-40%

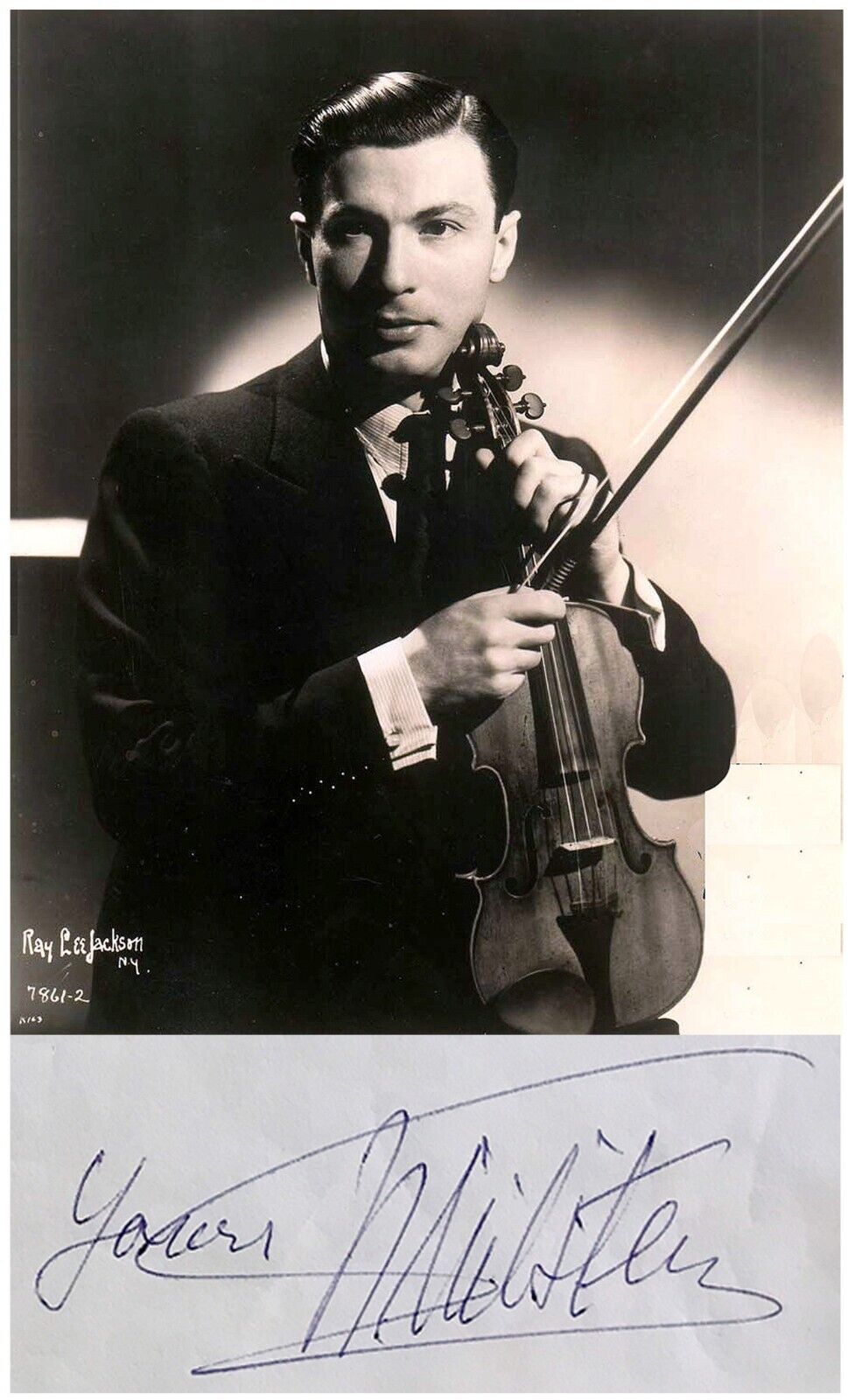

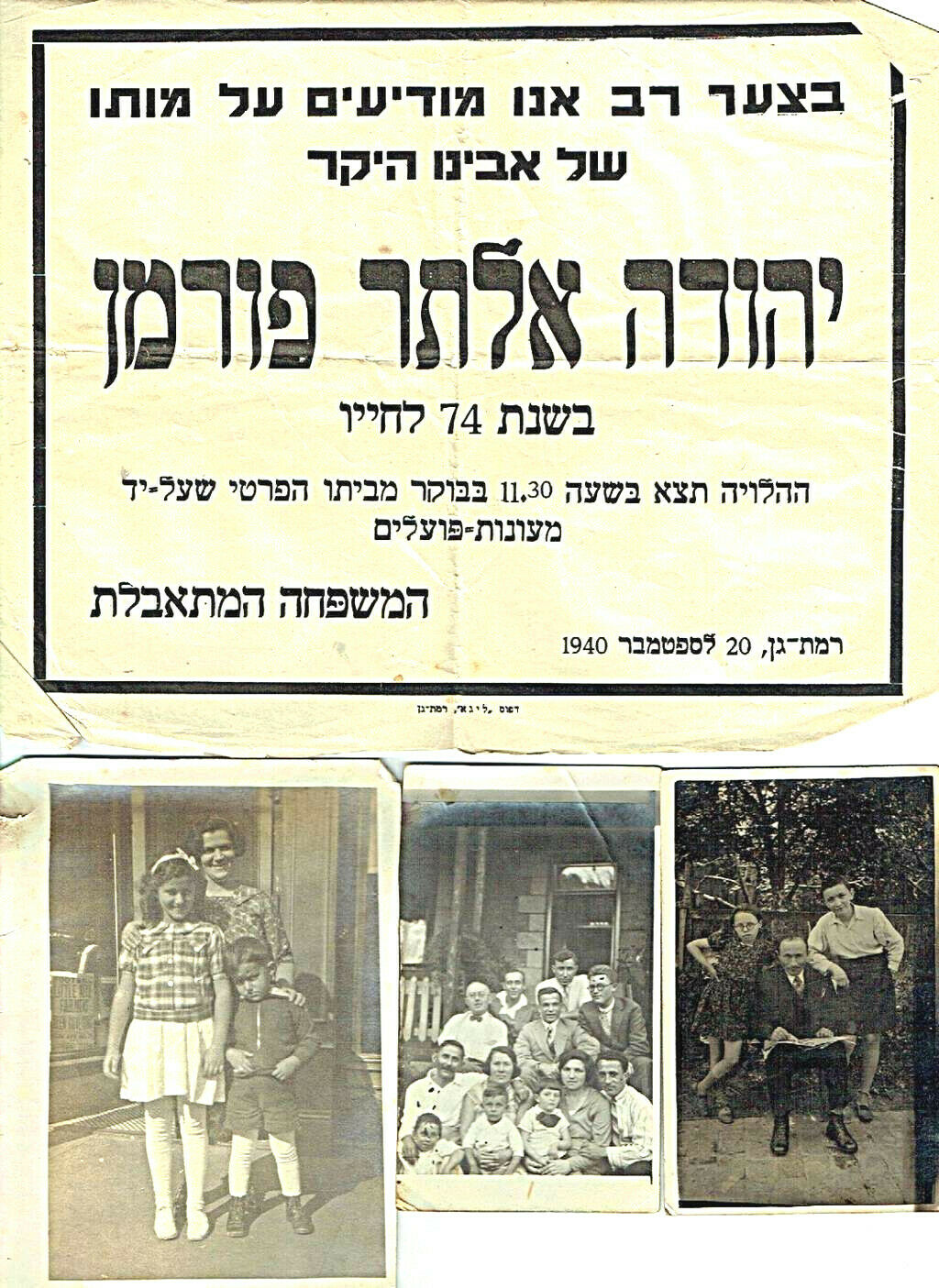

Violinist NATHAN MILSTEIN Rare HAND SIGNED AUTOGRAPH + PHOTO + MAT Jewish VIOLIN

$ 198

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

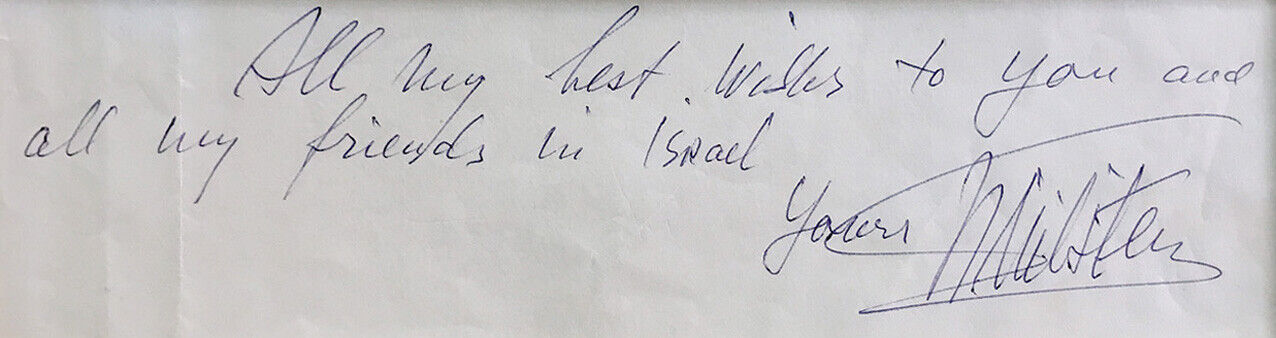

