-40%

Original HAND SIGNED Limited JEWISH SERIGRAPH PAPERCUT Judaica SHADUR Jerusalem

$ 29.04

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

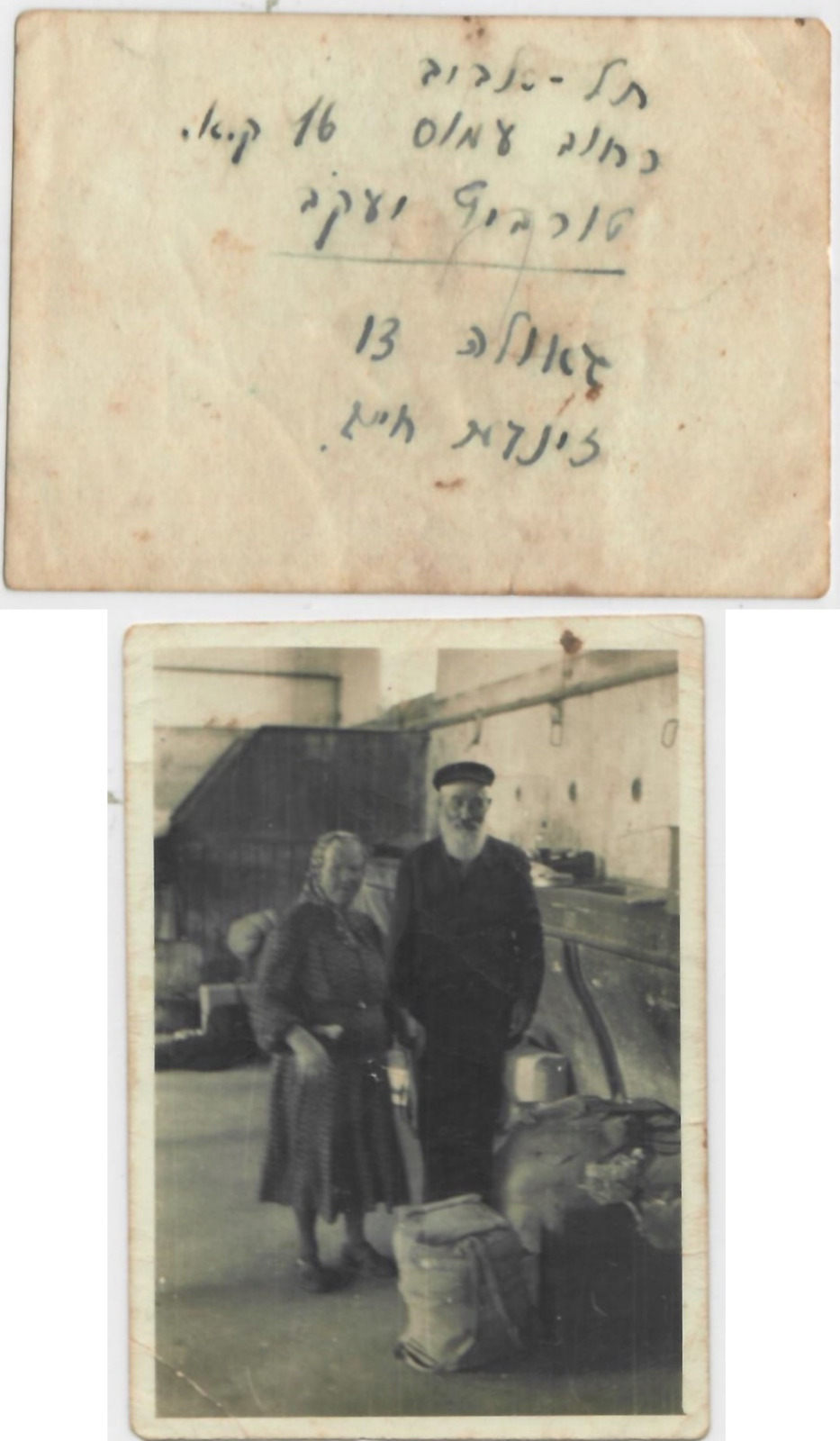

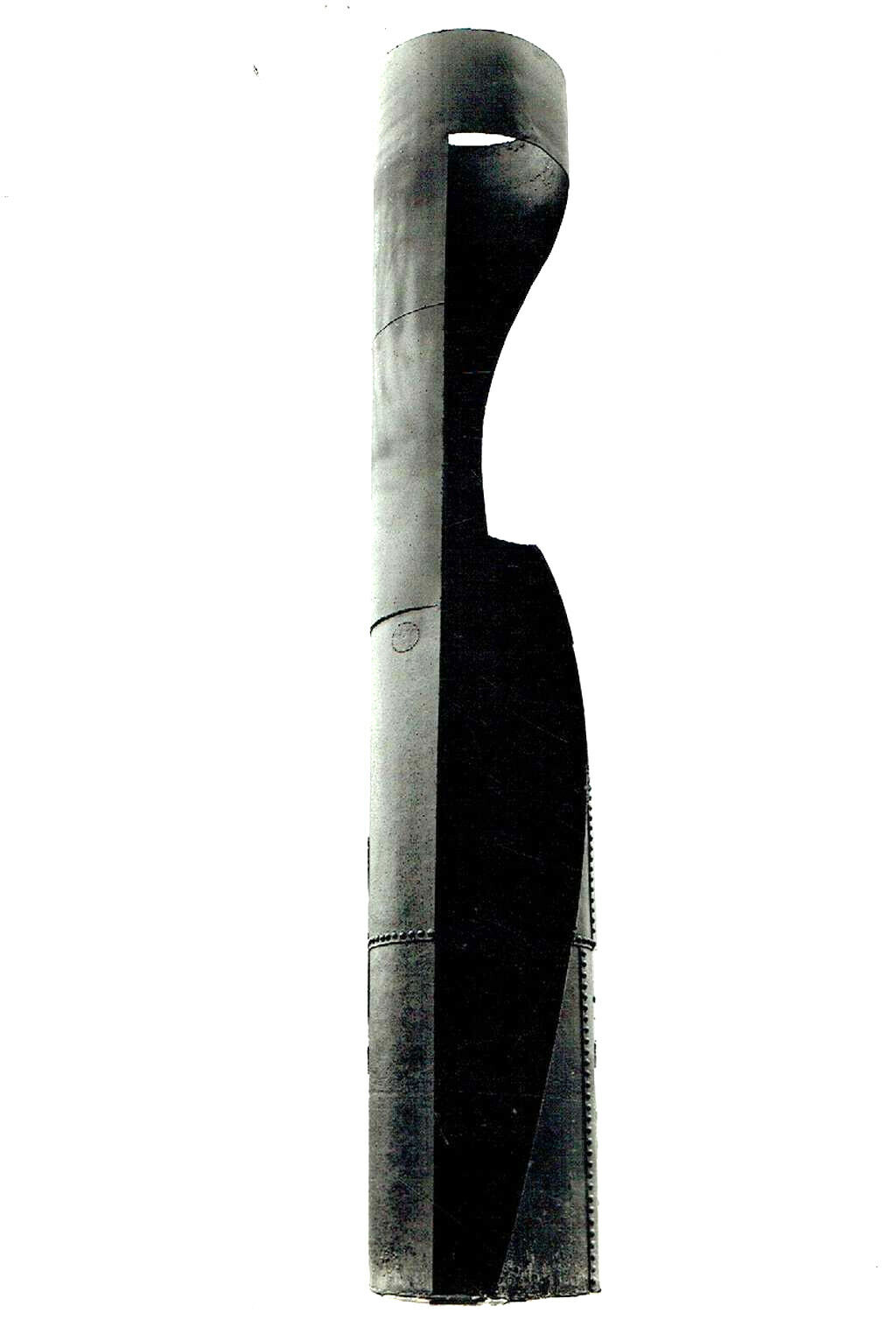

Here for sale is an

exquisit ART PIECE , Being a LIMITED HAND SIGNED SERIGRAPH greeting card , Based on an ORIGINAL JEWISH PAPERCUT of the world acclaimed PAPERCUT MASTER from Jerusalem Israel YEHUDIT SHADUR . The PIECE is a colored PAPERCUT of the Biblical phrase "LOVE THY NEIGHBOR" accompanied by MAGNIFICENT PAPERCUT DECORATIONS and the Hebrew TRADITIONAL verse. The colorful JEWISH PAPERCUT was printed ca 1970's as a SERIGRAPH on Fabriano paper , HAND SIGNED in HEBREW and ENGLISH by the ARTIST . Serigraph sheet size around 5" x 7". Folded. Excellent condition.

( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )

.

Will be shipped in a special protective rigid sealed packaging.

AUTHENTICITY

: This is an ORIGINAL ca 1970's hand signed piece , NOT a reproduction or a reprint , It holds a life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:

SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is .

Will be shipped in a special protective rigid sealed packaging.

Handling around 5 days after payment.

Yehudit Shadur of Jerusalem is one of the foremost contemporary artists working in the field of Jewish decorative arts. She is particularly known for pioneering the revival of the Jewish papercutting tradition. Her work is represented in major museums and Judaica collections in Europe, North America, and Israel, including the Israel Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Library of Congress, and the Schweizerisches Museum in Basel. Yehudit Shadur’s paper-cuts may be purchased in two forms, originals and serigraphs. Serigraphs are prints made in limited editions of about 200 copies. Each serigraph is printed in color on fine, heavy quality Fabriano Rosapina print paper and is signed and numbered by the artist. The making of devotional papercuts is a relatively little-known aspect of traditional Jewish folk art and culture. While many ritual objects treasured today as "Judaica" were crafted from expensive materials, often by gentile artisans executing paid commissions, even the poorest Jew could afford paper, pencil, and penknife with which to make a papercut as a deeply-felt, personal expression of faith. Many of these works are gems of unaffected artistic creation. More than any other form of Jewish art, the surviving old Jewish papercuts evoke the spirit and lore of the East-European shtetl and the North African mellah. By the mid-20th century, however, the venerable Jewish papercutting tradition had become another lost folk art. This lavishly illustrated, full-color volume features many Jewish papercuts from Eastern and Central Europe reproduced here for the first time. These, and such works from Middle Eastern, North African, and North American Jewish communities incorporate an unparalleled wealth of Jewish symbols. Joseph and Yehudit Shadur's discussions of these configurations constitute a basic presentation of Jewish iconography of the last three centuries. The culmination of over twenty-five years of their searches and research on four continents, Traditional Jewish Papercuts is the definitive work on the subject. The Shadurs' initial, profusely-illustrated, Jewish Papercuts: A History and Guide, published in 1994, won the annual National Jewish Book Council Award for the outstanding book in the visual arts. Their present work, Traditional Jewish Papercuts: An Inner World of Art and Symbol, offers readers much new material, insights, and interpretations, with detailed chapters on sources, typologies, and techniques. A special chapter deals with modern imitations and fraudulent works aimed at the collectors' market. An expanded, selective bibliography and an index are appended. Jewish paper cutting is a traditional form of Jewish folk art made by cutting figures and sentences in paper or parchment. It is connected with various customs and ceremonies, and associated with holidays and family life. Paper cuts often decorated ketubbot (marriage contracts), Mizrahs, and ornaments for festive occasions. Paper cutting was practiced by Jewish communities in both Eastern Europe and North Africa and the Middle East for centuries and has seen a revival in modern times in Israel and elsewhere.The origin of Jewish paper cutting is unclear. European Jews in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries practiced this type of art. However, Jewish paper cuts can be traced to Jewish communities in Syria, Iraq, and North Africa, and the similarity in the cutting techniques (using a knife) between East European Jews and Chinese paper cutters, may indicate that the origin goes back even further.The first mention of Jewish paper cutting can be found in the treatise "The fight of the pen and the scissors” by a 15th-century rabbi, Shem Tov ben Isaac ben Ardutiel, who describes how he decided to cut letters in paper when his ink became frozen during a harsh winter. Paper cutting as a folk craft gained popularity in the nineteenth century when paper became a cheap material.