-40%

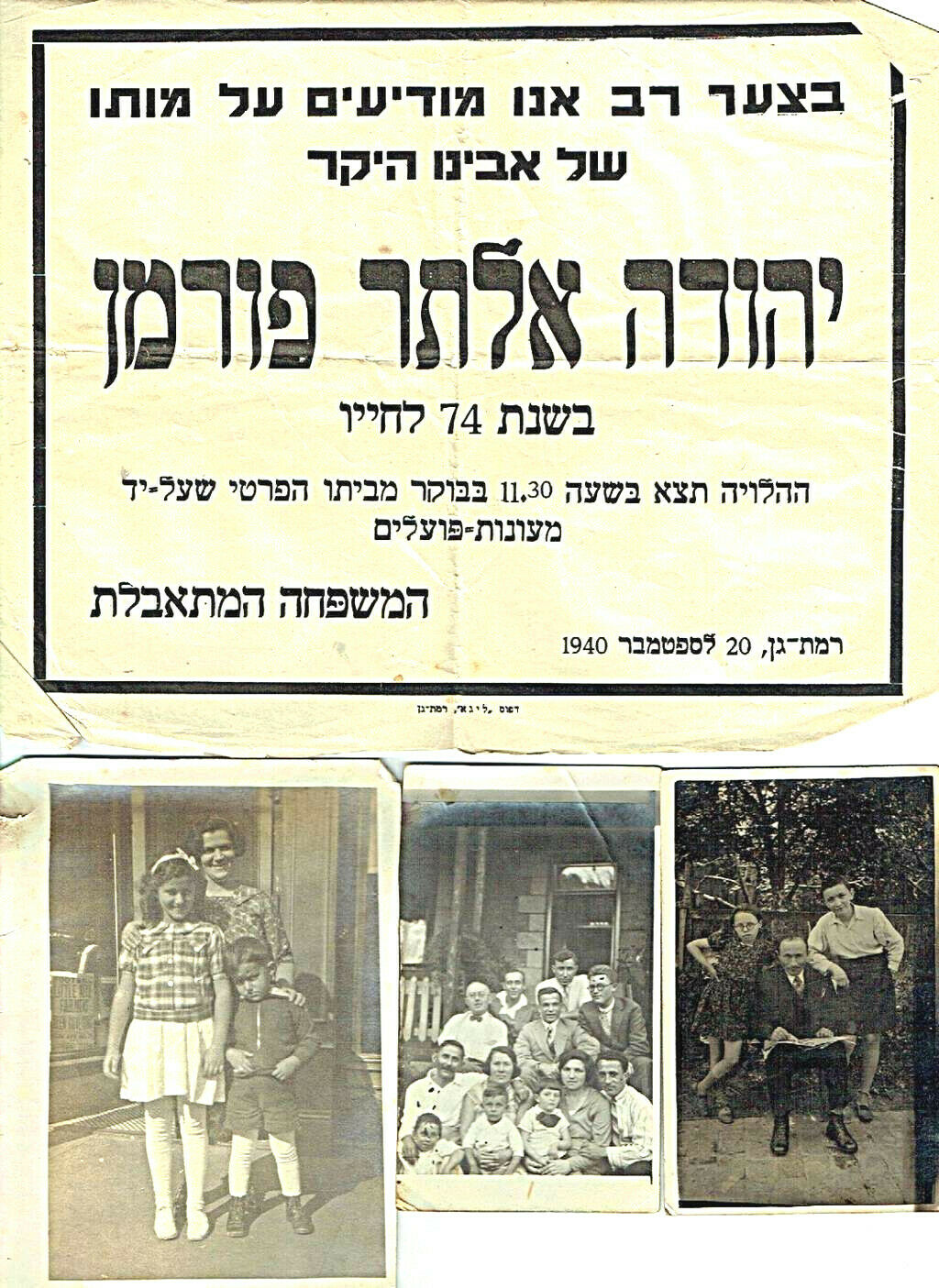

Original SIGNED LITHOGRAPH Jewish HEBREW BAKERY Israel BREAD SHOP Judaica 1950s

$ 50.16

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION: This original HAND SIGNED and NUMBERED colorful STONE LITHOGRAPH provides an amazing image of URBAN STREET SCENE very likely in TEL AVIV in the 1940's or 1950's ( Eretz Israel - Palestine era ), before or right after the birth of the INDEPENDENT ISRAEL STATE , Depicting a JEWISH KOSHER BAKERY or BREAD SHOP , BAKER SHOP with a typical interaction among the different types of BREAD and BUN buyers.