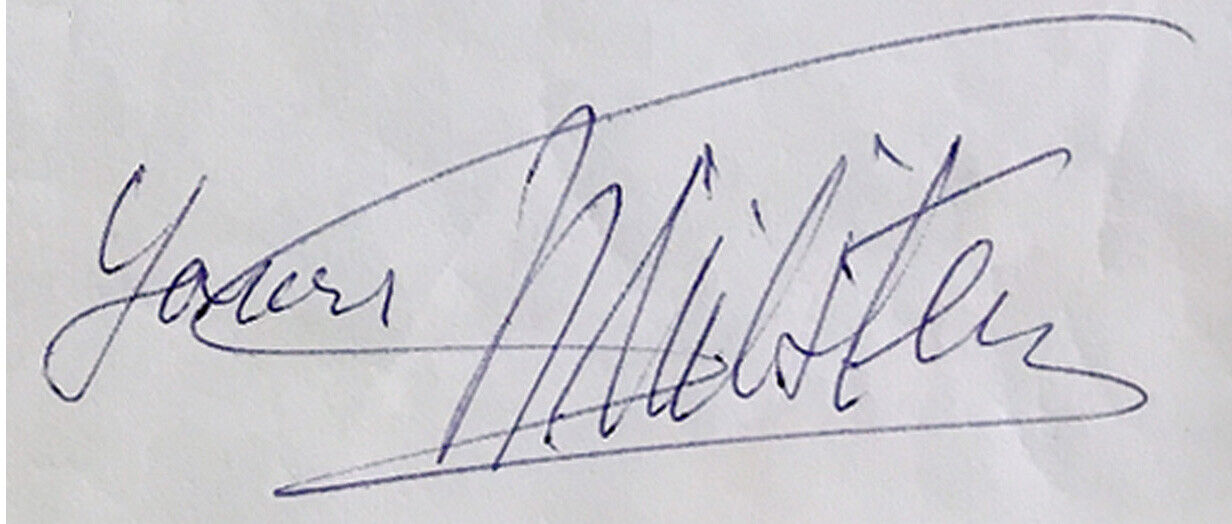

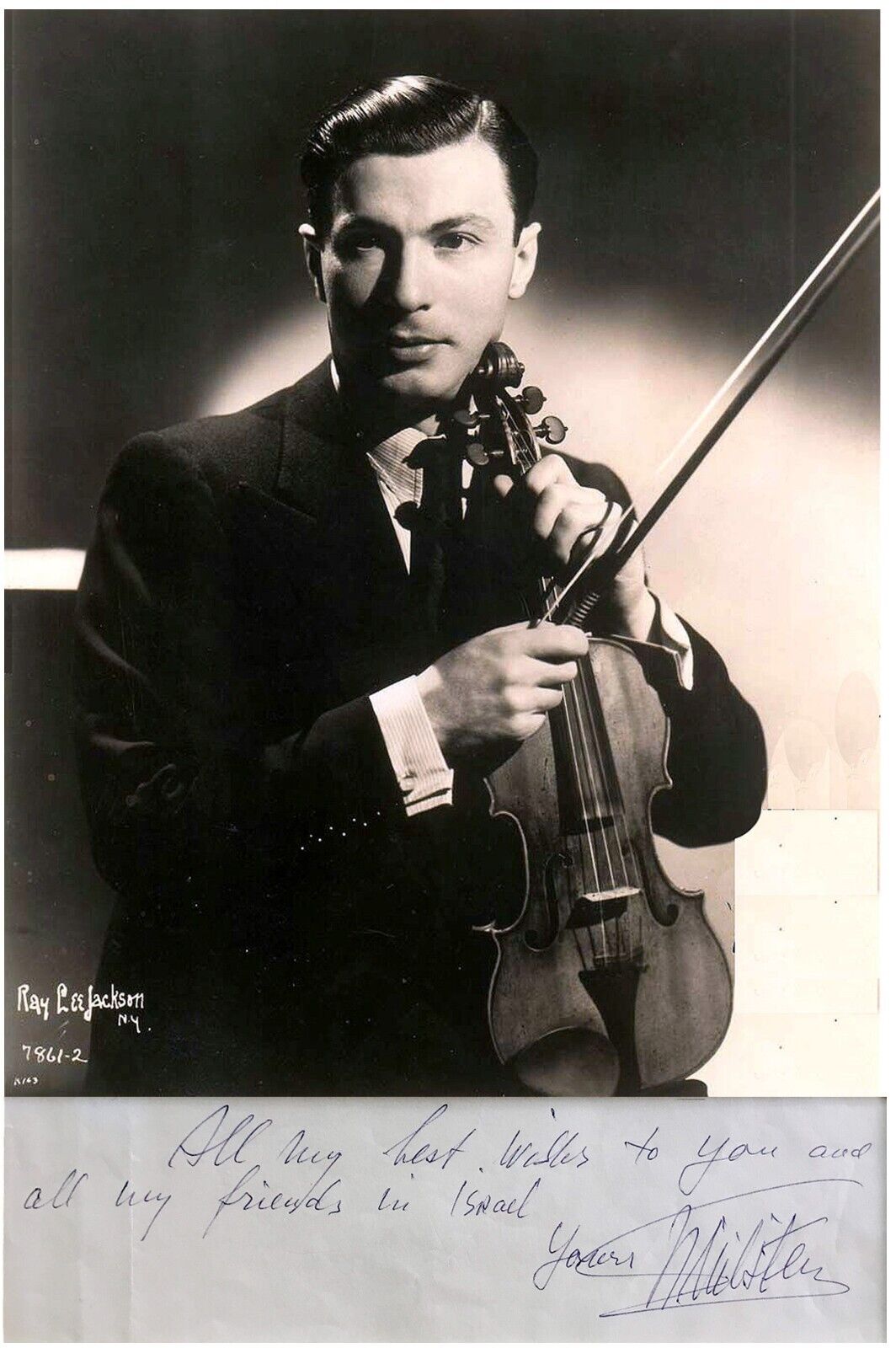

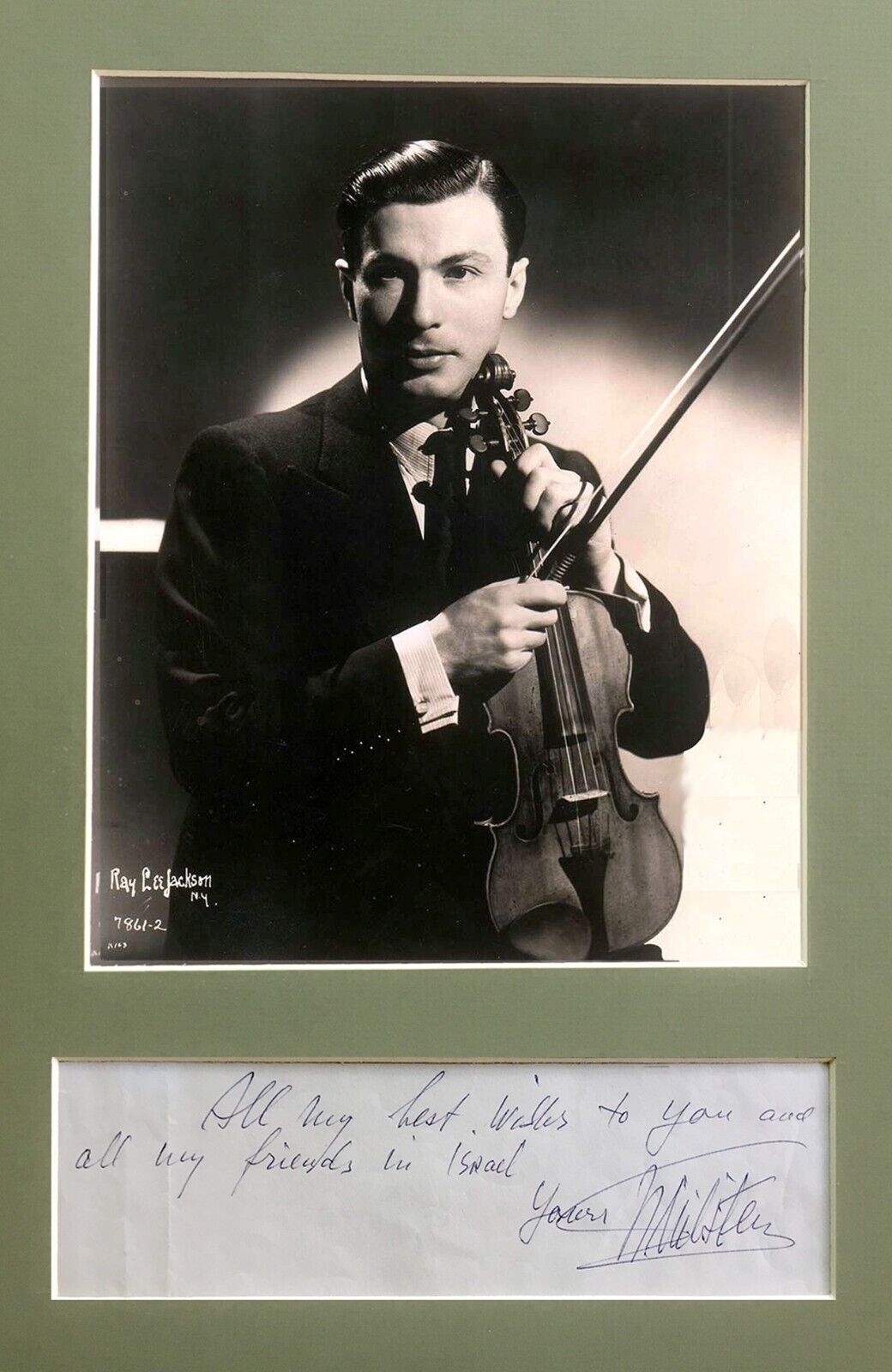

Up for auction is an original BEAUTIFUL , BOLDLY HAND SIGNED AUTOGRAPHED long SENTIMENT

( Autograph -Signature - Autogramme ) With a blue pen of the beloved legendary Jewish violinist of Russian descent, Who is w

idely considered one of the finest violinists of the 20th century ,

The child prodigy NATHAN MILSTEIN . The sentiment is to a friend or coleague in Israel.

