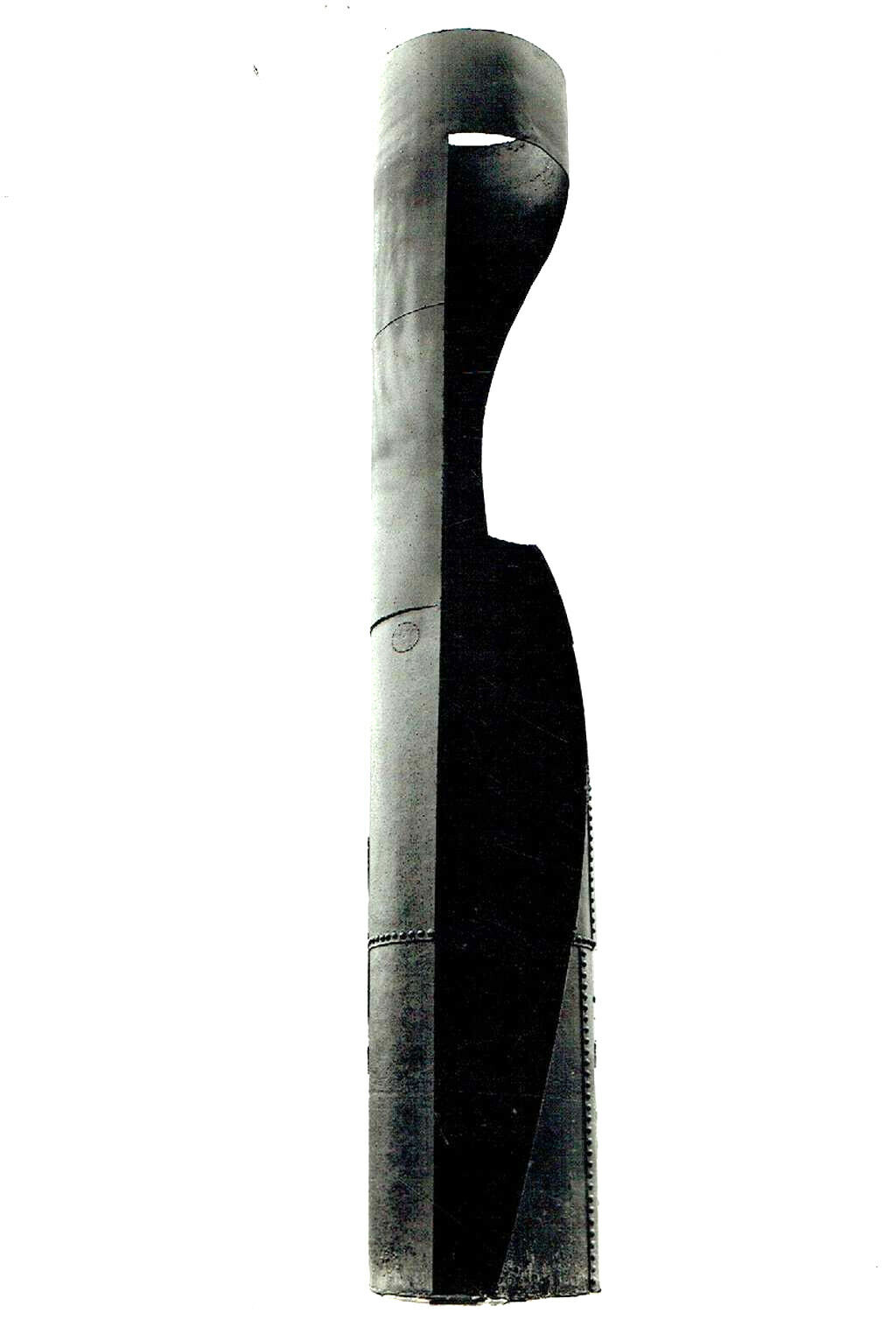

The HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR Tel Aviv POLISH-ISRAELI ARTIST Moshe BERNSTEIN has dedicated his whole JEWISH - POLISH ART to the DESTRUCTED Jewish-Yiddish SHTETL ( Stetl ) Sights, Types, Images, Famillies , Alleys and Streets . IMAGES which were perished forever after the total destruction in the HOLOCAUST. This is a magnificent example of his UNIQUE JEWISH ART. Around 60 years ago , In the 1960's, He created this

extremely delicate IMAGE of a young Jewish girl

in the Eastern European SHTETL. The MOST BEAUTIFUL and DELICATE Jewish GIRL is standing on the background of a SHTETL wooden house.