It's an ORIGINAL HAND SIGNED With pencil and NUMBERED LITHOGRAPH ( xxx /300 ) by the Israeli artist Larisa Heller . Size of the sheet is around 19" x 26" . Size of the actual image is 13.5"x14.5" - Not accurate . Very good condition.

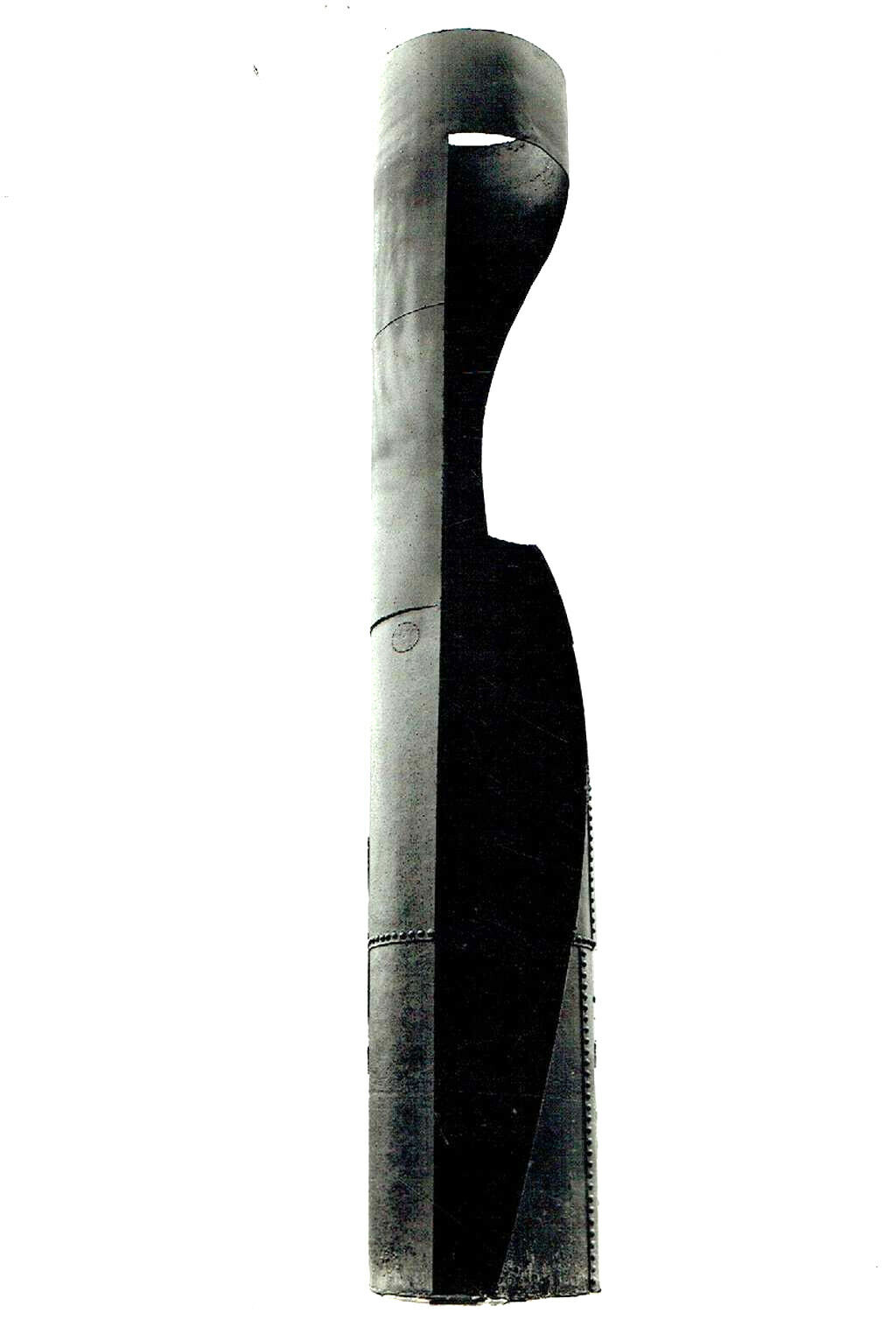

( Pls look at scan for actual AS IS images ) Will be sent rolled inside a protective rigid tube.

PAYMENTS

: Payment method accepted : Paypal

& All credit cards

.

SHIPPMENT

: SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is $ 25 .

Will be sent rolled inside a protective rigid tube.

Handling around 5-10 days after payment.