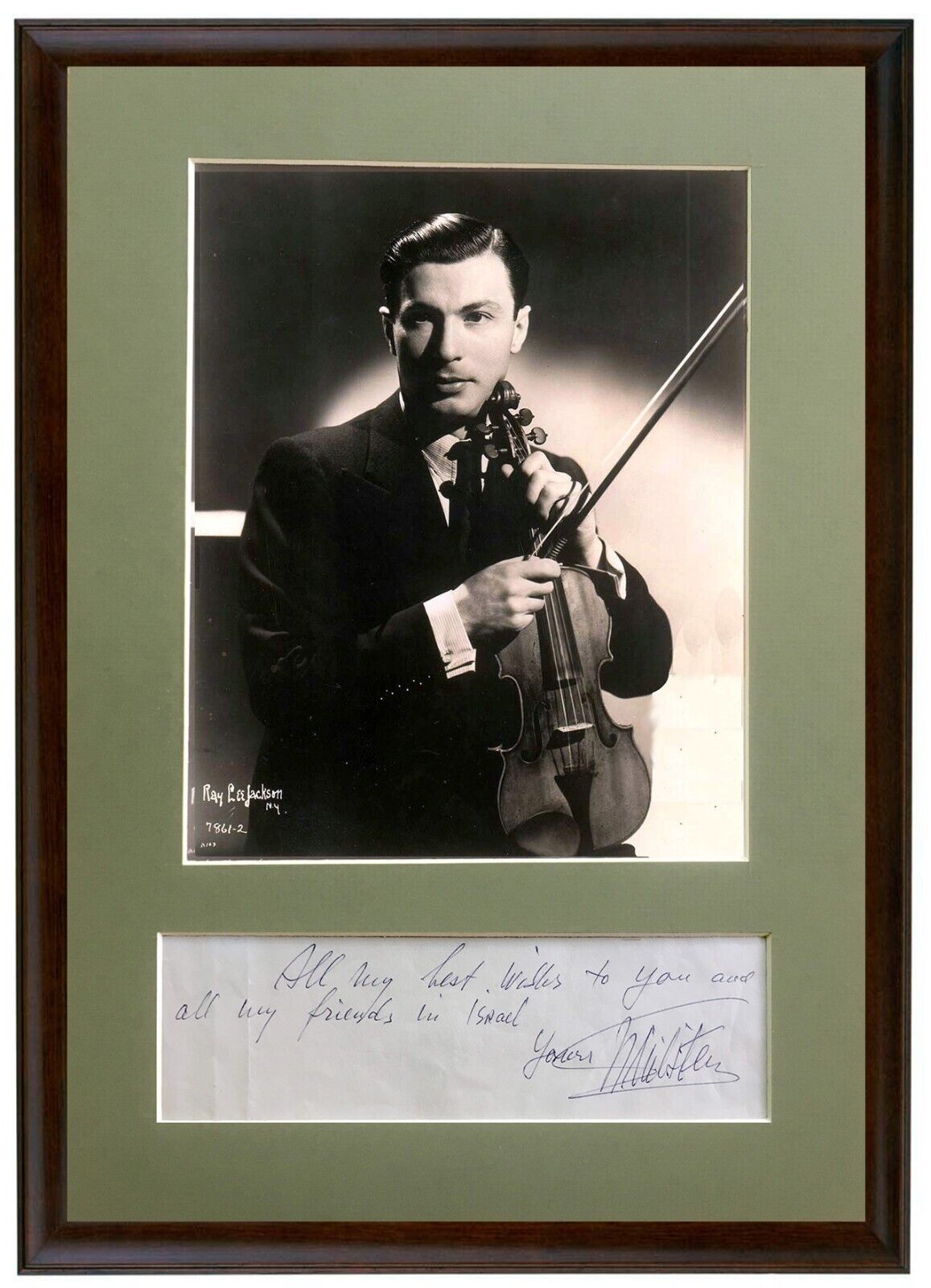

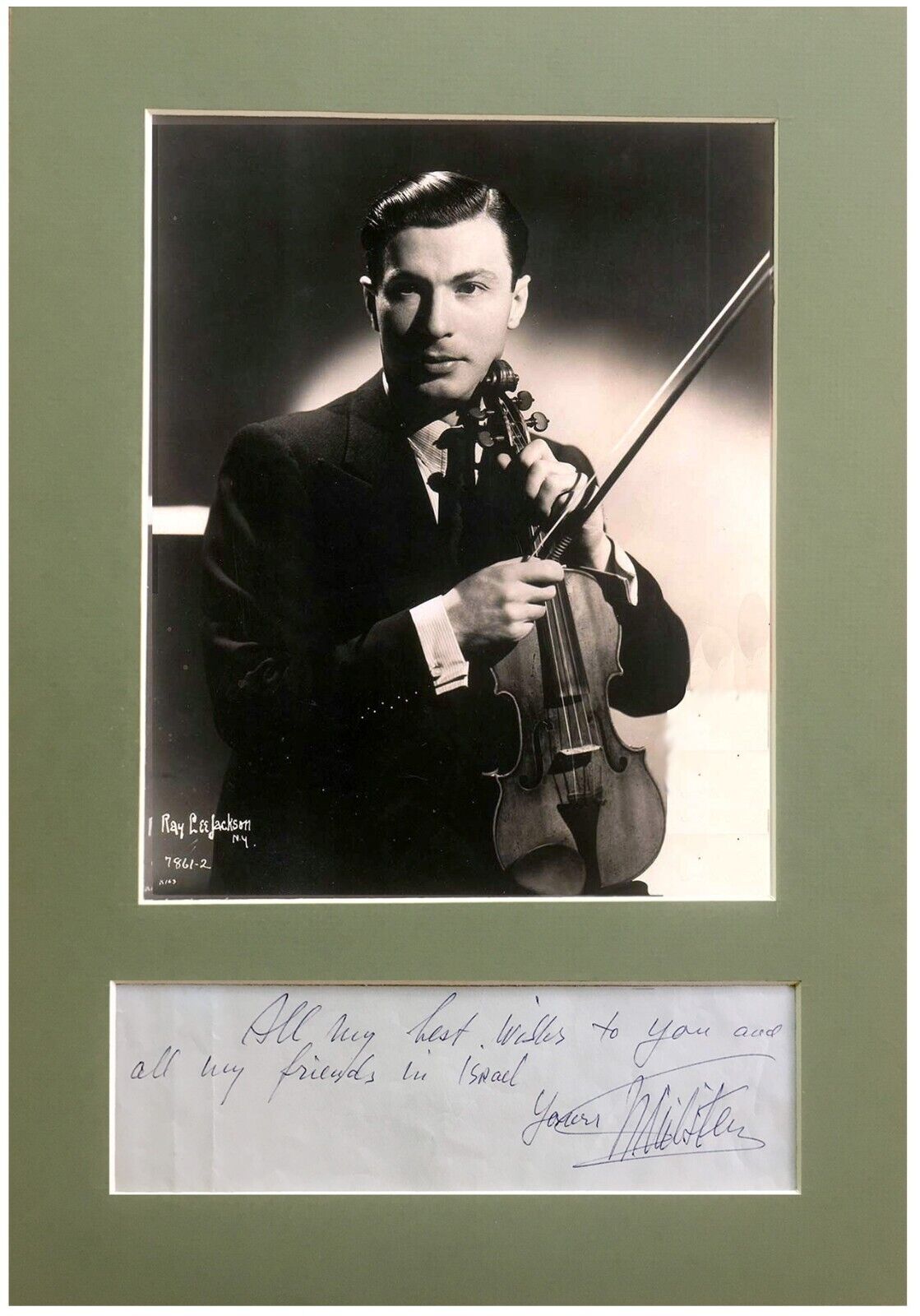

The original AUTOGRAPH SENTIMENT is beautifuly and professionaly matted beneath an IMPRESSIVE reproduction ARTISTIC PHOTO of quite young and heart breaking handsome MILSTEIN holding his violin. The AUTOGRAPH and the reproduction PHOTO are nicely matted together , Suitable for immediate framing or display . ( An image of a suggested framing is presented - The frame is not a part of this sale

-

An excellent framing - Buyer's choice - is possible for extra $ 80 ).

The size of the decorative mat is around

16 x 11 " . The size of the reproduction photo is around 10 x 8 " . The size of the HAND SIGNED autograph ( Autogramme - Signature ) sentiment is around

8.5 x 3 " . Excellent condition of the

HAND SIGNED autograph ( Autogramme - Signature ) sentiment

, The original reproduction photo and the decorative mat ( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS

images )

Authenticity guaranteed. Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging .

AUTHENTICITY

: The AUTOGRAPH

is fully guaranteed

ORIGINAL HAND SIGNED by MILSTEIN, It holds a life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

:

Payment method accepted : Paypal & All credit cards.

SHIPPMENT

:

SHIPP worldwide via registered airmail is . Will be sent inside a protective packaging.

Handling around 5 days after payment.