[1] It was considered a unique art form, and was "created by mostly anonymous folk artists."[2]Paper cutting was widespread among the Jews of Poland and Russia in the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth century. Jewish paper cuts were also produced in Germany and probably in the Netherlands. Some Italian Jewish parchment ketubot (marriage contracts) from the late 17th century until the nineteenth century were decorated paper cuts as well as some elaborate scrolls of the Book of Esther. Similar paper cuttings from Jewish communities North Africa and the Middle East have some characteristic style differences.It was popular among Jews both in eastern and western Europe as well as in Turkey, Morocco, Syria, Bangladesh, Israel, and North America.[3]In North Africa and the Middle East paper cuts were called a "Menorah", because one or more menorah, always appeared as the central motif. These paper cuts included many inscriptions, mostly on the arms of the candelabras. The paper was mounted on thin, colored metal sheets. Two distinct kinds were produced: a Mizrah and smaller paper cuts used as charms. The motifs are the same as in European Jewish paper cuts but they have a distinctive Eastern style. Also, the hamsa ("the five-finger hand"), unknown in Europe, very often appears on these paper cuts.DisappearanceJewish paper cutting began disappearing in the first half of the twentieth century, mainly because of the rapid assimilation trends and the waning of many traditional practices, and was practiced only by older people who remembered this art form from their youth. Many paper cuts collections that had been preserved were destroyed during World War II and the Holocaust and relatively few remain in public or private collections.ResurgenceSince the late twentieth century, Jewish paper cuts have again become a popular art form in both Israel and other countries. Paper cutting is again often used to decorate ketubot, wedding invitations, and works of art. To a limited extent, Jewish paper cuts have become more popular in Poland as a result of the Jewish Culture Festival in Kraków, a festival that has been held in Kraków since the 1990s.Beit Hatefutsot: The Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, Israel presented a 2009 exhibition called "The Revival of Jewish Papercuts: Jewish paper cut art" in October 2009. The exhibit was curated by Prof. Olga Goldberg, Gabriella Rabbi, Rina Biran, the Giza Frenkel Papercut Archive, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Additionally, a National Science Foundation-funded study called “Tradition and Continuity in Jewish Papercuts” was conducted by Prof. Olga Goldberg.[4]Today, Jewish papercut art has grown in popularity beyond ritual items to art and expressions of Jewish faith, not only in Israel but worldwide.ArtistsGiza FrankelIn Israel papercutting was reactivated by Giza Frankel, a Polish-born ethnographer.[5] Frankel's most significant publications on paper cutting are Wycinanka żydowska w Polsce and Art of the Jewishpaper-cut.[6] Giza Frankel brought Polish paper cuts when she emigrated to Israel in 1950.[7]According to Frankel, the most famous Polish papercutters are Marta Gołąb and Monika Krajewska.Marta GołąbMarta Gołąb is both a graphic artist and papercutter.[8] Her papercuts were exhibited in the Jewish Museum (Wien) Skirball Cultural Center, (Los Angeles), in Emanu-El Synagogue (San Francisco), in the Synagogue in Grobzig (Germany) and on the Jewish Culture Festival in KrakowMonika KrajewskaMonika Krajewska's interests was focus on symbols related both to Jewish papercut and sepulchral art, according to Wycinanka żydowska. She is a member of The Guild of American Papercuters.[9]Joseph and Yehudit ShadurJoseph and Yehudit Shadur,[10] in addition to being Jewish paper cutting artists,[11] wrote a history of the last three centuries of Jewish paper cutting called Traditional Jewish Papercuts: An Inner World of Art and Symbol. They won a 1994 Jewish National Book Council prize[12] for their work.