Being familliar with the artist main themes , Being the JEWISH LIFE which were destructed and demolished in the HOLOCAUST , This heart breaking image is a mourning about the

JEWISH LIFE which were destructed and demolished in the HOLOCAUST .

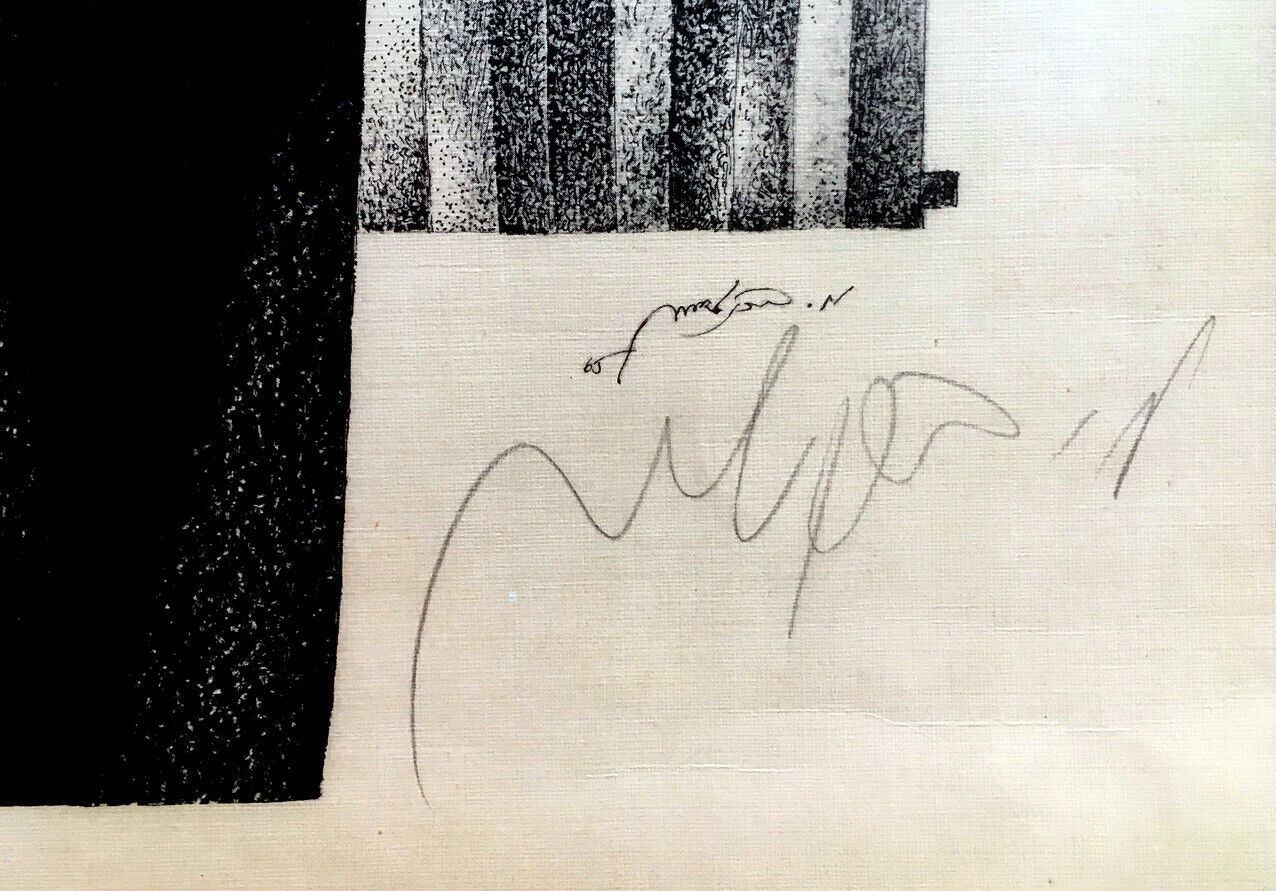

The LITHOGRAPH is HAND SIGNED with PENCIL by BERNSTEIN and numbered 350/500 . It is also signed in the plate. Size around 18" x 12" .

Very good condition.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images ) Will be sent inside a protective

tube .

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25

.

Will be sent inside a protective rigid tube

.

Will be sent around 5-10 days after payment .