Nathan Mironovich Milstein (January 13, 1904 [O.S. December 31, 1903] – December 21, 1992) was a Jewish[1] Russian-born American virtuoso violinist. Widely considered one of the finest violinists of the 20th century, Milstein was known for his interpretations of Bach's solo violin works and for works from the Romantic period. He was also known for his long career: he performed at a high level into his mid-80s, retiring only after suffering a broken hand. Contents 1 Biography 2 See also 3 Notes 4 References 5 External links Biography[edit] Milstein was born in Odesa, Russian Empire (today Ukraine), the fourth child of seven, to a middle-class Jewish family with no musical background. It was a concert by the 11-year-old Jascha Heifetz that inspired his parents to make a violinist out of Milstein. As a child of seven, he started violin studies (as suggested by his parents, to keep him out of mischief) with the eminent violin pedagogue Pyotr Stolyarsky, also the teacher of renowned violinist David Oistrakh. When Milstein was 11, Leopold Auer invited him to become one of his students at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Milstein reminisced: Every little boy who had the dream of playing better than the other boy wanted to go to Auer. He was a very gifted man and a good teacher. I used to go to the Conservatory twice a week for classes. I played every lesson with forty or fifty people sitting and listening. Two pianos were in the classroom and a pianist accompanied us. When Auer was sick, he would ask me to come to his home.[2] Milstein may in fact have been the last of the great Russian violinists to have had personal contact with Auer. Auer did not name Milstein in his memoirs but mentions "two boys from Odessa ... both of whom disappeared after I left St. Petersburg in June 1917."[3] Neither is Milstein's name in the registry of the St Petersburg Conservatory. Milstein also studied with Eugène Ysaÿe in Belgium. He told film-maker Christopher Nupen, director of Nathan Milstein – In Portrait, that he learned almost nothing from Ysaÿe but enjoyed his company enormously. In a 1977 interview printed in High Fidelity, he said, "I went to Ysaÿe in 1926 but he never paid any attention to me. I think it might have been better this way. I had to think for myself."[4] Milstein met Vladimir Horowitz and his pianist sister Regina in 1921 when he played a recital in Kyiv. They invited him for tea at their parents' home. Milstein later said, "I came for tea and stayed three years."[5] Milstein and Horowitz performed together, as "children of the revolution", throughout the Soviet Union and struck up a lifelong friendship. In 1925, they went on a concert tour of Western Europe together. In 1929, Milstein made his American debut with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra. He eventually settled in New York and became an American citizen. He toured repeatedly throughout Europe, maintaining residences in London and Paris. A transcriber and composer, Milstein arranged many works for violin and wrote his own cadenzas for many concertos. He was obsessed with articulating each note perfectly and would often spend long periods of time working out fingerings which would make passages sound more articulated. One of his best-known compositions is Paganiniana, a set of variations on various themes from the works of Niccolò Paganini. After playing many different violins in his earlier days, Milstein finally acquired the 1716 "Goldman" Stradivarius in 1945 which he used for the rest of his life. He renamed this Stradivarius the "Maria Teresa" in honor of his daughter Maria (presently wife of Marchese GiovanAngelo Theodoli-Braschi, Duke of Nemi and Grandee of Spain, descendant from Pope Pius VI) and his wife Therese. He also performed on the 1710 ex-"Dancla" Stradivarius for a short period. In 1948, Milstein's recording of Felix Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E minor, with Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic, had the distinction of being the first catalogue item in Columbia's newly introduced long-playing twelve-inch 33 rpm vinyl records, Columbia ML 4001. External audio You may hear Nathan Milstein performing Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto in D major Opus 35 with Frederick Stock conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1940 here on archive.org Milstein was awarded the Légion d'honneur by France in 1968, and received a Grammy Award for his recording of Bach's Sonatas and Partitas in 1975. He was also awarded Kennedy Center honors by US President Ronald Reagan. A recital he gave in Stockholm in June 1986, one of his last performances, was recorded in its entirety[6] and shows the remarkable condition of his technique at age 82. A fall shortly afterward in which he severely broke his left hand ended his career. During the late 1980s, Milstein published his memoirs, From Russia to the West, in which he discussed his life of constant performance and socializing. Milstein discusses the personalities of important composers such as Alexander Glazunov, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninoff and Igor Stravinsky and conductors such as Arturo Toscanini and Leopold Stokowski, all of whom he knew personally. He also discusses his best friends, pianist Vladimir Horowitz, cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and ballet director George Balanchine, as well as other violinists such as Fritz Kreisler and David Oistrakh. Milstein was married twice, remaining married to his second wife, Therese, until his death. He died of a heart attack in London on December 21, 1992, 23 days before his 89th birthday.[7] Therese died in 1999 aged 83. ***** Essential Historical Recordings: Nathan Milstein was Born to Play the Fiddle OCTOBER 2, 2020 Hey, fellow string player! Did you know 99.9% of visitors to this site will scroll past this message without making a contribution? Many plan to pledge later, but then forget. So we're asking you to give (or whatever you can afford) right now. By Sasha Margolis If ever a violinist was born to play the fiddle, it was Nathan Milstein. One of a seemingly endless line of spectacular Russian-Jewish violin players, Milstein came into the world three years after Jascha Heifetz, and four years before David Oistrakh. His musical offerings were distinct from both Heifetz’s high-voltage perfection and Oistrakh’s expressive breadth. What Milstein brought to the music he performed was total clarity, when it came to both interpretive intent and violinistic articulation, along with a penetrating intellect that could reduce pieces to their simplest state—and one of the most natural playing mechanisms ever seen. Milstein was born in 1904 in Odessa, and studied there with Pyotr Stolyarsky, also Oistrakh’s teacher. At eleven, he journeyed to St. Petersburg, where he studied