Bread is a staple food prepared from a dough of flour and water, usually by baking. Throughout recorded history it has been a prominent food in large parts of the world and is one of the oldest man-made foods, having been of significant importance since the dawn of agriculture. Bread may be leavened by processes such as reliance on naturally occurring sourdough microbes, chemicals, industrially produced yeast, or high-pressure aeration. Commercial bread commonly contains additives to improve flavor, texture, color, shelf life, nutrition, and ease of manufacturing. Bread plays essential roles in religious rituals and secular culture. Contents 1 Etymology 2 History 3 Types 4 Properties 4.1 Physical-chemical composition 4.2 Culinary uses 4.3 Nutritional significance 4.4 Crust 5 Preparation 5.1 Formulation 5.2 Flour 5.3 Liquids 5.4 Fats or shortenings 5.5 Bread improvers 5.6 Salt 6 Leavening 6.1 Chemicals 6.2 Yeast 6.3 Sourdough 6.4 Steam 6.5 Bacteria 6.6 Aeration 7 Cultural significance 8 See also 9 References 10 Further reading 11 External links Etymology The Old English word for bread was hlaf (hlaifs in Gothic: modern English loaf), which appears to be the oldest Teutonic name.[1] Old High German hleib[2] and modern German Laib derive from this Proto-Germanic word, which was borrowed into Slavic (Polish chleb, Russian khleb) and Finnic (Finnish leipä, Estonian leib) languages as well. The Middle and Modern English word bread appears in Germanic languages, such as West Frisian brea, Dutch brood, German Brot, Swedish bröd, and Norwegian and Danish brød; it may be related to brew or perhaps to break, originally meaning "broken piece", "morsel".[3] History Main article: History of bread Bread shop, Tacuinum Sanitatis from Northern Italy, beginning of the 15th century Bread is one of the oldest prepared foods. Evidence from 30,000 years ago in Europe revealed starch residue on rocks used for pounding plants.[4] It is possible that during this time, starch extract from the roots of plants, such as cattails and ferns, was spread on a flat rock, placed over a fire and cooked into a primitive form of flatbread. The world's oldest evidence of bread-making has been found in a 14,500-year-old Natufian site in Jordan's northeastern desert.[5][6] Around 10,000 BC, with the dawn of the Neolithic age and the spread of agriculture, grains became the mainstay of making bread. Yeast spores are ubiquitous, including on the surface of cereal grains, so any dough left to rest leavens naturally.[7] There were multiple sources of leavening available for early bread. Airborne yeasts could be harnessed by leaving uncooked dough exposed to air for some time before cooking. Pliny the Elder reported that the Gauls and Iberians used the foam skimmed from beer called barm to produce "a lighter kind of bread than other peoples" such as barm cake. Parts of the ancient world that drank wine instead of beer used a paste composed of grape juice and flour that was allowed to begin fermenting, or wheat bran steeped in wine, as a source for yeast. The most common source of leavening was to retain a piece of dough from the previous day to use as a form of sourdough starter, as Pliny also reported.[8][9] The Chorleywood bread process was developed in 1961; it uses the intense mechanical working of dough to dramatically reduce the fermentation period and the time taken to produce a loaf. The process, whose high-energy mixing allows for the use of grain with a lower protein content, is now widely used around the world in large factories. As a result, bread can be produced very quickly and at low costs to the manufacturer and the consumer. However, there has been some criticism of the effect on nutritional value.[10][11][12] Types Main article: List of breads Brown bread (left) and whole grain bread Dark sprouted bread Bread is the staple food of the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa, Europe, and in European-derived cultures such as those in the Americas, Australia, and Southern Africa, in contrast to parts of South and East Asia where rice or noodle is the staple. Bread is usually made from a wheat-flour dough that is cultured with yeast, allowed to rise, and finally baked in an oven. The addition of yeast to the bread explains the air pockets commonly found in bread.[13] Owing to its high levels of gluten (which give the dough sponginess and elasticity), common or bread wheat is the most common grain used for the preparation of bread, which makes the largest single contribution to the world's food supply of any food.