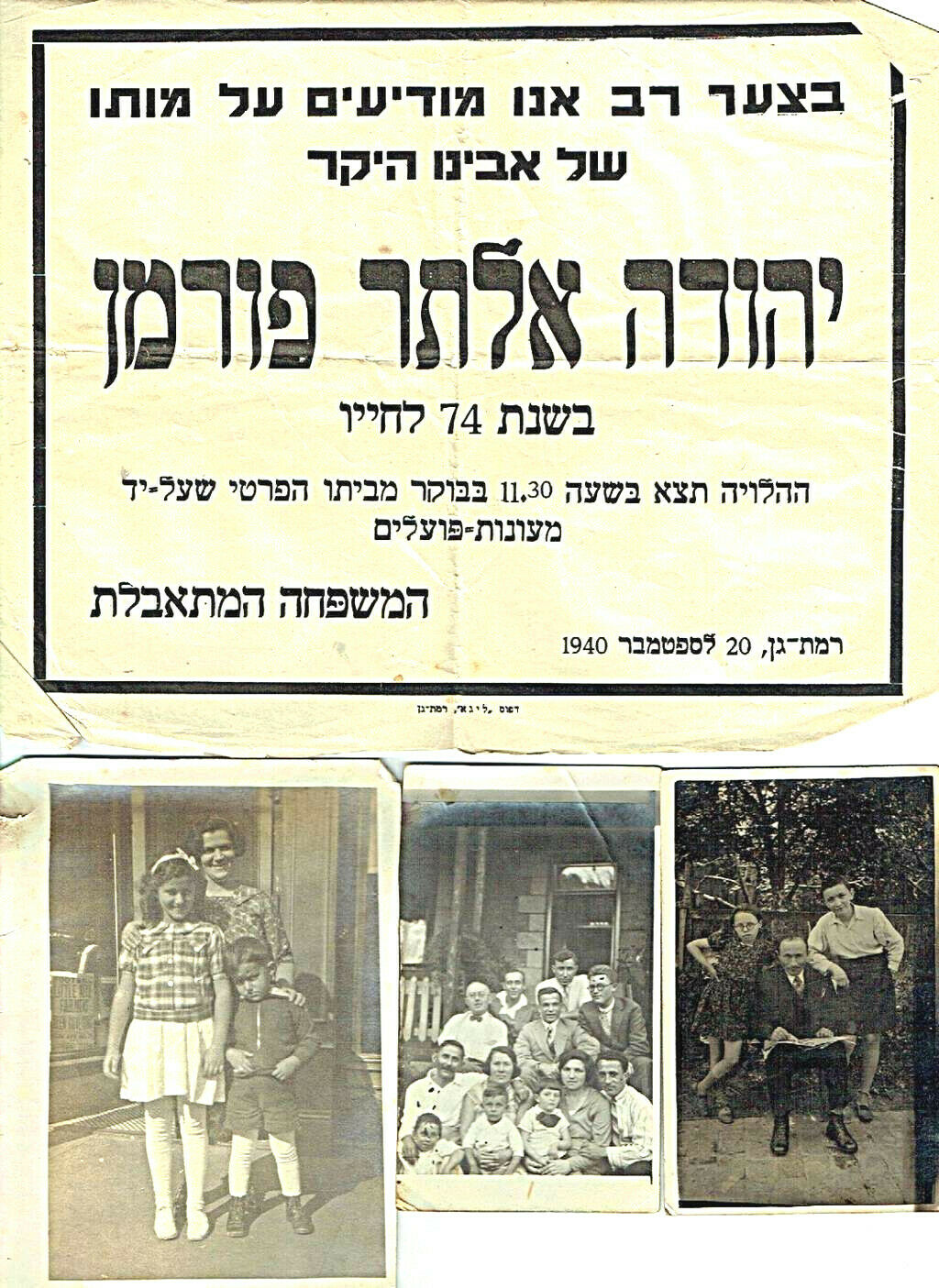

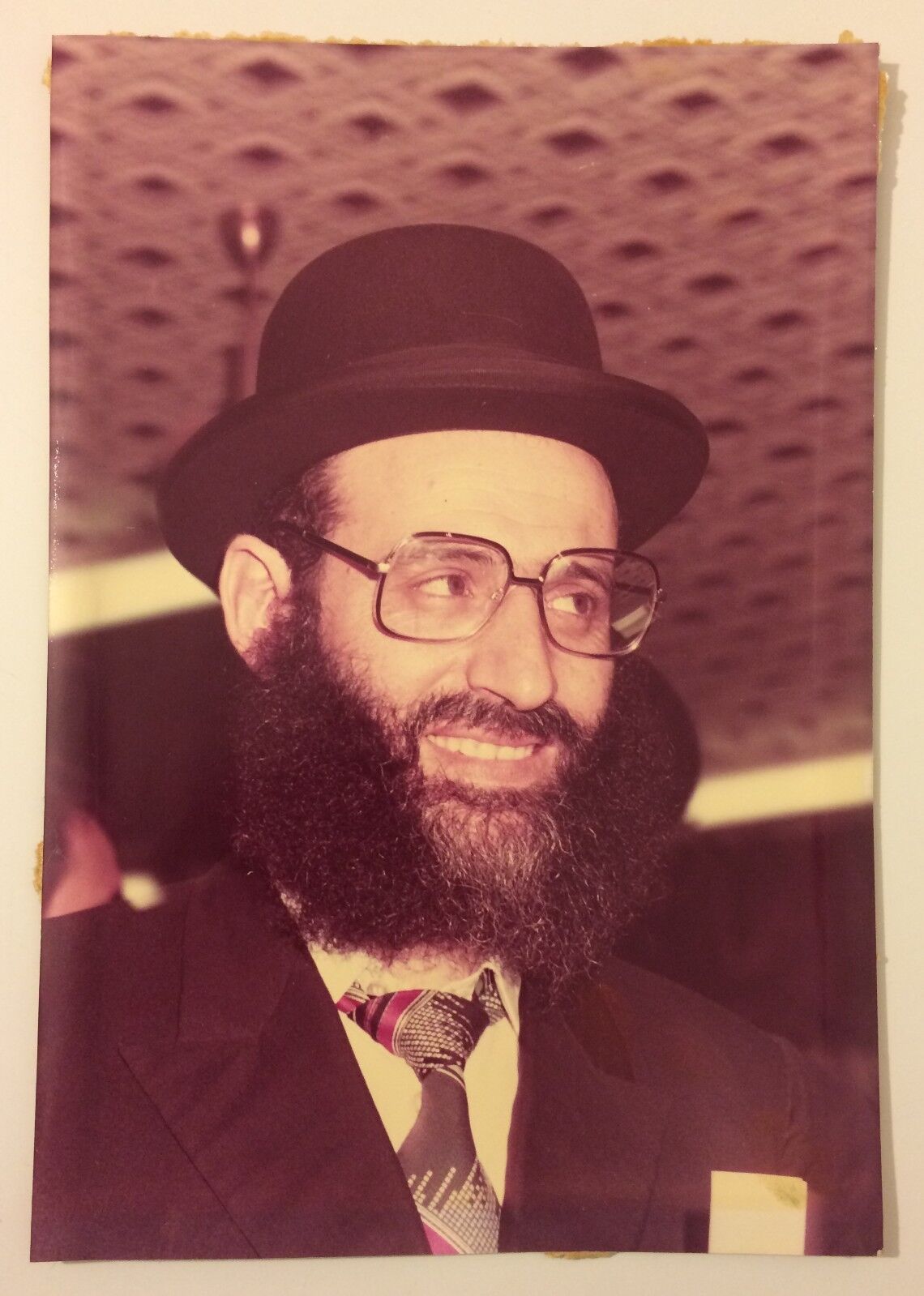

Moshe Bernstein, Israeli painter, born in Poland, 1920-2006 Moshe Bernstein was born in Bereza, Poland. He graduated from Vilna Academy of Art in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and remained in Russia until 1947, when he attempted to immigrate illegally to the Land of Israel with Aliyah Bet. He ended up in a detention camp in Cyprus, where he remained until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. He fought in the War of Independence. Bernstein's art focused on his memories from the shtetl. In 1999, the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust awarded him a prize for his "documentation of a vanished world." He also illustrated volumes of Yiddish poetry and other books. Education 1935-1939 Art Academy of Vilna 1974 sculpture under Zeev Ben Zvi in Cyprus Awards And Prizes 1980 City Medal, Tel Aviv Moshe Bernstein, Painter and Illustrator, Dies at 86 Born in Poland in 1920, Bernstein was a well-known figure in Tel Aviv's old bohemian circles and the art world. Dana Gilerman and Haaretz Correspondent Dec 11, 2006 12:00 AM 0 comments Zen Subscribe now Share share on facebook Tweet send via email reddit stumbleupon The painter Moshe Bernstein, a well-known figure in Tel Aviv's old bohemian circles and in the world of art, died late last week. He was 86. Born in Poland in 1920, Bernstein completed his art studies in the Academy of Vilna in 1939. His family was wiped out in the Holocaust, but he survived the war and lived in Russia until 1947, when he immigrated to Palestine as part of the "illegal immigration" (aliyah bet). He was caught and spent time in a detention camp in Cyprus. Bernstein's artistic path in Israel recalls that of other painters who reflected their memories of small Jewish Diaspora towns, or shtetls. At a certain stage, these artists were rejected by the local art scene. In the 1950s, '60s and '70s, the subject aroused public interest and recognition. In 1948, Bernstein participated in a group exhibit in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and in 1949 in a group exhibit at Artists' House (then known as the Artists' Pavilion). In 1954, he participated in another exhibition - of young artists - in the Tel Aviv Museum. In 1962, he had a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum, another in 1967 at the Haifa Museum, and a retrospective in 1973 in the Ein Harod Museum of Art. Interspersed among these events were shows at the Katz and Chemerinsky Galleries in Tel Aviv. A Bernstein exhibit, which included paintings of the shtetl, was shown in 1998 at the international theater festival in Parma, Italy. In 1999, he was awarded a prize by the Massuah Institute for the Study of the Holocaust, for his "documentation of the world that vanished at the beginning of his career." His paintings appeared on the walls of the defunct Kassit cafe in Tel Aviv, and in the