with Leopold Auer, also Heifetz’s teacher. Once Auer left for America as a result of the Revolution, Milstein was on his own. For a few years, he struggled in poverty. In 1921, he struck up a friendship with pianist Vladimir Horowitz. Soon, the two young musicians were promoted by Soviet cultural commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky as “Children of the Revolution,” and sent abroad to show off the new nation’s artistic accomplishments. Milstein never looked back. He toured Europe and South America, and in 1929 made a debut in Philadelphia. There, a critic captured his playing perfectly: “…above and beyond his prodigious technical equipment is a brilliant mind molding the music into a coherent and symmetrical whole.” For the next fifty years, Milstein enjoyed an elite solo career. In 1948, his Mendelssohn Concerto performance became the first-ever long-playing record. In 1975, he won a Grammy for his solo Bach. He became an American citizen in 1943, but after WWII was based in London and Paris. He died in London in 1992. Advertisement Milstein spent many of his waking hours with his instrument. His friend Gregor Piatigorsky, with whom he and Horowitz played in a piano trio, wrote: “…he did not give an impression of practicing at all. He just played on the fiddle and with the fiddle. I only rarely found him without the violin in his hands.” Perhaps as a result, Milstein’s technique was incredibly relaxed and reliable—he was able to play at a high level into his eighties. He didn’t use a shoulder pad, believing that one ought to support the violin with the left hand. He also believed in bowing primarily from the shoulder, with minimal wrist motion. Musically, Milstein was a classicist, emphasizing symmetries of phrasing and simplicity of structure. Comparing his interpretations with those of other violinists underlines how Milstein prioritized long phrase units over small changes of mood or color. He never played a note without musical direction, and could drive toward climaxes with incredible intensity. His vibrato, never a mark of idiosyncratic individuality in the manner of a Heifetz or Kreisler, could nonetheless raise the music to a feverish temperature. His intonation was on par with Heifetz’s, his fast passages stunningly clear, and his spiccato and ricochet almost startlingly articulate. His on-the-string bowing tended toward a certain fullness of articulation. He did not use an up-bow staccato, even where called for in the music. Advertisement Brahms concerto with Fistoulari and the Philharmonia As for Milstein’s recordings: it may be said that in certain repertoire areas where the music can benefit from overt emoting and active styling, Milstein’s renditions might not satisfy the way a Heifetz’s or Menuhin’s will. Indeed, Milstein avoided certain pieces, such as Zigeunerweisen and the Sibelius Concerto, which he considered to be Heifetz’s property. In some other works, however, Milstein is close to peerless. Curiously, he criticized the Brahms Concerto as “a failed imitation of the Beethoven Concerto.” Despite this, his Brahms, with Fistoulari and the Philharmonia, is perhaps his finest concerto interpretation, relentlessly energetic and unencumbered by any musical clutter, so that the work is able to stand tall in all its mountainous glory. Much the same can be said of his Mendelssohn and Beethoven concerti, both with Steinberg and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Of special note is the Goldmark Concerto, in which Milstein had no rival (recorded with Blech and the Philharmonia). In the Brahms Double with Piatigorsky, the two soloists, accompanied by Reiner and Philadelphia (known in the summer and billed here as the Robin Hood Dell Orchestra), blend perfectly in a towering display of great string playing. Goldmark concerto with Blech and the Philharmonia In his day, Milstein was considered, along with Henryk Szeryng, one of the great Bach players. Contemporary listeners exposed to historical practice may find Milstein’s Bach less satisfactory in its approach to sound and rhythm. But his attention to voicing remains exemplary in both of his complete sets, recorded in 1957 and 1975. Another of Milstein’s solo specialties was his own “Paganiniana,” which shows off the ricochet, trills, and sundry other weapons in his technical arsenal. Breathtaking is his Rimsky-Korsakov “Flight of the Bumblebee.” A more lyrical delight is his own arrangement of Liszt’s “Consolation No. 3.” Only one collaboration with Horowitz has been preserved: the Brahms D minor Sonata. Despite recording balance issues, it is an extraordinary performance. *** The Violins of Violinist Nathan Milstein The Ukranian-American virtuoso played four priceless instruments in his career. But one Strad was his favorite, and he renamed it for his wife. The virtuoso violinist Nathan Mironovich Milstein (1903-1992) had a remarkable career by many indicators – his training, his colleagues, his interpretations of works from the Romantic period, and his own life journey from the Ukraine to America during a tumultuous era. Among his many distinctions is the fact he performed in concert up to the age of 82, ending there only because of a debilitating injury to his hand from a fall. So it might make sense that over his long tenure, he was known to play on at least four exceptionally fine violins, three made by Antonio Stradivari and the fourth by Stradivari’s contemporary, Bartolomeo Guarneri. Milstein also had a favorite bow, now known as the “Milstein” Francois Tourte, made in Paris around 1812. But it bears noting that he owned two of the Strads while the third (the 1717 Reiffenberg) and the Guarneri (the 1727 “Milstein Guarneri ‘del Gesu’”) were borrowed. This is increasingly the case with the most prized (and highly valued) violins today in that the musician merely has them on loan from a wealthy collector or an institution that actually owns the instrument. This is sometimes true of very fine stringed instrument bows. This is not an entirely new phenomenon. One prolific collector of Stradivarius and Guarneri violins (as well as fine instruments by other makers) was Rembert Wurlitzer (1904-1963), the heir of the Wurlitzer Co. fortune who separated himself from the musical instrument and jukebox company to buy, authenticate, restore and sell about half of the known 600 Strads in the 1950s. A Wurlitzer certification is highly respected in contemporary authentications. Wurlitzer owned the Reiffenberg violin, although whether that ownership coincided with Milstein playing it is difficult to determine by available records. Milstein’s most prized instrument, the 1716 “Goldman” Strad, was so named as it was owned by collector Henry Goldman, a scion of the family that founded the Goldman Sachs investment banking firm. Milstein considered that his primary instrument through much of his