[14] Strucia — a type of European sweet bread Bread is also made from the flour of other wheat species (including spelt, emmer, einkorn and kamut).[15] Non-wheat cereals including rye, barley, maize (corn), oats, sorghum, millet and rice have been used to make bread, but, with the exception of rye, usually in combination with wheat flour as they have less gluten.[16] Gluten-free breads are made using ground flours from a variety of ingredients such as almonds, rice, sorghum, corn, or legumes such as beans, and tubers such as cassava, but since these flours lack gluten they may not hold their shape as they rise and their crumb may be dense with little aeration. Additives such as xanthan gum, guar gum, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), corn starch, or eggs are used to compensate for the lack of gluten.[17][18][19][20] Properties Physical-chemical composition In wheat, phenolic compounds are mainly found in hulls in the form of insoluble bound ferulic acid, where it is relevant to wheat resistance to fungal diseases.[21] Rye bread contains phenolic acids and ferulic acid dehydrodimers.[22] Three natural phenolic glucosides, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, p-coumaric acid glucoside and ferulic acid glucoside, can be found in commercial breads containing flaxseed.[23] Glutenin and gliadin are functional proteins found in wheat bread that contribute to the structure of bread. Glutenin forms interconnected gluten networks within bread through interchain disulfide bonds.[24] Gliadin binds weakly to the gluten network established by glutenin via intrachain disulfide bonds.[24] Structurally, bread can be defined as an elastic-plastic foam (same as styrofoam). The glutenin protein contributes to its elastic nature, as it is able to regain its initial shape after deformation. The gliadin protein contributes to its plastic nature, because it demonstrates non-reversible structural change after a certain amount of applied force. Because air pockets within this gluten network result from carbon dioxide production during leavening, bread can be defined as a foam, or a gas-in-solid solution.[25] Acrylamide, like in other starchy foods that have been heated higher than 120 °C (248 °F), has been found in recent years to occur in bread. Acrylamide is neurotoxic, has adverse effects on male reproduction and developmental toxicity and is carcinogenic. A study has found that more than 99 percent of the acrylamide in bread is found in the crust.[26] Culinary uses Bread pudding Bread can be served at many temperatures; once baked, it can subsequently be toasted. It is most commonly eaten with the hands, either by itself or as a carrier for other foods. Bread can be dipped into liquids such as gravy, olive oil, or soup;[27] it can be topped with various sweet and savory spreads, or used to make sandwiches containing meats, cheeses, vegetables, and condiments.[28] Bread is used as an ingredient in other culinary preparations, such as the use of breadcrumbs to provide crunchy crusts or thicken sauces, sweet or savoury bread puddings, or as a binding agent in sausages and other ground meat products.[29] Nutritional significance Nutritionally, bread is categorized as a source of grains in the food pyramid and is a good source of carbohydrates and nutrients such as magnesium, iron, selenium, B vitamins, and dietary fiber.[30] Crust Crust of a cut bread made of whole-grain rye with crust crack (half right at the top) Bread crust is formed from surface dough during the cooking process. It is hardened and browned through the Maillard reaction using the sugars and amino acids and the intense heat at the bread surface. The crust of most breads is harder, and more complexly and intensely flavored, than the rest. Old wives' tales suggest that eating the bread crust makes a person's hair curlier.[31] Additionally, the crust is rumored to be healthier than the remainder of the bread. Some studies have shown that this is true as the crust has more dietary fiber and antioxidants such as pronyl-lysine,[32][33] which is being researched for its potential colorectal cancer inhibitory properties.[34][35] Preparation Steps in bread making, here for an unleavened Chilean tortilla Doughs are usually baked, but in some cuisines breads are steamed (e.g., mantou), fried (e.g., puri), or baked on an unoiled frying pan (e.g., tortillas). It may be leavened or unleavened (e.g. matzo). Salt, fat and leavening agents such as yeast and baking soda are common ingredients, though bread may contain other ingredients, such as milk, egg, sugar, spice, fruit (such as raisins), vegetables (such as onion), nuts (such as walnut) or seeds (such as poppy).