Kiton restaurant - "places in which he ate and gave paintings," says gallery owner Zaki Rosenfeld, whose father, Eliezer Rosenfeld, worked with Bernstein. Bernstein's paintings always touched on memories of the Jewish town he was forced to leave at a young age. They were a constant reminder of the destruction of European Jewry, but also expressed great yearning. Bernstein wrote in the catalogue of the 1973 exhibition in Ein Harod: "In this exhibition, I once again bring you the experiences and dreams of my longed-for past, because for me it is an enchanted garden which I walk as if intoxicated by its fragrances and its beauty, and from which I draw the inspiration for my work." "Moshe was one of those young artists who gave expression to a different kind of experience in that period," says Galia Bar-Or, curator and director of the Ein Harod Museum of Art. "He is perceived as the kind of Jewish artist that gives sentimental expression to the memory of a Jewish culture that is gone forever. He also illustrated books of Yiddish poetry. He did the typography by hand, in black ink; and in his decorations around the sides there appeared that same figure of a Jewish girl, with a black braid and big eyes, and the houses of the town." Keep updated: Sign up to our newsletter Email* Sign up At a certain stage he began to concentrate increasingly on graphic art. Among others, he illustrated Israel Ch. Biletzky's book, "A Jewish Shtetl," which was published in 1986. "My father, who also came from the shtetl, worked with him for years, and loved his work," says Zaki Rosenfeld about Bernstein. "He belonged to that same vanishing group of artists who represented and preserved the cultural fabric from which they themselves came. When I turned the gallery into a gallery of contemporary art, he would walk down Dizengoff Street, look at the gallery, spit on the ground, make sure I had seen him, and continue on his way. There is no doubt that the face of this little man, and what he represented, will be missed on the Tel Aviv landscape."**** A shtetl (Yiddish: שטעטל, diminutive form of Yiddish shtot שטאָט, "town", pronounced very similarly to the South German diminutive "Städtle", "little town"; cf. MHG: stetelîn, stetlîn, stetel) was typically a small town with a large Jewish population in pre-Holocaust Central and Eastern Europe. Shtetls (Yiddish plural: שטעטלעך, shtetlekh) were mainly found in the areas which constituted the 19th century Pale of Settlement in the Russian Empire, the Congress Kingdom of Poland, Galicia, and Romania. A larger city, like Lemberg or Czernowitz, was called a shtot (Yiddish: שטאָט); a smaller village was called a dorf (Yiddish: דאָרף). The concept of shtetl culture is used as a metaphor for the traditional way of life of 19th-century Eastern European Jews. Shtetls are portrayed as pious communities following Orthodox Judaism, socially stable and unchanging despite outside influence or attacks. The Holocaust resulted