career and renamed it the “Maria Teresa,” to honor both his wife and his daughter who are so named. The Reiffenberg violin is a rarity in that it retains its original label (“Antonius Stradivarius Cremonensis Faciebat Anno 1717”). Labels that say Stradivarius more typically are made by someone else, simply indicating it’s “in the style of” and are of much lower value. It has been owned by Dmitry Sitkovetsky, a Azerbaijan-born classical violinist and conductor, since 1983. Goldman owned the 1716 Strad from 1911-1923, and it changed hands three times before Millstein acquired it in 1945. After Milstein’s death, the family retained ownership until 2006 before selling it to Los Angeles-based businessman Jerry Kohl, a music lover who lends the instrument to players of distinction. **** NATHAN MILSTEIN (1904 - 1992) Milstein, like Elman, Zimbalist, Seidel and Heifetz, was one of the great Russian-Jewish players of the Böhm-Joachim-Auer line. His recollection of studying with Auer highlights once again the master’s insistence upon individuality which Milstein took to heart: ‘If you asked him […] about the playing of a certain passage, he would say, “Go away and think it out for yourself”’. Apart from this he did not accredit much of his success to his teachers, but rather enjoyed the healthy competition of sharing a class with rising stars such as Heifetz, Hansen and Seidel. When the Russian Revolution forced Auer to emigrate Milstein was already well equipped for international prominence. At this time he was engaged by the Ministry of Education to give concerts around Odessa. A few years later he met Vladimir Horowitz and began giving concerts with him in Kiev, Moscow and other cities. Anatoly Lunacharsky, Commissar of Fine Arts and Education, reviewed them under the heading ‘Children of the Soviet Revolution’; this kind of publicity led to many more concerts and a handsome income, which the duo gave to beggars as they had ‘nothing to spend it on’. Because of their potential as ambassadors for Soviet cultural education Milstein and Horowitz were allowed to leave Russia for a European tour. Szigeti advised a demurring Milstein that Europe was agog for such artists as himself and, finding this to be true despite the already-established popularity of his older compatriots, Milstein never returned to Russia. At his US début in 1929 Milstein (under Stokowski) presented Glazunov’s Violin Concerto, which he had played under the composer’s baton at the end of his studentship in Odessa. This secured his ranking in America alongside Elman et al. and he later took US citizenship, renouncing affiliations to Soviet politics and the Communist party. There were certain trademarks to Milstein’s playing. He was utterly attached to his fiddle (even placing it on a chair nearby whilst shaving!) and almost equally obsessed with nurturing his own individualistic style. He held the violin very high without a shoulder-rest and bowed mainly from the shoulder. He employed position changes and vibrato for expressive purposes in the manner of the Germanic pedagogic line to which he belonged, allowing more non-vibrato than most of his contemporaries. Cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, with whom Milstein and Horowitz played trios, claimed that his friend was at his best in unaccompanied repertoire when he did not have to collaborate with another musical personality. There are accounts of tension between Milstein and conductors, although his recorded output includes plenty of concerto performances. Reflecting the stature of an artist as important as Milstein through a small selection of recordings is a tall order: like many of his generation he recorded very widely over a long career and his work is still both famous and highly regarded by performers and listeners. Comparison with Heifetz, not least because of his similar background as one of the many great Auer pupils, is perhaps inevitable. In technical security he is almost Heifetz’s equal and there is a toughness and almost laconic invulnerability to his playing on record that could equally apply to Heifetz. That his performances, such as a fine recording of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra in 1955, sound so normal to our modern ears perhaps demonstrates more than anything else that he belonged to the illustrious band of superstar players who defined this style—a powerful tone with a silvery yet clearly-projected high-register sound, a sonorous and yet slightly metallic G-string colour, and a richly developed vibrato—aspects we still expect to hear from a virtuoso concerto violinist today. This is not to say that Milstein’s playing is not stylistically interesting. His 1951 performance of Brahms’s Double Concerto with Gregor Piatigorsky may refrain from some of the characterful traits of earlier renditions but is nonetheless extremely powerful and virile, whilst his 1949 Glazunov Concerto and, indeed, his 1940 recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto show charisma and depth. The Glazunov is not perfect, with some sharp G-string tuning in the finale, but the bitter-sweet control and avoidance of sentimental excess in the earlier movements complement this romantic yet slightly brittle work to great effect. The 1940 Tchaikovsky selected here is rather better than, for example, his 1953 recording with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Charles Munch (which evidences some slightly scratchy sound in the first movement) and is more flexible in general, even though it studiously avoids the (by then) unfashionable portamento. In chamber repertoire Milstein suffers a little from the ‘big sound’ problem of his generation of concert-hall concerto artists (a branch of the profession that probably reached its zenith in Milstein’s heyday and has become rather less common in recent decades). Thus his Prokofiev Op. 94b Sonata, recorded in 1955 with Artur Balsam, is over-projected and lacks sensitivity, nuance and psychological depth: Milstein sounds oddly ill-at-ease even in this relatively large-scale work. Equally, his many unaccompanied Bach recordings sound over-blown nowadays: his 1956 D minor Chaconne, for example, has all the technical polish one could wish for but is articulated in a style that makes no concession whatsoever to the repertoire, with a steely strength, big tone and hardly any rhythmic nuance, quadruple-stop chords being snatched rather brutally in a manner similar to that of Joseph Fuchs. Milstein’s collaborations with Vladimir Horowitz, however, inject a spark to a number of chamber recordings, and these—including a charismatic and purposeful performance of Brahms’s Violin Sonata, Op. 108 from 1950—are perhaps his most successful. Taken overall, Milstein can be seen as nothing less than one of the great performance phenomena of the twentieth century. . ebay5842 new folder 203