[36] Methods of processing dough into bread include the straight dough process, the sourdough process, the Chorleywood bread process and the sponge and dough process. Baking bread in East Timor Formulation Professional bread recipes are stated using the baker's percentage notation. The amount of flour is denoted to be 100%, and the other ingredients are expressed as a percentage of that amount by weight. Measurement by weight is more accurate and consistent than measurement by volume, particularly for dry ingredients. The proportion of water to flour is the most important measurement in a bread recipe, as it affects texture and crumb the most. Hard wheat flours absorb about 62% water, while softer wheat flours absorb about 56%.[37] Common table breads made from these doughs result in a finely textured, light bread. Most artisan bread formulas contain anywhere from 60 to 75% water. In yeast breads, the higher water percentages result in more CO2 bubbles and a coarser bread crumb. 500 grams (1 pound) of flour yields a standard loaf of bread or two baguettes. Calcium propionate is commonly added by commercial bakeries to retard the growth of molds.[38] Flour Main article: Flour Flour is grain ground to a powdery consistency. Flour provides the primary structure, starch and protein to the final baked bread. The protein content of the flour is the best indicator of the quality of the bread dough and the finished bread. While bread can be made from all-purpose wheat flour, a specialty bread flour, containing more protein (12–14%), is recommended for high-quality bread. If one uses a flour with a lower protein content (9–11%) to produce bread, a shorter mixing time is required to develop gluten strength properly. An extended mixing time leads to oxidization of the dough, which gives the finished product a whiter crumb, instead of the cream color preferred by most artisan bakers.[39] Wheat flour, in addition to its starch, contains three water-soluble protein groups (albumin, globulin, and proteoses) and two water-insoluble protein groups (glutenin and gliadin). When flour is mixed with water, the water-soluble proteins dissolve, leaving the glutenin and gliadin to form the structure of the resulting bread. When relatively dry dough is worked by kneading, or wet dough is allowed to rise for a long time (see no-knead bread), the glutenin forms strands of long, thin, chainlike molecules, while the shorter gliadin forms bridges between the strands of glutenin. The resulting networks of strands produced by these two proteins are known as gluten. Gluten development improves if the dough is allowed to autolyse.[40] Liquids Water, or some other liquid, is used to form the flour into a paste or dough. The weight of liquid required varies between recipes, but a ratio of 3 parts liquid to 5 parts flour is common for yeast breads.[41] Recipes that use steam as the primary leavening method may have a liquid content in excess of 1 part liquid to 1 part flour. Instead of water, recipes may use liquids such as milk or other dairy products (including buttermilk or yoghurt), fruit juice, or eggs. These contribute additional sweeteners, fats, or leavening components, as well as water.[42] Fats or shortenings Fats, such as butter, vegetable oils, lard, or that contained in eggs, affect the development of gluten in breads by coating and lubricating the individual strands of protein. They also help to hold the structure together. If too much fat is included in a bread dough, the lubrication effect causes the protein structures to divide. A fat content of approximately 3% by weight is the concentration that produces the greatest leavening action.[43] In addition to their effects on leavening, fats also serve to tenderize breads and preserve freshness. Bread improvers Main article: Bread improver Bread improvers and dough conditioners are often used in producing commercial breads to reduce the time needed for rising and to improve texture and volume. The substances used may be oxidising agents to strengthen the dough or reducing agents to develop gluten and reduce mixing time, emulsifiers to strengthen the dough or to provide other properties such as making slicing easier, or enzymes to increase gas production.