in the disappearance of the vast majority of shtetls, through both extermination and mass exodus to the United States and what would become Israel. Origins The history of the oldest Eastern European shtetls began about a millennium ago and saw periods of relative tolerance and prosperity as well as times of extreme poverty, hardships and pogroms. The attitudes and thought habits characteristic of the learning tradition are as evident in the street and market place as the yeshiva. The popular picture of the Jew in Eastern Europe, held by Jew and Gentile alike, is true to the Talmudic tradition. The picture includes the tendency to examine, analyze and re-analyze, to seek meanings behind meanings and for implications and secondary consequences. It includes also a dependence on deductive logic as a basis for practical conclusions and actions. In life, as in the Torah, it is assumed that everything has deeper and secondary meanings, which must be probed. All subjects have implications and ramifications. Moreover, the person who makes a statement must have a reason, and this too must be probed. Often a comment will evoke an answer to the assumed reason behind it or to the meaning believed to lie beneath it, or to the remote consequences to which it leads. The process that produces such a response-- often with lightning speed-- is a modest reproduction of the pilpul process.[1] Not only did the Jews of the shtetl speak a unique language (Yiddish), but they also had a unique rhetorical style, rooted in traditions of Talmudic learning: In keeping with his own conception of contradictory reality, the man of the shtetl is noted both for volubility and for laconic, allusive speech. Both pictures are true, and both are characteristic of the yeshiva as well as the market places. When the scholar converses with his intellectual peers, incomplete sentences a hint, a gesture, may replace a whole paragraph. The listener is expected to understand the full meaning on the basis of a word or even a sound... Such a conversation, prolonged and animated, may be as incomprehensible to the uninitiated as if the excited discussants were talking in tongues. The same verbal economy may be found in domestic or business circles.[1] The shtetl operates on a communal spirit where giving to the needy is not only admired, but expected and essential: The problems of those who need help are accepted as a responsibility both of the community and of the individual. They will be met either by the community acting as a group, or by the community acting through an individual who identifies the collective responsibility as his own... The rewards for benefaction are manifold and are to be reaped both in this life and in the life to come. On earth, the prestige value of good deeds is second only to that of learning. It is chiefly through the benefactions it makes possible that money can "buy" status and esteem.