[13][14]Tsirl WaletzkyTsirl Waletzky (née Tsirl Grobla) was considered to be a major contemporary paper cutting artist in American Yiddish culture.[15] Waletzky’s papercuts differed from "traditional forms in that they are free flowing and less bound to structure and symmetry."[16]Kim PhillipsKim Phillips is a modern Jewish paper cut artist whose work pushes the limits of interpretation of Jewish texts and themes without reference to traditional symmetrical forms. Her work has been exhibited in Israel and in the United States.UsesTypesDepending on their purpose, shape and connection with specific religious and non-religious events, paper cuts are of different types.[17]:40-57A Mizrah (hebr. The East) is a plaque hung on the east wall of private houses to show the direction of Jerusalem. A shivis’i (hebr. always) is similar to a mizrah, but it hangs on the east side of a synagogue. Its name is connected with a sentence from the Bible: 'Shivis'I adonai l'negdi tamid' ('I have set the LORD always before me').[17]:4 Shivis’i in the form of paper cuts rather than some more durable material were only used in poor synagogues.There were also various paper cuts made for special, religious celebrations. Shevuoslakh and Royzalakh decorated windows for Shavuot. Shevuoslakh are circle-shaped paper cuts, while Rojzalakh are rectangular. They were often made by pupils in elementary Jewish religious schools (Cheders). They were sometimes decorated with motifs unconnected to religion, such as soldiers or riders.Flags for Simchat-Torah were also made by cheder pupils. Created from colourful paper, each paper cut symbolized one of the twelve tribes of Israel. The other side of the paper showed an image of Torah with moving doors cut in paper. Paper cuts made for Sukkot were formed into lanterns, chains and birds, hung in Sukkahs.Paper cuts often decorated a plaque with a prayer called Ushpizin, made for Sukkot. Paper cuts were also created for Purim, often containing the Hebrew sentence: ”Mishenekhnas adar marbin b’simcha’ (‘We should rejoice because (the month of) Adar begins') and cut into an image of a bottle and glasses, a symbol of rejoicing.[17]:11Papercutting also has connections with other forms of Jewish tradition. For example, Ketubahs (marriage agreements) were sometimes prepared in the form of paper cut. Also cut into paper, memorial plaques were made to commemorate the names of ancestors’ names and dates of birth and death. Lanterns with papercut walls were placed in synagogues for anniversaries of great men’s death.[17]:10-11 Amulets like a Hamsa often showed an image of a palm with an eye on it.CharacteristicsFeaturesPaper cuts traditionally were created with the use of shoemaker’s knife. Only men could create then. In exception, girls in school made little rosettes with scissors to decorate their notebooks. Paper cutters first drew the pattern on a paper or parchment and then cut it. Sometimes, they painted their work in watercolors. Paper cuts were usually glued to a contrasting background in a specific way, to throw a shadow on it. Hebrew sentences were important element of the composition. They were either cut or drew on a paper. Because of the religious ban, no pictures of people were put on the paper cuts. Exceptions are Sephardic Ketubas with an image of a bride and a bridegroom.[3]StylesTraditionally, paper cuts made by Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews differed from each other. Ashkenazi papercuts were rich, various and colorful. The characteristic feature of the composition washorror vacui (in Latin: ‘A fear of the void’). In this style, artists tried to fill the free space with as many elements as is possible. By contrast, the Sephardic compositions were less “overloaded.” The main elements were limited to menorah, columns, oriental arcs and lanterns.