[44] Salt Salt (sodium chloride) is very often added to enhance flavor and restrict yeast activity. It also affects the crumb and the overall texture by stabilizing and strengthening[45] the gluten. Some artisan bakers forego early addition of salt to the dough, whether wholemeal or refined, and wait until after a 20-minute rest to allow the dough to autolyse.[46] Mixtures of salts are sometimes employed, such as employing potassium chloride to reduce the sodium level, and monosodium glutamate to give flavor (umami). Leavening A dough trough, located in Aberdour Castle, once used for leavening bread. Leavening is the process of adding gas to a dough before or during baking to produce a lighter, more easily chewed bread. Most bread eaten in the West is leavened.[47] Chemicals A simple technique for leavening bread is the use of gas-producing chemicals. There are two common methods. The first is to use baking powder or a self-raising flour that includes baking powder. The second is to include an acidic ingredient such as buttermilk and add baking soda; the reaction of the acid with the soda produces gas.[47] Chemically leavened breads are called quick breads and soda breads. This method is commonly used to make muffins, pancakes, American-style biscuits, and quick breads such as banana bread. Yeast Main article: Baker's yeast Compressed fresh yeast Many breads are leavened by yeast. The yeast most commonly used for leavening bread is Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the same species used for brewing alcoholic beverages. This yeast ferments some of the carbohydrates in the flour, including any sugar, producing carbon dioxide. Commercial bakers often leaven their dough with commercially produced baker's yeast. Baker's yeast has the advantage of producing uniform, quick, and reliable results, because it is obtained from a pure culture.[47] Many artisan bakers produce their own yeast with a growth culture. If kept in the right conditions, it provides leavening for many years.[48] The baker's yeast and sourdough methods follow the same pattern. Water is mixed with flour, salt and the leavening agent. Other additions (spices, herbs, fats, seeds, fruit, etc.) are not needed to bake bread, but are often used. The mixed dough is then allowed to rise one or more times (a longer rising time results in more flavor, so bakers often "punch down" the dough and let it rise again), then loaves are formed, and (after an optional final rising time) the bread is baked in an oven.[47] Many breads are made from a "straight dough", which means that all of the ingredients are combined in one step, and the dough is baked after the rising time;[47] others are made from a "pre-ferment" in which the leavening agent is combined with some of the flour and water a day or so ahead of baking and allowed to ferment overnight. On the day of baking, the rest of the ingredients are added, and the process continues as with straight dough. This produces a more flavorful bread with better texture. Many bakers see the starter method as a compromise between the reliable results of baker's yeast and the flavor and complexity of a longer fermentation. It also allows the baker to use only a minimal amount of baker's yeast, which was scarce and expensive when it first became available. Most yeasted pre-ferments fall into one of three categories: "poolish" or "pouliche", a loose-textured mixture composed of roughly equal amounts of flour and water (by weight); "biga", a stiff mixture with a higher proportion of flour; and "pâte fermentée", which is simply a portion of dough reserved from a previous batch.[49][50] Before first rising After first rising After proofing, ready to bake Sourdough loaves Sourdough Main article: Sourdough Sourdough is a type of bread produced by a long fermentation of dough using naturally occurring yeasts and lactobacilli. It usually has a mildly sour taste because of the lactic acid produced during anaerobic fermentation by the lactobacilli.[51][52] Sourdough breads are made with a sourdough starter. The starter cultivates yeast and lactobacilli in a mixture of flour and water, making use of the microorganisms already present on flour; it does not need any added yeast. A starter may be maintained indefinitely by regular additions of flour and water. Some bakers have starters many generations old, which are said to have a special taste or texture.[51] At one time, all yeast-leavened breads were sourdoughs. Recently there has been a revival of sourdough bread in artisan bakeries.