[1] This approach to good deeds finds its roots in Jewish religious views, summarized in Pirkei Avot by Shimon Hatzaddik's "three pillars": On three things the world stands. On Torah, On service [of God], And on acts of human kindness.[2] Tzedaka (charity) is a key element of Jewish culture, both secular and religious, to this day. It exists not only as a material tradition (e.g tzedaka boxes), but also immaterially, as an ethos of compassion and activism for those in need. Material things were neither disdained nor extremely praised in the shtetl. Learning and education were the ultimate measures of worth in the eyes of the community, while money was secondary to status. Menial labor was generally looked down upon as prost, or prole. Even the poorer classes in the shtetl tended to work in jobs that required the use of skills, such as shoe-making or tailoring of clothes. The shtetl had a consistent work ethic which valued hard work and frowned upon laziness. Studying, of course, was considered the most valuable and hard work of all. Learned yeshiva men who did not provide bread and relied on their wives for money were not frowned upon but praised as ideal Jews. Interaction with Gentiles The shtetl's main interaction with Gentile citizens was in trading with the neighboring peasants. There was often animosity towards the Jews from these peasants, resulting in extremely violent pogroms from the Gentiles on the Jews, resulting in many Jewish deaths[when?][where?][who?]. This, among other things, helped foster a very strong "us-them" mentality based on differences between the peoples[vague]. This can be seen in the play Fiddler on the Roof[unreliable source?]. Collapse The May Laws introduced by Tsar Alexander III of Russia in 1882 banned Jews from rural areas and towns of fewer than ten thousand people. In the 20th century revolutions, civil wars, industrialization and the Holocaust destroyed traditional shtetl existence. However, Hasidic Jews have founded new communities in the United States, such as Kiryas Joel and New Square. There is a belief found in historical and literary writings that the shtetl disintegrated before it was destroyed during World War II; however, this alleged cultural break-up is never clearly defined.[who?][3] The shtetl in fiction and folklore Chełm figures prominently in the Jewish humor as the legendary town of fools. Kasrilevke, the setting of many of Sholom Aleichem's stories, and Anatevka, the setting of the musical Fiddler on the Roof (based on other stories of Sholom Aleichem) are other notable fictional shtetls. The 2002 novel Everything Is Illuminated, by Jonathan Safran Foer, tells a fictional story set in the Ukrainian shtetl Trachimbrod. (Trochenbrod) The 1992 children's book Something from Nothing, written and illustrated by Phoebe Gilman, is an adaptation of a traditional Jewish folktale set in a fictional shtetl. In 1996 the Frontline programme Shtetl broadcast; it was about Polish Christian and Jewish relations ******

ebay4873 folder 179