[3] Modern Jewish paper cut art is done in many styles and is not limited to traditional Jewish symbols. They may be single-layered or multi-layered.SymbolsEvery element of Jewish paper cut has its own symbolism. Some are typical of general Jewish culture, others are peculiar to the art of paper cutting. The most important symbols are placed along the axis of symmetry.The main symbols are usually a Torah or a Menorah:The image of the Torah symbolizes God’s law, Judaism, Israel. The Star of David symbolizes Judaism and IsraelThe Menorah symbolizes Israel, Judaism, and Temple in Jerusalem. The middle flame is a symbol of ‘Shekinah’ (Hebrew for God’s presence); the other flames are shown as leaning towards the main flame. The bottom of the menorah is often shown as a complicated ornament symbolizing infinityA range of animals are depicted in paper cuts:Lions, a biblical symbol of the Tribe of Judah, are associated with strength, bravery, power[18]Deer symbolize the Tribe of Naphtali[17]:6[19]Birds are associated with the human soulFish are usually connected with fertilityA squirrel biting a nut symbolizes the effort put into reading the TorahThe Four Animals (a leopard, an eagle, a gazelle, and a lion) are connected with a sentence from Pirkei Avot: “Be strong as the leopard, swift as the eagle, fleet as the gazelle, and brave as the lion to do the will of your Father in Heaven”[20]A snake eating its own tail symbolizes infinity[3]Papercut flora is usually connected with the biblical Tree of Life,[17]:6 with some of the plants having their specific symbolism. For example, vine was associated with the land of Israel and with fertility, pomegranates symbolized fertility, etc.Others symbols were connected both with tradition and with everyday life:Signs of the Zodiac showed the sequence of Jewish celebrations during the yearOften positioned above the Torah or a Menorah, the crown is a symbol of God, the Torah, the Kingdom of Israel or the Priesthood[17]:5Columns and other architectonic elements are associated with the Temple in JerusalemHands with joined thumbs are a gesture of blessingA jug filled with water and a bowl symbolize the Tribe of Levi, blessing or the PriesthoodMethodologyThe traditional method of making paper cuts was "cutting a folded piece of paper to produce a symmetrical design once the sheet is opened."[21] Today, some papercut artists use scissors; others use a craft knife.Works or publicationsBooksBłachowski, A. (1986). Polska wycinanka ludowa. Toruń: Muzeum Etnograficzne, pp. 12–14.Frankel, G., & Har'el-Hoshen, S. (1983). Migzerot neyar: Omanut Yehudit 'amamit. Ramat-Gan: Masadah.Fränklowa, G. (1929). Wycinanka zydowska w Polsce: (Papierschnitte bei den Juden in Polen). Lwów: Nakł Towarzystwa Ludoznawczego.Shadur, J., & Shadur, Y. (1994). Jewish papercuts: A history and guide. Berkeley, Calif: Judah L. Magnes Museum (JLMM) Jerusalem. ISBN 9780943376547Shadur, Y., & Judah L. Magnes Memorial Museum. (1978). Paper-cuts by Yehudit Shadur: (March 12-May 7, 1978 exhibition.) Magnes Museum. Berkeley, Calif.: Magnes Museum.Shadur, J., & Shadur, Y. (2002). Traditional Jewish papercuts: An inner world of art and symbol. Hanover: University Press of New England. Google Books (includes images) ISBN 9781584651659Shadur, Y., & Muzeʼon Erets-Yiśraʼel (Tel Aviv, Israel). (1996). Yerushalayim le-dor ṿa-dor: Mi-gizrot neyar. (Catalog of an exhibition held at Muzeʼon Erets Yiśraʼel as part of "Jerusalem 3000" celebration, winter 1995/96.) Tel-Aviv: Muzeʼon Erets-Yiśraʼel.Waletzky, T. The Magic of Tsirl Waletzky. Photography by Elaine Liebenbaum.Waletzky, T., & Hebrew Home for the Aged at Riverdale. (1988). Contemporary paper cuts. (January 10-June 26, 1988 exhibition.) New York: Judaica Museum.Waletzky, T., & Yeshiva University. (1977). Papercuts: A contemporary interpretation. (1977 exhibition: "The Story of Ruth.") New York: Yeshiva University Museum.Online imagesMizrah by Israel Dov Rosenbaum. Podkamen, Ukraine, 1877 (date of inscription). Paint, ink, and pencil on cut-out paper. 30 1/4 x 20 3/4 in. (76.8 x 52.7 cm). The Jewish Museum, New York.Mizrah/Shiviti by Mordecai Reicher (American, b. Ukraine, 1865-1927). Brooklyn, New York, United States, 1921/22. Ink and watercolor on cut-out paper. 19 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. (50.2 x 40 cm). The Jewish Museum, New York.Memorial Calendar, Shiviti, and Mizrah by Hayyim Benjamin Blum, Mordecai Abraham. Poland, 19th century. Paint, pencil, and collage on cut-out paper. 21 7/8 x 21 3/4 in. (55.6 x 55.2 cm). The Jewish Museum, New York. EBAY2989