[53] Traditionally, peasant families throughout Europe baked on a fixed schedule, perhaps once a week. The starter was saved from the previous week's dough. The starter was mixed with the new ingredients, the dough was left to rise, and then a piece of it was saved (to be the starter for next week's bread).[47] Steam The rapid expansion of steam produced during baking leavens the bread, which is as simple as it is unpredictable. Steam-leavening is unpredictable since the steam is not produced until the bread is baked. Steam leavening happens regardless of the raising agents (baking soda, yeast, baking powder, sour dough, beaten egg white) included in the mix. The leavening agent either contains air bubbles or generates carbon dioxide. The heat vaporises the water from the inner surface of the bubbles within the dough. The steam expands and makes the bread rise. This is the main factor in the rising of bread once it has been put in the oven.[54] CO2 generation, on its own, is too small to account for the rise. Heat kills bacteria or yeast at an early stage, so the CO2 generation is stopped. Bacteria Salt-rising bread employs a form of bacterial leavening that does not require yeast. Although the leavening action is inconsistent, and requires close attention to the incubating conditions, this bread is making a comeback for its cheese-like flavor and fine texture.[55] Aeration Aerated bread was leavened by carbon dioxide being forced into dough under pressure. From the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, bread made this way was somewhat popular in the United Kingdom, made by the Aerated Bread Company and sold in its high-street tearooms. The company was founded in 1862, and ceased independent operations in 1955.[56] The Pressure-Vacuum mixer was later developed by the Flour Milling and Baking Research Association for the Chorleywood bread process. It manipulates the gas bubble size and optionally the composition of gases in the dough via the gas applied to the headspace.[57] Cultural significance A Ukrainian woman in national dress welcoming with bread and salt Main article: Bread in culture Bread has a significance beyond mere nutrition in many cultures because of its history and contemporary importance. Bread is also significant in Christianity as one of the elements (alongside wine) of the Eucharist,[58] and in other religions including Paganism.[59] In many cultures, bread is a metaphor for basic necessities and living conditions in general. For example, a "bread-winner" is a household's main economic contributor and has little to do with actual bread-provision. This is also seen in the phrase "putting bread on the table". The Roman poet Juvenal satirized superficial politicians and the public as caring only for "panem et circenses" (bread and circuses).[60] In Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks promised "peace, land, and bread."[61][62] The term "breadbasket" denotes an agriculturally productive region. In Slavic cultures bread and salt is offered as a welcome to guests.[63] In India, life's basic necessities are often referred to as "roti, kapra aur makan" (bread, cloth, and house).[64] Words for bread, including "dough" and "bread" itself, are used in English-speaking countries as synonyms for money.[1] A remarkable or revolutionary innovation may be called the best thing since "sliced bread".[65] The expression "to break bread with someone" means "to share a meal with someone".[66] The English word "lord" comes from the Anglo-Saxon hlāfweard, meaning "bread keeper."[67] Bread is sometimes referred to as "the staff of life", although this term can refer to other staple foods in different cultures: the Oxford English Dictionary defines it as "bread (or similar staple food)".[68][69] This is sometimes thought to be a biblical reference, but the nearest wording is in Leviticus 26 "when I have broken the staff of your bread".[70] The term has been adopted in the names of bakery firms.[71]*** A bakery (also baker's shop or bake shop) is an establishment that produces and sells flour-based food baked in an oven such as bread, cookies, cakes, pastries, and pies.[1] Some retail bakeries are also cafés, serving coffee and tea to customers who wish to consume the baked goods on the premises. Contents 1 History 2 Products 3 Specialities 4 Commercialization 5 See also 6 References 7 External links History[edit] Advertisement for a bakery in Germany since 1442 Bakery window with breads and cakes on display, 1936 Village bakehouse in Geyerbad near Oberdigisheim (Meßstetten) Baked goods have been around for thousands of years. The art of baking was developed early during the Roman Empire. It was a highly famous art as Roman citizens loved baked goods and demanded for them frequently for important occasions such as feasts and weddings etc. Due to the fame and desire that the art of baking received, around 300 BC, baking was introduced as an occupation and respectable profession for Romans. The bakers began to prepare bread at home in an oven, using mills to grind grain into the flour for their breads. The oncoming demand for baked goods vigorously continued and the first bakers' guild was established in 168 BC in Rome. This drastic appeal for baked goods promoted baking all throughout Europe and expanded into the eastern parts of Asia. Bakers started baking breads and goods at home and selling them out on the streets. This trend became common and soon, baked products were getting sold in streets of Rome, Germany, London and many more. This resulted in a system of delivering the goods to households, as the demand for baked breads and goods significantly increased. This provoked the bakers to establish a place where people could purchase baked goods for themselves. Therefore, in Paris, the first open-air bakery of baked goods was developed and since then, bakeries became a common place to purchase delicious goods and get together around the world. By the colonial era, bakeries were commonly viewed as places to gather and socialize.[2] On July 7, 1928, a bakery in Chillicothe, Missouri introduced pre-cut bread using the automatic bread-slicing machine, invented by Otto Frederick Rohwedder. While the bread initially failed to sell, due to its "sloppy" aesthetic, and the fact it went stale faster,[3] it later became popular. In World War II bread slicing machines were effectively banned, as the metal in them was required for wartime use. When they were requisitioned, creating 100 tonnes of metal alloy, the decision proved very unpopular with housewives.[4] World War II directly affected bread industries in the UK. Baking schools closed during this time so when the war did eventually end there was an absence of skilled bakers. This resulted in new methods being developed to satisfy the world’s desire for bread. Methods like: adding chemicals to dough, premixes and specialised machinery. These old methods of baking were almost completely eradicated when these new methods were introduced and became industrialised. The old methods were seen as unnecessary and financially unsound, during this period there were not many traditional bakeries left. Products[edit] Bread Bread roll Flatbreads Bagels Doughnuts Muffins Pizzas Buns Pastries Pies Crumpets Tarts Brownies Cakes Croissants Cupcakes Cookies Scones Barmbrack Soda bread Biscuit (bread) Crackers Biscuits Pretzels Biscotti Cornbread Pandesal Pumpkin bread Pita Sourdough Potato bread Specialities[edit] Some bakeries provide services for special occasions (such as weddings, birthday parties, anniversaries, or even business events) or for people who have allergies or sensitivities to certain foods (such as nuts, peanuts, dairy or gluten). Bakeries can provide a wide range of cakes designs such as sheet cakes, layer cakes, tiered cakes, and wedding cakes. Other bakeries may specialize in traditional or hand made types of bread made with locally milled flour, without flour bleaching agents or flour treatment agents, baking what is sometimes referred to as artisan bread.[1] Commercialization[edit] Grocery stores and supermarkets, in many countries, sell prepackaged or pre-sliced bread, cakes, and other pastries. They can also offer in-store baking and basic cake decoration.[2] Nonetheless, many people still prefer to get their baked goods from a small artisanal bakery, either out of tradition, the availability of a greater variety of baked goods, or due to the higher quality products characteristic of the trade of baking.[1] See also[edit] Food portal Baker, a person who produces baked goods Baking Cake decorating Cake shop Coffeehouse Konditorei, a German shop that makes, sells and serves cakes, pastries, coffee and tea, in mornings and afternoons List of baked goods List of bakeries List of bakery cafés List of doughnut shops Pâtisserie, a French or Belgian establishment that specializes in pastries Sliced bread, before bread slicing machines were invented people would buy whole loaves of bread and cut them at home Tea house . EBAY4716